Overview – Issues and debates in psychology

This topic looks at the following issues within psychology:

This topic also looks at the following debates within psychology (and applies them to other areas of the psychology a level course):

- Free will vs. determinism

- Nature vs. nurture

- Holism vs. reductionism

- Nomothetic vs. idiographic approaches

The different approaches in psychology often come down on one side or the other in each of these debates. For example, the humanistic approach believes in free will whereas the biological approach is highly deterministic. These debates also feed into the other issues and options topics that follow.

Gender and culture in psychology

Gender bias

Gender bias within psychology may lead to false conclusions about men and women. This can happen in two directions:

- Alpha bias: When a theory exaggerates differences between genders

- E.g. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory argues that women develop weaker superegos than men and have ‘penis envy‘.

- Beta bias: When a theory ignores differences between genders

- E.g. Early research into the effects of stress in humans characterised the behavioural response as fight or flight. However, this research was based solely on male animals and assumed these behavioural responses were the same across genders. However, later research from Taylor et al (2000) looked at female responses to stress and found their behaviour in response to stress followed a pattern better characterised as tend and befriend than fight or flight.

Beta bias within psychology can lead to androcentrism: A perspective where male psychology and behaviours are viewed as the default and normal. For example, in the stress example above, female tend and befriend behaviours could be viewed as abnormal because they deviate from typical male (fight or flight) behaviours. However, such behaviours are only abnormal from an androcentric perspective – when studies take account of differences between genders the tend and befriend behaviours are seen as normal.

AO3 evaluation points: Gender bias

Gender bias can occur for a variety of reasons.

For example, researchers may have pre-conceived gender stereotypes that affect how they treat participants, resulting in investigator effects.

Further, publication bias could cause alpha bias. If a study finds no differences between genders then this may be seen as less psychologically interesting than a study that finds a big difference between genders, making studies that find differences between genders more likely to get published. This results in a publication bias towards studies that emphasise differences between genders.

Cultural bias

Berry (1969) distinguishes between emic and etic research:

- Emic: Researching a culture from within to understand that culture specifically (and not applying the findings to other cultures).

- Etic: Conducting research from an outside perspective to discover universal truths about human psychology (i.e. applying the findings to all people in all cultures).

An imposed etic is an example of cultural bias and can lead to ethnocentrism: A perspective where the behaviours of a certain ethnicity or culture are seen as the default and normal. As such, any behaviour that deviates from the norms of that culture may be seen as abnormal.

For example, Ainsworth’s studies of infant attachment only looked at American infants and concluded that secure attachment styles are most psychologically healthy. From this perspective, child-rearing practices in other countries may be seen as unhealthy or abnormal rather than simply different. For example, the American perspective might see German parents as cold and rejecting. But from the German perspective, American parents may seem overly coddling, preventing the child from becoming independent.

AO3 evaluation points: Cultural bias

Etic research is not automatically bad. The point of much of psychology is to uncover universal (nomothetic) laws of human behaviour. And given that all humans in all cultures have very similar biology, there are likely to be many universal psychological truths. But if researchers assume their culture is the default (imposed etic), that’s where the bias comes in.

Psychological research can avoid cultural bias by being conscious of cultural relativism, i.e. differences between cultures.

Ethical issues

Psychological studies often face ethical issues. Ethical issues in the design of the study itself are covered in the research methods section. However, a psychological study and its findings may have ethical implications that go beyond the participants directly involved to affect society more generally – particularly if the research is socially sensitive.

Socially sensitive research

Socially sensitive research is research that has ethical implications for people beyond the researchers and participants directly involved. Examples of this include:

- Social groups: Research into certain groups (e.g. ethnic, religious, gender, sexual orientation) may have negative consequences for those groups.

- E.g. A study that found differences in skills between genders could bias company hiring practices.

- The participants’ friends and families: Research can have consequences for people related to participants in a study.

- E.g. A participant in a study finds out they have genes associated with depression, which may lead their children to wonder if they have inherited the depression genes.

- The researchers’ institution: Some studies can bring negative attention to the researchers’ institution.

- E.g. A study into differences between ethnic groups may attract negative attention towards the institution it was conducted from the media and civil rights groups.

Sieber and Stanley (1988) outlines various ethical concerns that researchers should consider before conducting socially sensitive research. These include:

- Implications: What harmful effects could the study have on society? For example, could it be used to legitimise discrimination (e.g. Raine)?

- Public policy: Psychological studies could be used by governments to support or inform policies (e.g. Burt (1955)).

- Validity: Are the study’s results accurate? There are many cases where research findings have turned out to be inaccurate or fraudulent (e.g. Burt (1955)).

Researchers must weigh up these concerns against the potential benefits. In some cases, psychologists argue that even if a study causes harm it should still be conducted because the knowledge gained is so valuable (e.g. Milgram).

The following are examples of socially sensitive research studies and ethical implications:

| Study | Description | Ethical implications |

| Burt (1955) | Research supporting a genetic basis of intelligence. | Burt’s research led to the 11+ exam in the UK, which tested for ‘natural’ intelligence. This exam would determine whether a child went to grammar school or not, which greatly affected the child’s life opportunities. Later, it emerged that some data in Burt’s study was made up, but the 11+ exam remained. |

| Raine (1996) and Raine et al (1997) | Brain scans suggesting antisocial, violent, and murderous people have particular brain structures. | Raine suggested brain scans in childhood could be used to identify potentially violent criminals of the future. This policy, if enacted, could potentially reduce crime but would also likely lead to discrimination against people with these brain structures. |

| Milgram’s experiments | Research into the effects of authority on obedience. | Milgram’s experiments deceived participants and caused psychological distress. Although this may be seen as unethical, some argue that the value of the knowledge resulting from these experiments outweighs the harm done to the participants. |

AO3 evaluation points: Socially sensitive research

- Ethical concerns: Some argue that socially sensitive research shouldn’t be carried out because of ethical concerns.

- May increase discrimination: Socially sensitive research findings may be used to justify discrimination and prejudice. For example, the 1909 Asexualisation Act in California allowed for the sterilisation of people on the basis of psychological traits such as low intelligence or mental illness.

- May reduce discrimination: On the other hand, Scarr (1988) argues that research into differences between groups (e.g. genders, races, sexual orientations) may lead to greater understanding, which could lead to changes that reduce discrimination and improve the lives of disadvantaged groups.

Free will vs. determinism

Free will

There are differing opinions within psychology on the question of whether humans have free will – i.e., whether humans are able to freely choose their behaviours. The opposite of free will is determinism, which says that human behaviours are caused by physical processes and that these physical processes cannot be overruled.

Humanistic psychology, for example, believes humans do have free will. While physical factors – e.g. genetics and environment – influence our behaviours, humanistic psychologists believe humans are able to transcend these physical factors and make free choices.

Determinism

Determinism is the rejection of free will. There are various different forms of determinism, including:

Hard vs. soft determinism

- Hard determinism: Human behaviour is entirely caused by physical processes that are beyond our control. So, free choices are impossible.

- Soft determinism: Human behaviour is largely determined by physical processes (e.g. biology, upbringing, etc.) but humans are able to overrule these processes and exert their free will in some circumstances.

Biological determinism

Biological determinism (i.e. the biological approach) is the view that behaviours are determined by biological processes. Examples of such biological processes include:

- Genetics: Many psychological disorders and behaviours (e.g. schizophrenia, OCD, anorexia, and alcohol addiction) seem to have a strong genetic component as evidenced by twin studies.

- Hormones: Increasing levels of the hormone testosterone, for example, make people behave more aggressively and vice versa.

- Biological structures: Brain scans show that people with OCD often have increased activity in the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

- Physiological processes: The autonomic nervous system has a big influence on behaviour (e.g. increased heart rate before a date makes you behave like a nervous wreck) but is not under conscious control.

Environmental determinism

Environmental determinism (i.e. the behaviourist approach) is the view that behaviours are determined by conditioning from our environment. Examples of such conditioning include:

- Positive reinforcements: E.g. getting given sweets as a child in exchange for good behaviour, getting a pay rise at work for putting in long hours.

- Punishment: E.g. getting told off by your parents for fighting with your brother, getting told off by your boss for being late for work.

Psychic determinism

Psychic determinism (i.e. the psychodynamic approach) is the view that behaviours are governed by unconscious desires and conflicts. Examples include:

- Freud would say an unresolved oedipus complex in childhood can cause aggressive behaviour as an adult man.

- Freudian slips – e.g. calling your girlfriend ‘Mum’ – are not simply accidents, but expressions of the unconscious mind.

AO3 evaluation points: Free will vs. determinism

Strengths of free will/weaknesses of determinism:

- Consistent with our moral intuitions and the legal system: If determinism is correct, then there is a sense in which people are not morally responsible for their actions (because they are not freely chosen). As such, it would seem unfair to blame people or hold them responsible for something they couldn’t help doing.

- Subjective validity: Our experience tells us we do have free will. For example, it feels like we are making a free choice when we pick food from a menu at a restaurant or pick what clothes to wear.

Weaknesses of free will/strengths of determinism:

- Evidence against free will: Some neuroscientific experiments suggest humans do not have free will. For example, Soon et al (2008) used brain scans to measure brain activity as participants made a decision to press a button with either their left or right hand. The brain scans showed activity in the prefrontal and parietal cortices (areas associated with decision making) up to 10 seconds before the participants were consciously aware of their decision.

- Impossible to prove: Free will is in some sense non-physical (because if we could identify the physical cause of free will then it would not be free will at all but determinism!). However, non-physical things are difficult/impossible to measure and quantify.

Soft determinism could represent an in-between approach to the free will vs. determinism debate. For example, Bandura’s social learning theory has elements of both: Although we often imitate the behaviours of our environment (environmental determinism), one could argue that mediating processes (e.g. attention and motivation) represent an opportunity for free will to play a part. In other words, we can choose which behaviours we pay attention to and choose to reflect on whether we are motivated to reproduce them and why.

Nature vs. nurture

The nature vs. nurture debate is about how much our behaviour is determined by genetics/biology and how much is determined by environment.

Nature (heredity)

At one extreme, nativists believe our behaviour is pre-determined by nature. Nativists believe our behaviour is explained by heredity – i.e. inherited biological characteristics such as genetics.

Twin studies provide a way to assess the heritability of behaviour. Monozygotic twins have identical genetics and so, if nativism was 100% correct, you would expect them to behave identically too. However, monozygotic twins often have different personalities and preferences, suggesting environment plays a role in behaviour too.

The heritability coefficient is a way to quantify the extent to which a characteristic is determined by genetics. A heritability coefficient of 1 means the characteristic is 100% genetic, whereas 0 means the characteristic has nothing to do with genetics. The following are examples of studies to determine the heritability coefficient of various psychological traits and disorders:

| Trait | Heritability coefficient |

Studies |

| Intelligence (IQ) | 0.8 | Bouchard (2013) |

| Schizophrenia | 0.79 | Hilker et al (2018) |

| OCD | 0.45 – 0.65 | Grootheest et al (2005) |

The biological approach to psychology can be said to support the nature side of the debate. For example, the studies above suggest genetics play an important role in various behaviours and psychological traits.

Nurture (environment)

At the other extreme, empiricists believe humans are born as blank slates with no innate nature. So, because humans don’t come with any pre-programmed traits or nature, any behaviour must be learned from the environment.

The learning approach to psychology leans towards the nurture side of the debate. Skinner, for example, explained behaviours as a result of operant conditioning and so different conditioning leads to different behaviour (regardless of genetics). For example, if someone who learned to do their homework because of positive reinforcement did not receive that positive reinforcement, then they would have behaved differently (i.e. not done their homework).

Interactionism

The interactionist approach lies somewhere between the two: Our genetic nature predisposes us towards some behaviours more than others, but how these genes are expressed is often dependent on environment. This goes back to the difference between genotype and phenotype.

There are several examples of this elsewhere in the course. For example, OCD has a strong genetic component but not everyone with these genes goes on to develop OCD. For example, some people may take drugs that suppress OCD symptoms, others may overcome OCD with cognitive behavioural therapy, and some people with a genetic disposition towards OCD may simply never experience events that trigger OCD symptoms. And although twin studies support the existence of a genetic component to OCD, the heritability coefficient is less than 0.7; there are many instances where just one twin develops OCD but not the other.

One mechanism through which environment interacts with genetics is epigenetics. Lifestyle choices (e.g. smoking) and environmental effects (e.g. living in an area with air pollution) ‘switch on’ certain genes and ‘switch off’ others. Although epigenetic effects do not alter a person’s DNA sequence itself, there is some evidence they can alter the genes they pass on to their children.

AO3 evaluation points: Nature vs. nurture

Realistically, psychologists on both sides of the nature vs. nurture debate are interactionists – it’s clear that both genetics and environment have effects on behaviour. The debate, then, is to what extent nature determines behaviour and to what extent nurture does.

Strengths of nativism/weaknesses of empiricism:

- Supported by evidence: Twin studies, sibling studies, and gene mapping suggest genetics play an important role in various psychological traits and disorders (such as those outlined in the table above).

Weaknesses of nativism/strengths of empiricism:

- Conflicting evidence: There is also strong evidence that behaviour can be learned and changed through conditioning. For example, Bandura’s Bobo the doll experiment shows how children may learn aggressive behaviours in response to their environment.

- Confounding variables: Many sibling and non-identical twin studies assume the environments of siblings and twins are exactly the same because they share the same parents, household, etc., which leads the researchers to conclude any differences in behaviour are due to genetics. However, there are many reasons why the environment may differ between siblings and thus exert an effect on behaviour. For example:

- Siblings who experience the same life event (e.g. parental divorce) will experience it at different ages.

- Parents and teachers may accidentally treat non-identical twins differently due to their differing appearances.

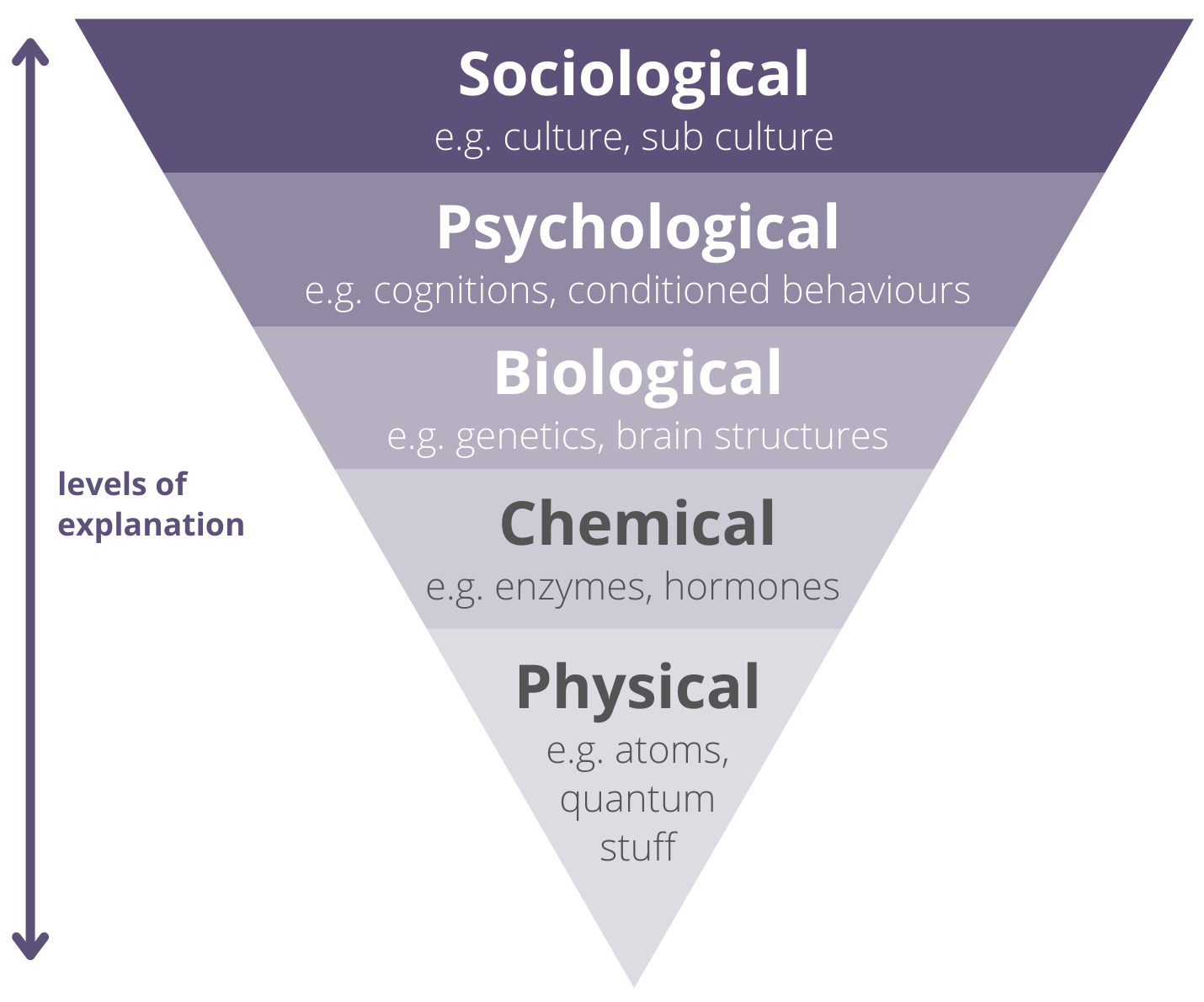

Reductionism vs. holism

The holism vs. reductionism debate is about levels of explanation: Whether psychology should seek to understand a person’s behaviour as a whole or whether behaviours can be broken down and explained in terms of smaller parts.

The same phenomena can be explained at different levels. For example, the phenomena of depression:

- Depression can be explained at a psychological level, such as sustained negative thoughts and low mood.

- But these thoughts and emotions can also be explained biologically, by referring to things like neurons firing and neurotransmitters binding to receptors (e.g. low serotonin).

- Explanatory levels can go even lower, though, such as by breaking down your description of neurons and neurotransmitters into basic physical components such as atoms.

Holism sees multiple levels of explanation as valuable whereas reductionism thinks psychological phenomena can be entirely explained (without losing any valuable details) using just one of these levels of explanation.

Reductionism

Extreme reductionist explanations break behaviours down into a single cause. An example of a reductionist explanation would be something like: Depression is caused by low serotonin.

The biological approach to psychology leans heavily towards reductionism (biological reductionism). For example, a proponent of this approach might argue that behaviour can be explained entirely in terms of physical/biological causes without reference to higher levels of explanation, such as a person’s upbringing or cognitions.

Similarly, the behaviourist approach can be reductionist (environmental reductionism). For example, an extreme behaviourist might explain behaviour solely in terms of conditioning without reference to lower levels of explanation such as the underlying biology.

Holism

Holistic approaches look at the person as a whole to explain their behaviour. For example, a holistic explanation of depression will consider the person’s genetics and biology but also their experiences, upbringing, and the general social context and culture in which they live. Advocates of holism believe human behaviour is too complex to be fully explained from one level of explanation and that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”.

The humanistic approach is arguably the most holistic approach to psychology. It treats every person as a unique individual that cannot be reduced to general explanations. The humanistic approach to psychological treatment is similarly holistic: It seeks to address and improve all aspects of the person.

AO3 evaluation points: Holism vs. reductionism

Again, you don’t have to dogmatically come down on either the reductionist or the holism side but can instead opt for an in-between approach. For example, you could argue that in some situations several levels of explanation are best and in others a single level is best. You could argue there is no one-size-fits-all answer as both holism and reductionism are useful for different things.

Strengths of reductionism/weaknesses of holism:

- More scientific: Reducing variables and behaviour enables psychological studies to be conducted in a scientific – i.e. repeatable, quantifiable, and objective – way. For example, reducing schizophrenia to dopamine activity enables researchers to objectively determine whether someone has schizophrenia and reliably measure whether a treatment is effective or not. In contrast, a holistic approach would make it more difficult to objectively determine whether or not someone has schizophrenia, as it would need to account for subjective experiences and other factors in addition to dopamine levels.

- Practical applications: Reductive approaches have led to effective treatments. For example, biological reductionism has led to the creation of effective treatments for depression (e.g. SSRIs) and effective treatments for schizophrenia (e.g. antipsychotics).

Weaknesses of reductionism/strengths of holism:

- Overly simplistic: Reductionism may overly simplify behaviour and miss out important details, whereas holism takes account of the full range and context of behaviours. For example, the schizophrenia/dopamine example above is overly simplistic and would not be suitable as a valid diagnostic method by itself. Another example illustrating the limits of reductionism is the Stanford prison experiment, which could only be understood with reference to the whole situation – particularly the interactions between the individuals. A reductionist approach of only looking at a prison guard’s biology, for example, would miss the wider context of how the social role he was playing fed into that biological state.

Nomothetic vs. idiographic

The nomothetic vs. idiographic debate is about whether the best approach to psychology is to look at similarities between humans or the differences that make them unique.

Nomothetic approach

The nomothetic approach (‘nomos’ = ‘law’) to psychology seeks to identify general laws of human behaviour by looking at similarities between people and groups of people.

Classifications are a form of nomothetic generalisation. For example, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders provides ways to categorise people as having mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, personality disorders, etc. Similarly, several nomothetic ways to categorise personality types exist such as the five-factor model of personality, the Myers-Briggs type indicator, and astrological star signs.

Principles are another form of nomothetic generalisation. For example, behaviourism describes general laws through which behaviours are conditioned, such as operant and classical conditioning. Similarly, cognitive approaches try to develop theoretical models that explain human behaviour.

Characteristics of the nomothetic approach:

- Derives general laws by looking at similarities between multiple people

- Emphasis on quantitative over qualitative data

- Prefers experiments with large sample sizes rather than individual case studies

- The behaviourist, cognitive, and biological approaches are all highly nomothetic: They want to identify general laws

- More objective, less subjective

Idiographic approach

The idiographic approach (‘idios’ = ‘distinct self’) seeks to understand the individual as a unique being without comparing them to others. The idiographic approach believes that the uniqueness of each person means it is difficult/impossible to identify general laws that apply across populations.

Characteristics of the idiographic approach:

- Looks at individuals as unique cases and describes them

- Emphasis on qualitative over quantitative data

- Prefers individual case studies and self-report methods over large-scale experiments

- Most strongly associated with the humanistic approach to psychology and to a lesser extent psychodynamic approaches

- More subjective, less objective

AO3 evaluation points: Idiographic vs. nomothetic

Again, as always, you can take an in-between approach between idiographic and nomothetic. For example, you can start with a nomothetic approach and identify general laws – as long as you recognise that these general laws do not apply to everyone. Once the general laws are established, you can take a more idiographic approach and study the unique ways people deviate from these laws.

Strengths of nomothetic approach/weaknesses of idiographic approach:

- More scientific: Science is all about what can be objectively measured and repeated. By using these tools, the nomothetic approach is able to identify general scientific laws of human behaviour (similar to how physics identifies the general scientific laws that govern physical matter). These psychological laws have predictive power. For example, Milgram’s experiments tell you how likely someone is to obey an authority figure.

- Practical applications: Identifying nomothetic laws of human behaviour is likely to have useful practical applications. For example:

- Insights from Zimbardo’s prison study into how humans behave when in certain social roles could inform policies in prisons to reduce abuse.

- Identifying similarities in brain chemistry across individuals with depression could yield new treatments that treat depression by addressing this brain chemistry.

- Identifying common thought patterns among gambling addicts could lead to cognitive therapies that target these thought patterns and reduce gambling addiction.

Weaknesses of nomothetic approach/strengths of idiographic approach:

- Exceptions: Although the nomothetic approach is able to identify general laws, these laws do not apply universally to every human. For example, operant conditioning may explain why some people get addicted to cigarettes, but another person may smoke the same amount and not get addicted. Exceptions like this highlight the limitations of the nomothetic approach. In contrast, the idiographic approach is able to account for these deviations from the general laws because it treats the individual as unique.

- Missing detail: The nomothetic approach is likely to miss important or interesting details about the people studied. In contrast, the idiographic approach produces rich data that gives a complete account of the individual studied (e.g. Freud’s case studies).

Relationships>>>

or:

Gender>>>

or: