Overview – Addiction

Addiction is a psychological disorder characterised by an inability to stop engaging in certain behaviours or consuming certain substances despite negative consequences. A Level psychology looks at the following aspects of addiction:

- Describing addiction (including dependence, tolerance, and withdrawal)

- Risk factors for developing addiction (including genetic vulnerability, stress, personality, family and peer influence)

- Explanations of nicotine addiction (including neurochemistry and learning theory)

- Explanations of gambling addiction (including learning theory and cognitive explanations)

- Ways to reduce addiction (including drug therapy, behavioural interventions, cognitive behavioural therapy, and the application of the theories of planned behaviour and Prochaska’s six-stage model)

Describing addiction

The three main symptoms that describe addiction are:

These symptoms differ depending on whether the addiction is to a substance (e.g. nicotine) or behaviour (e.g. gambling).

Dependence

Dependence can be physical and/or psychological:

- Physical dependence: When someone experiences withdrawal symptoms (e.g. pain, shaking, seizures) when they stop using the substance.

- Psychological dependence: When someone has a strong desire to use the substance.

For example, a person with alcohol addiction may experience withdrawal symptoms upon stopping drinking (physical dependence). But even after these withdrawal symptoms have passed and the person is no longer physically dependent on alcohol, they may have urges to drink alcohol that persist for much longer (psychological dependence).

Tolerance

Tolerance is when a person’s response to a drug reduces such that they need higher and higher doses to achieve the same effect.

Tolerance occurs because the body adjusts to use of the drug in order to maintain homeostasis (feeling and functioning normally). For example, drinking alcohol disrupts the brain’s normal functioning and so the brain reacts to bring things back to normal and achieve homeostasis. This creates a new ‘normal’ and so the person then has to drink more next time in order to get the same buzz as before.

Tolerance occurs because the body adjusts to use of the drug in order to maintain homeostasis (feeling and functioning normally). For example, drinking alcohol disrupts the brain’s normal functioning and so the brain reacts to bring things back to normal and achieve homeostasis. This creates a new ‘normal’ and so the person then has to drink more next time in order to get the same buzz as before.

Tolerance to one drug often creates increased tolerance to other drugs. For example, smoking cigarettes (nicotine) increases tolerance to caffeine because caffeine and nicotine have similar effects in the body. This is known as cross-tolerance.

Withdrawal syndrome

Withdrawal syndrome is when a person develops unpleasant symptoms upon stopping or reducing drug use. These may include pain, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and shaking.

Withdrawal symptoms are often the opposite of the ones created by the drug. For example, a person addicted to painkillers may experience severe pain when they stop using the painkillers. The unpleasantness of withdrawal symptoms creates a motivation to continue using the drug: Taking the drug reduces withdrawal symptoms.

The extent of withdrawal syndrome depends on which drug the person is addicted to (e.g. heroin withdrawal is typically more severe then nicotine), how much they use (typically, the greater quantity of drugs a person uses, the worse the withdrawal), and how frequently they use it (e.g. regular use at the same time of day will typically cause worse withdrawal than sporadic use).

Risk factors for addiction

Risk factors are things that increase the likelihood of addiction. These include:

Genetic vulnerability

Evidence suggests there is a genetic component to addiction. For example:

- Nielsen et al (2008) compared DNA of 104 former heroin addicts with 101 controls and found several genetic patterns associated with heroin addiction.

- A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies by Verhulst et al (2015) estimated that alcohol addiction is approximately 50% heritable.

- Twin studies: Concordance rates of alcohol and heroin addiction are much higher among identical twins than non-identical twins.

However, it’s impossible for addiction to be 100% genetic. A person with a genetic predisposition towards heroin addiction, for example, can’t become addicted to heroin if they never encounter the drug in the first place. So, genetic vulnerability must interact with environment to cause addiction.

AO3 evaluation points: Genetic vulnerability to addiction

Strengths of genetics as a risk factor for addiction:

- Evidence supporting genetic component of addiction: See studies above.

Weaknesses of genetics as a risk factor for addiction:

- Interactionism: Despite this genetic component, there is clearly more to addiction than just genetics. Firstly, a person may live in an environment where they never come across addictive substances and so their genetic vulnerability never materialises as actual addiction. Secondly, even identical twins don’t have 100% concordance rates for addiction. As such, the role of genetics in addiction should be understood from an interactionist perspective: Genetic vulnerability + environment = addiction.

- Variation between substances: Evidence suggests genetic vulnerability to addiction varies between different substances/behaviours. For example, a person may have genetics that make them particularly vulnerable to developing gambling addiction but not alcohol addiction.

- Usual methodological issues with twin studies: Twin studies typically assume that both identical (monozygotic) and non-identical (dizygotic) are raised in identical environments and so any differences in concordance rates are due to genetics. However, this assumption is not certain. For example, parents are likely to treat non-identical twins more differently than identical twins and so this environmental factor could also contribute to differences in concordance rates. This could mean genetic influences on addiction are exaggerated.

Stress

Stress is a risk factor for addiction – both in the short term and historically.

In the short term, a person may turn to addictive substances as a way of coping with stress. For example, a person may turn to alcohol after a stressful day at work. Over time, this may become a regular habit and eventually result in an addiction to alcohol.

In the short term, a person may turn to addictive substances as a way of coping with stress. For example, a person may turn to alcohol after a stressful day at work. Over time, this may become a regular habit and eventually result in an addiction to alcohol.

However, mediating factors may reduce the risk of addiction in response to stress. For example, if a person is under a high amount of stress but has a strong support network, this may improve their ability to cope with the stress and reduce the risk of addiction.

Further, historical stress – particularly during childhood – is also a risk factor for addiction. For example, Andersen and Teicher (2009) describe how stress during childhood and adolescence (a ‘sensitive period’) affects brain development, making a person more vulnerable to addiction in adulthood. Another example is Epstein et al (1998), who found that sexual abuse in childhood meant women were twice as likely to develop alcohol addiction as adults.

AO3 evaluation points: Stress as a risk factor for addiction

Strengths of stress as a risk factor for addiction:

- Face plausibility: It’s easy to understand how acute stress could lead to addiction. Stress is an unpleasant feeling and addictive substances (e.g. alcohol, cigarettes, drugs) alleviate this feeling.

- Evidence supporting the role of stress as a risk factor for addiction: Several studies have demonstrated a correlation between stress and addiction. For example, Tavolacci et al (2013) assessed stress levels of French students using a questionnaire and found that stressed students were more likely to smoke, abuse alcohol, or develop cyberaddiction.

- Practical applications: Understanding the link between stress and addiction can be used to reduce addiction and relapse rates. For example, doctors could measure stress levels and direct at-risk patients towards resources that help them cope with stress and reduce their risk of addiction.

Weaknesses of stress as a risk factor for addiction:

- Correlation vs. causation: Although stress and addiction are correlated, this does not automatically prove stress causes addiction. Being addicted is itself a stressful situation and so the direction of causation could go the other way: Addiction may cause stress (rather than stress causing addiction).

- Other factors: Although stress appears to be a risk factor for addiction, it is not the only one. The various risk factors – genetics, personality, family and peer influence – all combine to cause (or reduce the risk of) addiction.

Personality

Certain personality traits appear to be risk factors for developing addiction – although whether there is such a thing as an ‘addictive personality’ is disputed by many psychologists.

Eysenck (1997) argues that certain personality types – such as people high in neuroticism (a tendency towards negative feelings) and psychoticism (a tendency towards aggression and impulsivity) – are more prone to addiction. According to this theory, the needs of these personality types make them more prone to addiction. For example, drugs may alleviate the negative feelings of a neurotic personality type, making them more likely to get addicted.

Another theory linking personality and addiction is Cloninger’s (1987) tri-dimensional theory. According to this theory, there are three key personality traits: Response to danger, novelty seeking, and reward dependence. Using this framework, Cloninger argues that addicts typically display the following patterns:

- High novelty seeking: People who seek new experiences and sensations are more likely to seek out and become addicted to drugs.

- High reward dependence: People who learn quickly from rewarding stimuli (i.e. the pleasant sensations of drugs) will become addicted to rewards from drugs more quickly, making them more likely to become addicts.

- Low response to danger: People who are less worried about the dangers of drugs are more likely to try them and become addicted.

AO3 evaluation points: Personality as a risk factor for addiction

Strengths of personality as a risk factor for addiction:

- Supporting evidence: Some studies support a connection between personality traits and addiction. For example, a meta-analysis by Howard et al (1997) found high novelty seeking was correlated with increased risk of alcohol abuse in teenagers and young adults – just as Cloninger’s tri-dimensional theory predicts.

Weaknesses of personality as a risk factor for addiction:

- Conflicting evidence for the role of personality in addiction: However, the same meta-analysis by Howard et al (1997) described above found evidence for a link between the other two traits (high reward dependence and low response to danger) and alcohol abuse was much less consistent.

- Correlation vs causation: Although there is evidence that personality traits are correlated with addiction, this does not automatically mean that having those personality traits causes one to be at greater risk of addiction. It could be that being addicted to drugs changes one’s personality (and so the direction of causation goes the other way).

- Other factors: Although personality appears to be a risk factor for addiction, it is not the only one. The various risk factors – genetics, stress, family and peer influence – all combine to cause (or reduce the risk of) addiction.

Family influence

Family influence is another risk factor for addiction. It can be explained in several ways.

According to social learning theory, people learn and imitate behaviours of role models they identify with. Assuming this theory is correct, it would go a long way to explaining addiction. For example, a child may identify with their cigarette-smoking father (role model) and observe the reward (pleasure/stress relief) he gets from smoking. This provides vicarious reinforcement of cigarette-smoking behaviour, which makes the child more likely to try cigarettes and become addicted.

Another explanation of family influence on addiction is perceived parental approval. If a child perceives that their parents have a positive (or at least neutral) attitude towards a drug, this makes them more likely to try and become addicted to that drug. For example, Livingston et al (2010) found that children whose parents allowed them to drink alcohol in their final year of high school were more likely to drink heavily the next year at college.

AO3 evaluation points: Family influence as a risk factor for addiction

Strengths of family influence as a risk factor for addiction:

- Evidence supporting the role of family influence in addiction: Several studies support the role of family influence on addiction, such as Livingston et al (2010) described above. Another example is Akers and Lee (1996), who looked at smoking behaviours of 454 adolescents over a 5 year period. The researchers found that family influence (via social learning theory) made the children more likely to start and continue smoking cigarettes.

Weaknesses of family influence as a risk factor for addiction:

- Variations in family influence: Various factors, such as the age of the child and the extent to which they identify with the family member, influence the strength of family influence on addiction. For example, seeing a parent smoke at age 12 may be a greater risk factor for cigarette addiction than at age 4, when the child doesn’t understand what is going on. Similarly, if the child’s father smokes but the child identifies more with the mother, this reduces the strength of family influence.

- Other factors: Although family influence appears to be a risk factor for addiction, it is not the only one. The various risk factors – genetics, stress, personality, peer influence – all combine to cause (or reduce the risk of) addiction. Another factor that is relevant to social learning theory explanations is mediating processes, which are cognitive processes where a person decides whether to imitate a behaviour or not. For example, mediating processes may mean a child observes their parents smoking but decides not to imitate that behaviour.

Peer influence

Like family, peer influence may also increase the likelihood that a person develops an addiction.

For example, if a person’s friendship group all starts smoking cigarettes, it makes that person more likely to try smoking and become addicted to cigarettes. Their friends may offer them cigarettes, or the person may feel left out if all their friends are smoking and they’re not.

Again, social learning theory can be applied here: If someone identifies with their friend, sees them smoke cigarettes and be rewarded for that behaviour (e.g. others think it’s cool), this provides vicarious reinforcement of that behaviour, making them more likely to imitate it.

AO3 evaluation points: Peer influence as a risk factor for addiction

Strengths of peer influence as a risk factor for addiction:

- Evidence supporting the role of peer influence in addiction: Several studies have found correlations between addiction and having friends who are addicts. The hypothesis that having peers who use drugs will increase the likelihood that a person becomes addicted to drugs also has face plausibility: It just seems common sense.

Weaknesses of peer influence as a risk factor for addiction:

- Possibility that peer influence on addiction is exaggerated: Despite the face validity of peer influence on addiction, its influence may be exaggerated. For example, a review by Bauman and Ennett (1996) found that many studies cite peer influence as a reason for substance abuse without actually testing this claim against evidence.

- Correlation vs. causation: Even if addiction and certain peer groups are correlated, it is difficult to prove which comes first. It may be the case that having peers who use drugs increases the likelihood that that person also uses and becomes addicted to drugs. But it may also be the case that people who use drugs seek out peers who also share an addiction to that drug. For example, a person with an alcohol addiction may seek out friends who like going to pubs and drinking a lot of alcohol as this enables them to indulge their addiction.

- Variations in peer influence: Like with family, different factors – e.g. age and the extent to which a person identifies with their peer – influence the strength of peer influence. For example, a 40 year old would probably be less influenced by friends who smoke cigarettes than they would as a teenager.

- Other factors: Although peer influence appears to be a risk factor for addiction, it is not the only one. It is difficult to determine the relative strength of the various risk factors – genetics, stress, personality, family influence – on addiction. There are also other factors not listed on the syllabus, such as influence from the media (e.g. films and music) and advertising.

Explanations of nicotine addiction

Nicotine is a highly addictive substance found in cigarettes. The syllabus lists two explanations of nicotine addiction: Neurochemistry (the dopamine desensitisation hypothesis) and learning theory explanations.

Nicotine is a highly addictive substance found in cigarettes. The syllabus lists two explanations of nicotine addiction: Neurochemistry (the dopamine desensitisation hypothesis) and learning theory explanations.

Neurochemistry

Nicotine addiction can be explained via neurochemistry. In particular, nicotine manipulates the brain’s reward system via the neurotransmitter dopamine. A summary of this process (the dopamine desensitisation hypothesis) is as follows:

- Neurons in the brain have nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)

- Nicotine binds to these nAChRs receptors, which causes dopamine release (in particular from the ventral tegmental area of the brain)

- Dopamine activity (particularly in the nucleus accumbens and frontal cortex) creates a pleasurable feeling of mild euphoria, stress relief, and increased alertness

- This pleasurable feeling becomes associated with nicotine intake

- nAChRs receptors shut down and no longer respond to nicotine (the receptors are downregulated: They become desensitised to nicotine)

- This increases tolerance: More nicotine is needed to achieve the same effect

This stimulation of the dopamine system is known as the common reward pathway.

Further neurochemical explanation of nicotine addiction can be found in the nicotine regulation model. According to this model, prolonged periods without nicotine causes nAChRs receptors to become resensitised to nicotine (upregulation). This state of having many nAChRs receptors that are available but not stimulated causes withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety. Smoking alleviates these withdrawal symptoms and reinforces the behaviour.

The nicotine regulation model explains why smokers find the first cigarette of the day to be the most satisfying: During sleep, nAChRs receptors are upregulated and become more sensitive, resulting in a greater dopamine release when smoking resumes.

AO3 evaluation points: Neurochemical explanations of nicotine addiction

Strengths of neurochemical explanations of gambling addiction:

- Evidence supporting the dopamine desensitisation hypothesis: Several studies have found nicotine causes dopamine release. For example, table 3 of Sharma and Brody (2009) summarises several brain scan studies that show increases in dopamine activity following nicotine administration.

Weaknesses of neurochemical explanations of gambling addiction:

- Methodological concerns: However, many studies linking nicotine and dopamine were conducted on animals rather than humans. As such, the findings may not be valid when applied to the human dopamine response to nicotine.

- Other factors: Although dopamine almost certainly plays a role in nicotine addiction, it’s likely that other neurochemical factors are at play. For example, nicotine also triggers the release of endogenous opioids, which also have pleasurable effects in the body. This suggests that the dopamine desensitisation hypothesis is an incomplete explanation of nicotine addiction.

Learning theory explanations

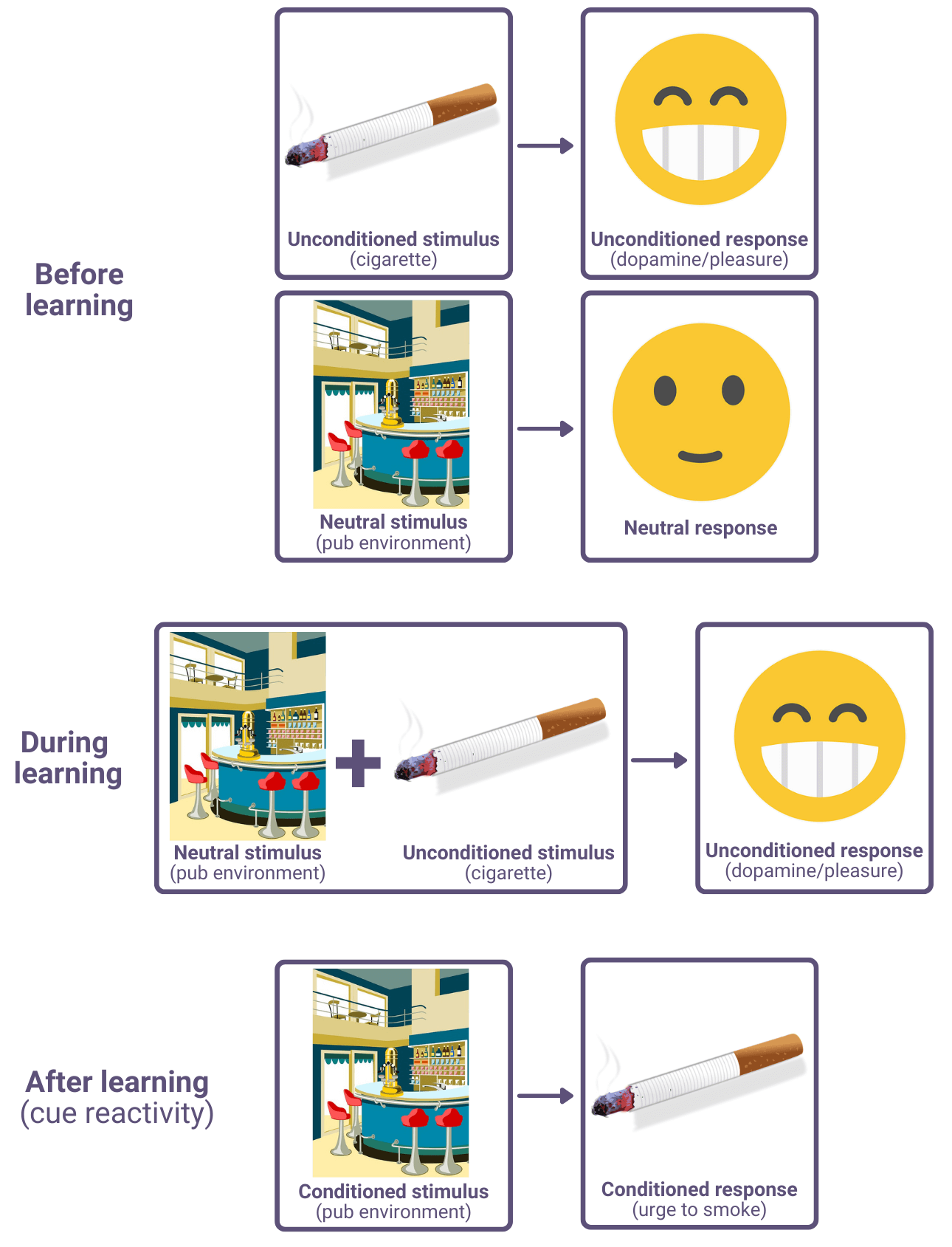

Learning theory explains nicotine addiction as learned behaviour in response to environmental stimuli.

One way learning theory can explain nicotine addiction is via operant conditioning. Smoking behaviour is reinforced both positively and negatively:

- Positive reinforcement: Smoking causes pleasant feelings of mild euphoria and stress relief. This reward makes the person more likely to smoke again.

- Negative reinforcement: Stopping smoking causes unpleasant withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety, low mood, and difficulty sleeping. The person is thus more likely to smoke again in order to avoid these unpleasant feelings.

The pleasant sensations of smoking can also become associated with cues in the environment via classical conditioning. For example, if a person regularly smokes cigarettes when they’re in a pub, then they may condition themself to associate pubs with smoking. Once this association is learned, going to the pub may trigger an urge to smoke cigarettes. This is known as cue reactivity.

Learning theory explanations of nicotine addiction may also include social learning, such as the peer pressure example described above.

AO3 evaluation points: Learning theory explanations of nicotine addiction

Strengths of learning theory explanations of nicotine addiction:

- Evidence supporting learning theory explanations: Studies provide support for various learning theory explanations of nicotine addiction. For example:

- Operant conditioning: Over a series of 24×45 minute sessions, Levin et al (2010) gave rats two waterspouts to drink from: One normal and one that administered nicotine. As the sessions progressed, the rats increasingly drank from the nicotine waterspout, which suggests this behaviour was conditioned via positively reinforcement.

- Cue reactivity (classical conditioning): A meta-analysis by Carter and Tiffany (1999) found cigarette addicts reported higher cravings to smoke and demonstrated physiological responses associated with cravings (e.g. increased heart rate) when exposed to smoking-related cues.

- Social learning theory: A report by the US Office of the Surgeon General (2012) reviewed multiple studies, many of which support the social learning explanation of nicotine addiction. The section concludes: “the evidence is suggestive of a […] causal role for peer group influences.”

- More complete explanation: Neurochemical explanations (and operant conditioning) explain why people continue to smoke, but not why they start smoking in the first place. However, social learning theory explains this first stage: People are motivated to try smoking from observing the rewards of other people who smoke. This suggests that a complete explanation of nicotine addiction must incorporate social learning theory.

Weaknesses of learning theory explanations of nicotine addiction:

- Incomplete: Learning theory is unable to explain why some people get addicted to nicotine but others don’t. For example, one person might smoke cigarettes occasionally and not become addicted, whereas another person might smoke the same amount and become addicted. This suggests other factors – e.g. genetics, personality – are needed to fully explain why people get addicted to nicotine.

Explanations of gambling addiction

Addiction is typically associated with substances (such as nicotine) that have biological effects in the body. However, people can also get addicted to certain behaviours, such as gambling. Because these behaviours don’t directly cause biological effects in the same way as addictive substances, explanations of gambling addiction tend to be more psychological than biological. The syllabus lists two such examples: Learning theory and cognitive explanations.

Addiction is typically associated with substances (such as nicotine) that have biological effects in the body. However, people can also get addicted to certain behaviours, such as gambling. Because these behaviours don’t directly cause biological effects in the same way as addictive substances, explanations of gambling addiction tend to be more psychological than biological. The syllabus lists two such examples: Learning theory and cognitive explanations.

Learning theory explanations

Learning theory explains gambling addiction as learned behaviour. This primarily occurs through operant conditioning.

The positive reinforcement of gambling is obvious: Winning money. Other factors, such as the lights and sounds of the machines, the social aspect of a casino/betting shop, and the excitement and anticipation of a gamble provide further positive reinforcement. This makes the person more likely to repeat the behaviour.

But gamblers typically lose more money than they win. These losses should serve as negative reinforcement that makes the person less likely to repeat the behaviour. So why do people get addicted to gambling?

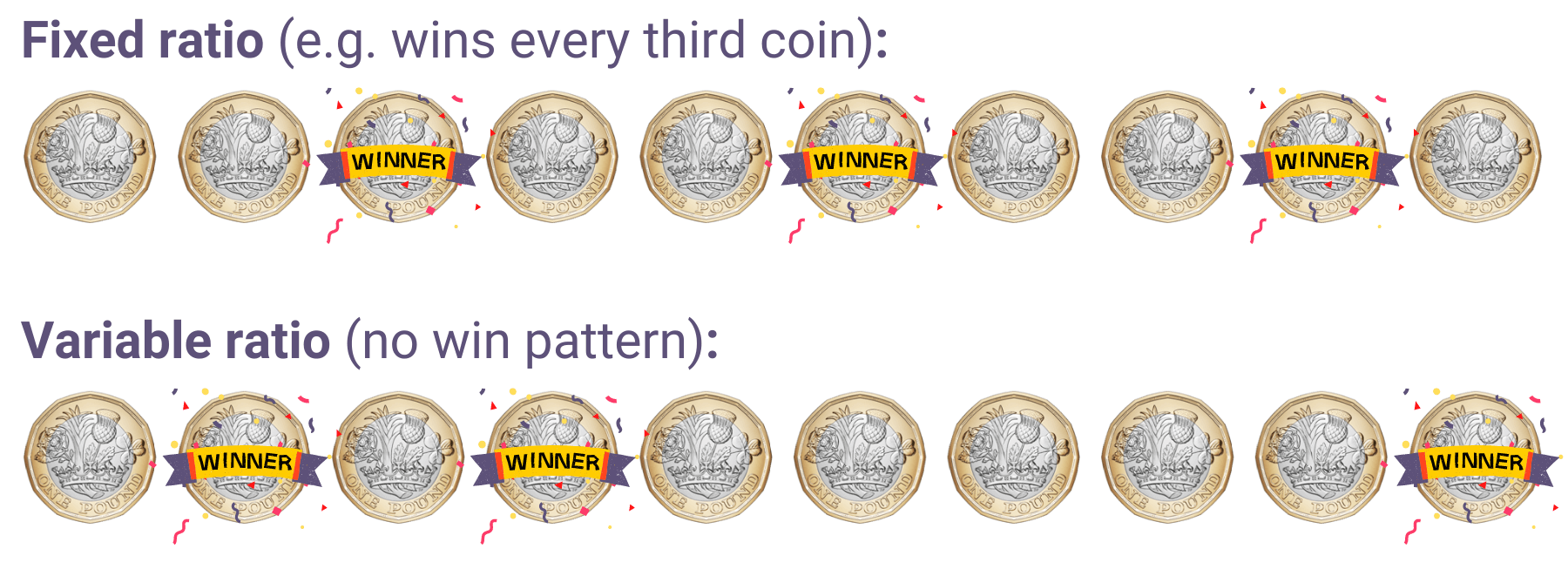

The answer is to do with the schedule of reinforcement. Skinner’s research on rats and pigeons found that schedule was important for creating lasting behavioural change via operant conditioning:

- Continuous reinforcement: When a behaviour is rewarded every time it is performed.

- Partial reinforcement: When behaviour is rewarded some, but not all, times it is performed.

Skinner found that animals rewarded with continuous reinforcement schedules quickly stopped the target behaviour as soon as the rewards stopped. In other words, they soon unlearned the behaviour they had previously been conditioned to learn. However, when the reward schedule was partial and unpredictable, the animals continued the target behaviour for much longer after the rewards stopped.

The same principle applies to gambling addiction. The unpredictability of wins means gambling behaviour is maintained even after successive losses. The gambler thinks “maybe next time I will get a big win”.

Gambling businesses (e.g. casinos, slot machine manufacturers) can use different formulas for partial reinforcement schedules. A slot machine with a fixed ratio, for example, pays out every x spins (or every x minutes). But this is often too predictable, so slot machines typically pay out according to variable ratios:

Variable ratios are typically the most addictive (and most profitable). Again, when the rewards are unpredictable, the gambler thinks “maybe next time”. These thoughts and the gambling behaviour are reinforced with occasional wins, leading to addiction.

AO3 evaluation points: Learning theory explanations of gambling addiction

Strengths of learning theory explanations of gambling addiction:

- Evidence supporting learning theory explanations: Several studies support learning theory explanations of gambling addiction. For example, Parke and Griffiths (2004) describe several ways gambling behaviour is reinforced, such as winning money, the thrill of gambling, and praise from peers. They also argue that some losses – near misses – positively reinforce gambling behaviour, as these raise hopes of future success.

Weaknesses of learning theory explanations of gambling addiction:

- Other factors: Although there is strong evidence supporting the role of operant conditioning in gambling addiction, it does not provide a complete explanation. For example, operant conditioning can’t explain why some people get addicted and others don’t: One person may become addicted to gambling after a few wins whereas another person may never gamble again after the exact same experience. This suggests other factors – e.g. genetics, personality – are needed to fully explain why people get addicted to gambling.

- Doesn’t explain why people start gambling: Operant conditioning only explains why people continue to gamble, not why they start gambling in the first place. As such, other learning theory explanations, such as social learning theory, may be needed to provide a complete account of gambling addiction.

Cognitive explanations

Cognitive explanations of gambling focus on the thought processes of addicts. Gambling addicts are prone to several cognitive biases, such as:

- Overestimating skill: Gambling addicts often believe they have control over things that are just luck. For example, a gambler may believe they can tell where the ball is going to land on a roulette wheel.

- Faulty perceptions: For example, many gamblers believe that past outcomes influence future outcomes even though they are statistically independent, e.g. after a streak of losses, a gambler may think “well, I’m owed a win next time”. This is known as the gambler’s fallacy.

- Rituals: Gambling addicts often have superstitious beliefs and rituals. For example, a gambler may believe that wearing their lucky shirt makes them more likely to win.

- Selective recall: Gambling addicts focus on wins and ignore or forget about losses.

According to cognitive explanations, such irrational thought processes cause and sustain gambling addiction.

AO3 evaluation points: Cognitive explanations of gambling addiction

Strengths of cognitive explanations of gambling addiction:

- Evidence supporting cognitive explanations: A key study supporting cognitive explanations of gambling addiction is Griffiths (1994). In this study, 30 regular gamblers and 30 controls were each given £3 to gamble on slot machines. Griffiths recorded what the participants said as they gambled and interviewed them after. He found that the regular gamblers were more than 5 times as likely to say irrational things (e.g. “the machine doesn’t like me”) as the controls, and that the regular gamblers were significantly more likely to believe winning was about skill rather than luck. This supports the hypothesis that gambling addicts are prone to cognitive bias.

- Practical applications: Understanding the thought processes and cognitive biases of gambling addicts could be used to treat gambling addiction. For example, some addicts may not be aware their thoughts are irrational (e.g. overestimating the role of skill and paying selective attention to wins while ignoring losses) and so cognitive behavioural therapy could help gambling addicts identify these thoughts, challenge them as irrational, and break their gambling addiction.

Weaknesses of cognitive explanations of gambling addiction:

- Methodological concerns: Much of the evidence for cognitive explanations of gambling addiction come from self-report methods, which may not be valid. For example, Dickerson and O’Connor (2006) argue that much of what people say when gambling does not reflect what they actually believe in day-to-day life.

- Correlation vs. causation: As always, you can raise questions about the direction of causation. Even if cognitive bias and gambling addiction are correlated, it doesn’t automatically prove that cognitive bias causes gambling addiction. It could be the case that, over time, gambling addiction causes one’s thinking to become more irrational and biased.

Reducing addiction

There are many different treatments to help reduce addiction, including drug therapy, behavioural approaches, cognitive behavioural therapy, and application of theories such as planned behaviour and Prochaska’s six-stage model. The most effective approach to reducing addiction will depend on what the patient is addicted to and what stage of recovery they’re at.

Drug therapy

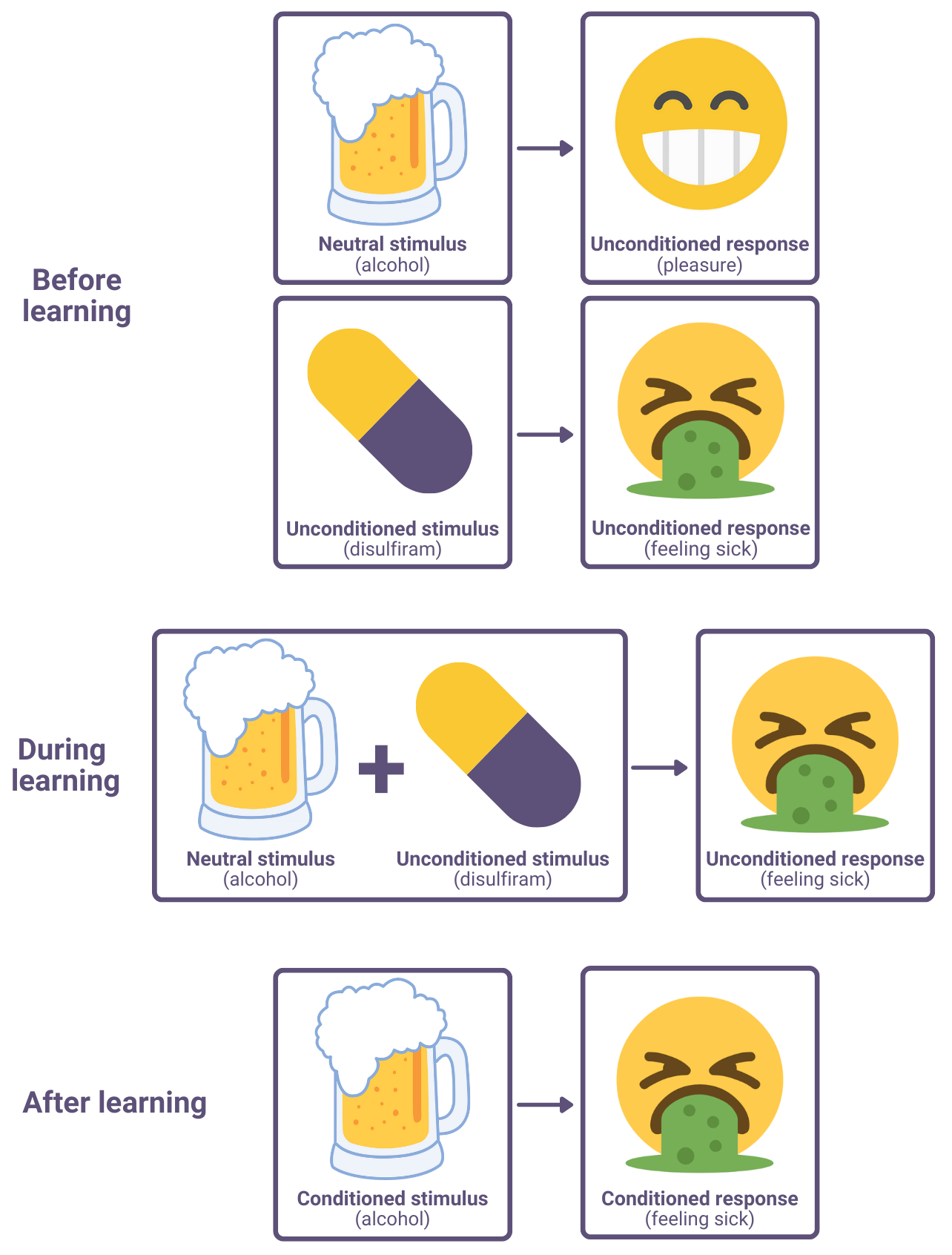

Drug therapy is a biological approach to treating addiction. Drugs used to reduce addiction take several forms:

- Agonists: Create a similar effect to the addictive drug (by activating the same neuron receptors).

- E.g. Methadone causes similar effects to heroin but is longer-lasting and has fewer side effects. Taking methadone reduces the withdrawal symptoms associated with heroin, enabling addicts to taper off the drug more easily.

- Antagonists: Reduces the effects of the addictive drug (by binding to and blocking the neuron receptors the addictive drug acts on).

- E.g. Naltrexone reduces the pleasant feelings caused by heroin and alcohol. This breaks the positive reinforcement of taking these substances, reducing desire to take them.

- Aversive: Causes an unpleasant feeling when the drug is taken. This creates a negative association with the drug via classical conditioning, making the addict no longer want to take it.

- E.g. Disulfiram causes the effects of a hangover (e.g. headache, feeling sick) immediately when combined with small amounts of alcohol.

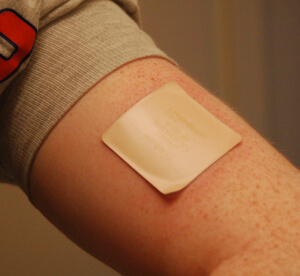

Commonly-used drug therapies for nicotine addiction include nicotine patches, nicotine gum, and nicotine inhalers. These work as agonists by binding to the same receptors (nAChRs) and causing similar effects (e.g. dopamine release). This reduces the withdrawal symptoms when an addict stops smoking.

Commonly-used drug therapies for nicotine addiction include nicotine patches, nicotine gum, and nicotine inhalers. These work as agonists by binding to the same receptors (nAChRs) and causing similar effects (e.g. dopamine release). This reduces the withdrawal symptoms when an addict stops smoking.

Although gambling addiction is not an addiction to a biological substance, drug therapy can still be effective. Gambling activates similar dopamine-related reward pathways to heroin and other drugs, so antagonists such as naltrexone may reduce the desire to gamble. However, it is not officially approved for this use.

AO3 evaluation points: Drug therapy for addiction

Strengths of drug therapy:

- Evidence supporting the efficacy of drug therapy: This obviously varies depending on the drug and which addiction it is used to treat, but several drug therapies are supported by evidence. For example, a systematic review of 11 studies by the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group (2009) found methadone successfully reduces heroin use. For smoking, a meta-analysis by Hughes et al (2003) found over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy (e.g. gum, patches) was effective at helping people quit smoking.

- Can be combined with other therapies: Drug therapy can be combined with other approaches (such as behavioural interventions and cognitive behavioural therapy) to provide a holistic and more effective approach to reducing addiction.

Weaknesses of drug therapy:

- Side effects: Many drugs used to treat addiction have serious side effects that have to be weighed against the benefits. For example, methadone (the agonist used to treat heroin and opiate addiction) is itself highly addictive, although typically less so than the drugs it replaces. Drug therapies may also cause dangerous or unpleasant side effects (e.g. headaches, nausea), which increase the likelihood of the addict discontinuing the therapy.

Behavioural interventions

Behavioural interventions use behaviourist principles to treat addiction. Aversion therapy and covert sensitisation use classical conditioning to create negative associations with the addictive substance or behaviour.

Aversion therapy

Aversion therapy uses classical conditioning to replace the positive associations of an addictive substance with negative associations.

The emetic drug disulfiram (described above) works on this principle: When combined with alcohol, it makes the patient feel very unwell. So, where alcohol would normally cause pleasant sensations, it now creates unpleasant ones. Over time and continued use, the patient learns to associate alcohol with unpleasant sensations even when they no longer take disulfiram.

In addition to emetics (drugs that induce sickness), there are numerous other ways to create negative associations with an addictive substance. For example, researchers have used electric shocks in attempt to treat gambling addiction. And a commonly-used aversion therapy technique for nicotine addiction was to get subjects to rapidly smoke cigarettes one after another, which causes feelings of sickness. The idea with all these methods is to create negative associations with the addictive substance, which should reduce addiction.

AO3 evaluation points: Aversion therapy for addiction

Strengths of aversion therapy:

- Evidence supporting aversion therapy: Although there are few experimental trials, the available evidence suggests emetic drugs are an effective way of reducing alcohol addiction. For example, based on data from private hospitals, Elkins (1991) reports that approximately 60% of alcoholics treated with emetic drugs remain alcohol-free one year later.

Weaknesses of aversion therapy:

- Conflicting evidence: Although there is evidential support for some forms of aversion therapy (e.g. emetic drugs for alcohol addiction), other forms of aversion therapy appear to be less effective. For example, Cannon and Baker (1981) assigned 20 alcoholic subjects to one of three groups: Emetic drugs, electric shock therapy, or no aversion therapy. The researchers found that only the emetic drugs successfully reduced alcohol addiction. Further, in the case of smoking, a review of 25 trials by Hajek and Stead (2001) found insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of aversion therapy for treating nicotine addiction.

- Ethical concerns: Aversion therapy works by inflicting pain and suffering on addicts, which may be considered unethical. In part because of this, aversion therapy has been largely phased out in favour of covert sensitisation.

Covert sensitisation

Covert sensitisation also operates on the behaviourist principle of classical conditioning but uses imagination rather than real-life unpleasant stimuli.

For example, to treat nicotine addiction, a therapist may get the patient to imagine feeling sick while smoking cigarettes. In theory, the stronger and more realistic the mental image is, the more successful the therapy is. So, the therapist may use graphic and disgusting imagery to treat the addiction (e.g. getting the patient to imagine smoking cigarettes covered in faeces). At the end of the session the therapist may get the patient to imagine feelings of happiness at not having to smoke cigarettes and so, in addition to negative associations with smoking cigarettes, the patient will also develop positive associations with not smoking cigarettes.

As with aversion therapy, the goal of covert sensitisation is to turn the unconditioned positive stimulus of the addictive substance/behaviour into a conditioned negative stimulus. This reduces the addiction.

AO3 evaluation points: Covert sensitisation for addiction

Strengths of covert sensitisation:

- Evidence supporting covert sensitisation: Studies suggest covert sensitisation may be an effective treatment for some forms of addiction. For example, in a study of alcohol addicts by Ashem and Donner (1968), 40% of patients treated with covert sensitisation were alcohol-free after 6 months compared to 0% of controls. In the case of gambling addiction, McConaghy et al (1983) randomly assigned 20 gambling addicts to receive either covert sensitisation or aversion therapy via electric shock. After one year, 90% of subjects who received covert sensitisation had reduced their gambling, compared to just 30% for aversion therapy.

- Lower risk of side effects: Covert sensitisation has a much lower risk of side effects than drug therapy and even other behavioural treatments such as aversion therapy. For example, treating alcoholics with disulfiram causes pain and nausea and in extreme cases can result in heart attack and death. In contrast, imagining feeling unwell is less likely to cause severe or lasting negative effects.

Weaknesses of covert sensitisation:

- Conflicting evidence: Although there are examples of success with covert sensitisation, many studies question whether it actually works.

- Differences between patients: Covert sensitisation is likely to be more effective for patients with vivid imaginations. If the patient is unable to picture the negative images in their mind, it won’t create a strong enough association to reduce their addiction.

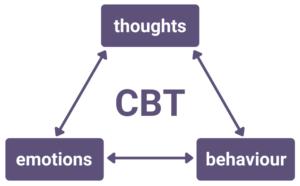

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) involves identifying and challenging the thought processes of addiction. This can be broken down into a cognitive component (functional analysis) and a behavioural component (skills training).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) involves identifying and challenging the thought processes of addiction. This can be broken down into a cognitive component (functional analysis) and a behavioural component (skills training).

With functional analysis, the CBT therapist may get the patient to describe what they think before, during, and after indulging their addiction. The therapist will then help the patient challenge any irrational and maladaptive thought processes during this sequence.

For example, in the case of gambling addiction, the patient may tell themself “I’ll stop when I win back what I’ve lost”. The therapist could then get the patient to reflect on and challenge such thoughts and how they make the situation worse.

The behavioural component of CBT involves helping the patient develop skills to deal with situations that might trigger relapse. For example:

- Drug refusal skills: Social pressures may make it more difficult to give up an addiction. For example, a recovering alcoholic may be offered alcohol at a social event, increasing the likelihood of relapse. The therapist helps the patient identify such social pressures and how to deal with them (e.g. by role-playing refusing alcohol).

- Problem-solving skills: Addicts often relapse when confronted with the problems and stresses of everyday life. The therapist may teach the patient how to deal with these problems (e.g. asking for help, staying focused on the problem). This replaces the unhealthy behaviour (turning to drugs or gambling) with a more healthy alternative.

- Relaxation skills: Many addicts self-medicate to cope with emotions such as stress, anxiety, and anger. For example, a nicotine addict may have reached for cigarettes when they felt stressed. The therapist may teach the patient more healthy ways of dealing with stress (e.g. deep breathing) that replace the addictive substance or behaviour.

AO3 evaluation points: Cognitive behavioural therapy for addiction

Strengths of cognitive behavioural therapy:

- Evidence supporting CBT: Some studies have found CBT to be an effective treatment for addiction. For example, Petry et al (2006) randomly assigned 231 gambling addicts to receive one of three treatment plans: Gamblers Anonymous meetings, Gamblers anonymous meetings + cognitive behavioural workbook exercises, or Gamblers Anonymous meetings + 8 sessions of CBT. The groups that received cognitive behavioural treatments saw greater reductions in gambling activity than those who didn’t, suggesting CBT and related treatments are an effective treatment for gambling addiction.

Weaknesses of cognitive behavioural therapy:

- Questions about long-term efficacy: Although a review by Cowlishaw et al (2012) found CBT to be an effective treatment for gambling addiction in the short term (0-3 months post-treatment), the authors found little evidence to support its efficacy over longer time periods (9-12 months post-treatment). Further, the authors found methodological issues with many of the studies reviewed and argue that this could mean the benefits of CBT are overestimated.

- Lack of standardisation: The many different approaches and methods of CBT make it difficult to determine which aspects of CBT are actually effective (if any).

- Differences between patients: It requires a lot of insight and continuous effort to change one’s thought patterns and so people who are unable to do this are less likely to benefit from CBT. Further, CBT is likely to be more effective for addictions with a strong cognitive basis (e.g. gambling addiction) rather than a biological one (e.g. nicotine addiction).

Theories of behaviour change

Psychologists have developed theories of behaviour change, such as planned behaviour and Prochaska’s six-stage model, that can be applied to addicts to reduce addiction. The idea is that tailoring treatments for each person according to these models will increase the likelihood of behavioural change and reduce their addiction.

Planned behaviour

Building on earlier work (the theory of reasoned action), Ajzen (1991) developed the theory of planned behaviour. According to this theory, changing addictive behaviour is all about intention, which is determined by three factors:

- Personal attitudes: The person’s attitude to their addiction. For example, an addict who recognises that their addiction is having a negative effect on their life is more likely to change their behaviour.

- Subjective norms: The attitudes and norms of the people in their life. For example, if an alcoholic associates with other people who drink a lot and think this is normal, they are less likely to change their behaviour.

- Perceived behavioural control: How much the person believes they are in control of their behaviour. For example, a gambling addict who believes they are too weak-willed to give up their addiction (whether this is true or not) is less likely to stop gambling.

The theory of planned behaviour predicts that the greater the level of intention, the more likely that person is to give up their addiction.

So, in order to improve the likelihood of behavioural change, interventions based on this model should seek to increase the addict’s intention to quit. For example, if a recovering drug addict still associates with other drug addicts, the subjective norms of his peer group will reduce his intention to quit. Tackling this negative peer influence and providing social support from people who do not use drugs will increase his intention to quit, making recovery more likely.

AO3 evaluation points: Planned behaviour theory applied to addiction

Strengths of planned behaviour theory:

- Evidence supporting planned behaviour theory applied to addiction: Hagger et al (2011) found support for all three factors – personal attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control – in predicting an individual’s intention to reduce their drinking. Further, this overall level of intention was also an accurate predictor of units of alcohol consumed, providing support for the validity of the model. In another study on gambling addiction, Oh and Hsu (2001) found correlations between level of intention (as described in the theory of planned behaviour) and actual gambling behaviours, providing further support for the model.

- Practical applications: If intention accurately predicts behavioural change then the theory of planned behaviour will have various practical applications such as more effective treatment strategies and more efficient use of resources. For example, if an alcoholic has no intention to quit (e.g. due to his personal attitudes), then covert sensitisation will likely be a waste of time and money as he will be unlikely to commit to the treatment. Instead, therapies aimed at changing his personal attitudes (and thus increasing his intention to quit) will be more effective.

Weaknesses of planned behaviour theory:

- Conflicting evidence: Although a meta-analysis of 47 studies by Webb and Sheeran (2006) found some correlation between level of intention and behavioural change, the effect was very small. This suggests that the role of intention (the key element of the theory of planned behaviour) may be overestimated in predicting behavioural change.

- Methodological concerns: Testing the theory of planned behaviour requires use of self-report techniques (e.g. questionnaires to gauge personal attitudes), which can be highly unreliable. For example, interpretation of attitudes and social norms is highly subjective and so different participants may report the same information differently. Further, subjects may lie to give socially desirable responses, for example by downplaying the amount of alcohol they drink.

Prochaska’s six-stage model

Behavioural change does not happen instantly. Instead, Prochaska and DiClemente (1983) outline a six-stage model that describes the various steps that occur between addiction and rehabilitation. The idea is that tailoring intervention to each stage of this model increases the likelihood of behavioural change.

| Description | Intervention | |

| Pre-contemplation | The person is not thinking about changing their addictive behaviour at all. They might be in denial (“I’m not an addict”) or demotivated (“What’s the point of trying to quit?”). | Intervention focuses on helping the person recognise that they are an addict (if in denial) and getting them to consider the need to quit. |

| Contemplation | The person is thinking about changing their addictive behaviour in the future (i.e. within the next 6 months). They are weighing up the costs and benefits of quitting. | Intervention focuses on helping the addict reach a decision and realise that the benefits of doing so outweigh the costs. |

| Preparation | The person decides to quit and makes plans to do so in the near future (i.e. within the next month). | Intervention focuses on helping the addict make a plan (e.g. going to see a doctor, joining a support group). |

| Action | The person puts their plan into action and has done something to quit their addiction within the last 6 months. | Intervention focuses on helping the person quit (e.g. social support, coping skills). |

| Maintenance | The person has maintained the behavioural change for over 6 months. They have not relapsed during this time. | Intervention focuses on preventing relapse (i.e. continued support and encouragement). |

| Termination | The person has been abstinent for a long time and is no longer tempted to return to their addiction. Relapse is now highly unlikely. | Intervention is no longer required as the behavioural change has become automatic habit. |

A recovering addict will not necessarily go through these steps in a linear fashion. For example, many people relapse after the maintenance phase and return to e.g. the contemplation or preparation stages. The six-stage model acknowledges relapse as part of the process of behavioural change rather than a failure.

AO3 evaluation points: Prochaska's six-stage model applied to addiction

Strengths of Prochaska’s six-stage model:

- Evidence supporting Prochaska’s six-stage model applied to addiction: A meta-analysis of five studies by Velicer et al (2007) found a consistent success rate of 22-26% for anti-smoking treatment programs tailored to each individual’s stage within the six-stage model. The authors also found that a smoker’s stage within the six-stage model was a more accurate predictor of quitting than demographic factors such as age, race, or gender.

- Practical applications: If Prochaska’s six-stage model is accurate, then it will result in more effective treatment strategies and more efficient use of resources. For example, when someone is in the preparation stage, focusing too much on the costs and benefits of quitting will be a waste of time as the person has already made the decision to quit. Instead, the most effective intervention at this stage will be to help the person make their plan for quitting.

- Positive attitude to relapse: Recovering addicts often relapse several times before quitting their addiction. The six-stage model is realistic in acknowledging this and sees relapse as part of recovery rather than failure.

Weaknesses of Prochaska’s six-stage model:

- Conflicting evidence: Aveyard et al (2009) randomly assigned 2,471 smokers to receive either treatment tailored to their stage on the six-stage model or general treatment that was not tailored to their stage of quitting. The researchers found no significant difference in effectiveness between the two treatments. This suggests that tailoring interventions according to the six-stage model is not effective, contradicting the Velicer et al (2007) study above.

- Arbitrary cut-offs: The six-stage model defines various stages according to time horizons. For example, people in the preparation stage are planning to quit their addiction within the next month, but if someone is planning to quit within the next month + 1 day they are defined as being in the contemplation stage. This cut-off seems arbitrary as there is basically no difference between the two examples in reality. This suggests the stages of the six-stage model are mostly arbitrary and made up rather than accurate descriptions of distinct stages of behavioural change.

<<<Schizophrenia

or:

<<<Eating behaviour

or: