Overview – Social Influence

Social influence looks at how people’s beliefs and behaviours are affected by people around them. A Level psychology looks at the following exaemples of social influence:

- Conformity: Doing what the group does

- Obedience: Doing what an authority figure tells you to do

The syllabus also mentions explanations of resistance to social influence, minority influence, and social change.

Conformity

Conformity, also known as majority influence, is when a person changes their beliefs and behaviour to fit – or conform – to those of a group.

Types of conformity

Kelman (1958) identifies the following 3 types of conformity, going from weakest to strongest:

| Compliance

|

Compliance is the weakest type of conformity. It is where a person publicly changes their behaviour and beliefs to fit that of a group and avoid disapproval. However, privately, the person does not accept the behaviours and beliefs of the group – they just comply with them. An example of compliance would be pretending to like a film you dislike so as not to stand out from a group who all really love that film. |

| Identification

|

Identification is a stronger type of conformity than compliance because it involves the person both publicly and privately changing their behaviour and beliefs to fit that of a group they want to be part of. However, the person only identifies with these beliefs as long as they are associated with the group – upon leaving the group, the original behaviours and beliefs return. An example of identification would be adopting the same music and fashion tastes as your friendship group. When you move away, though, you revert back to your old clothes and music. |

| Internalisation

|

Internalisation is the strongest type of conformity. It is where a person both publicly and privately changes their behaviour and beliefs to those of a group – but permanently. So, unlike identification, individuals who internalise beliefs and behaviours maintain those beliefs and behaviours even after leaving the social group. An example of internalisation would be a person who undergoes a genuine religious conversion. This person will still pray and believe in God even if they move away from the social group of their church. |

Solomon Asch: Conformity experiments

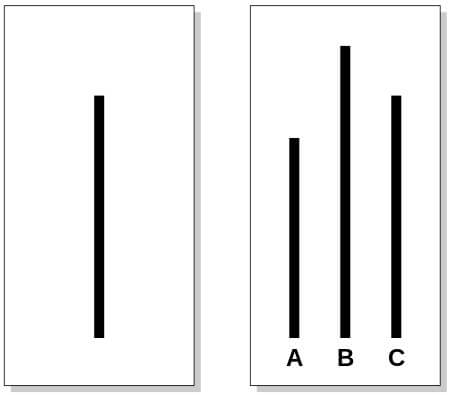

Look at the line in the box on the left. Which of the lines in the box on the right – A, B, or C – is closest in length to it?

This was the question put to participants in Asch (1955). The aim of these experiments was to find out the extent to which people would conform to an obviously wrong majority consensus.

The procedure for the experiments was as follows:

- 123 male participants were told they were taking part in a study of visual perception.

- Participants were put in groups with between 7 and 9 confederates (i.e. fake subjects pretending to be part of the experiment too).

- Each participant completed 18 trials where they would be shown the sets of lines above (A, B, or C) and then asked which one was closest to the original line.

- In the 12 critical trials, the confederates would all give the same wrong answer – the participant was always asked to give their answer last (or second to last) so as to hear the group’s answers first.

- The control group for this experiment consisted of 36 participants. In the control trials, participants were asked the same question as above – but this time alone.

The results of the experiments were as follows:

- Across all critical trials, participants conformed to the incorrect group consensus 32% of the time.

- 75% of participants conformed to at least one incorrect answer

- 5% of participants conformed to every incorrect answer

- This is compared to an error rate of just 0.04% in the control trials.

After the experiment, Asch conducted interviews with the participants. Conforming subjects gave 3 explanations of their conformity:

- Distortion of perception: A small few subjects actually came to perceive the majority estimates as correct and were completely unaware of their mistake.

- Distortion of judgement: The majority of conforming subjects were aware of their mistake but did not trust their own judgement and instead decided that the majority was correct.

- Distortion of action: These subjects were aware of – and trusted – their judgement that the majority was wrong but nevertheless gave the wrong answer so as not to stand out and be different.

AO3 evaluation points: Asch conformity experiments

Strengths of Asch’s conformity experiments:

- Practical applications: Asch’s experiments demonstrate the extent to which humans follow the herd. This is a valuable psychological insight that may have practical applications. For example, understanding the influence of conformity may encourage scientific researchers to think outside of the current paradigm and come up with revolutionary discoveries.

Weaknesses of Asch’s conformity experiments:

- Questions of ecological/external validity: Guessing the length of lines is a specific and unusual task. As such, it is not clear the extent to which Asch’s findings generalise to conformity in the real world.

- Gender bias (beta bias): All the participants in Asch’s study were male, so it is not clear whether the findings are valid in females as well.

- Ethical concerns: Asch told participants they were taking part in a study of visual perception, and thus did not give informed consent to the actual study (which was on conformity).

Variables affecting conformity

In addition to the original experiment above, Asch conducted similar experiments but with different situational variables to see how these affected conformity:

Unanimity

Participants’ conformity declined from 32% to 5.5% when one ‘partner’ confederate was instructed to give the correct answer and go against the incorrect answer of the majority.

Asch’s findings are consistent with other research which finds conformity rates decline when the majority answer is not unanimous. In other words, if the majority all agree, the participant is more likely to conform to the group than if there is some disagreement.

Group size

Increasing the size of the group tended to increase conformity – up to a point. In trials with just one confederate and one participant, conformity rates were low. Increasing the number of confederates to 2 also increased conformity to 12.8% and increasing the number of confederates to 3 increased conformity even further to 32% (the same as the original study). However, adding extra confederates (4, 8, or 16) beyond this did not increase conformity.

Asch’s findings on conformity and majority size have been replicated in other studies, but other studies suggest conformity continues to increase with majority size beyond this.

Difficulty

Increasing the difficulty of the task was also found to increase conformity. Asch adjusted the lengths of the lines in the study above to make it either more easy or more difficult to see which line was closest in length to the original line. If the difference between the incorrect answer and the correct answer was very small (and thus harder to notice), participants were more likely to conform to the incorrect answers of the majority.

Other variables affecting conformity

In addition to Asch’s experiments, psychological research suggests other variables that affect conformity include:

- Mood: Various studies have found correlations between mood and conformity. For example, Tong et al (2008) found that subjects are more likely to conform when they are in a good mood. Further, Dolinski (2001) found that subjecting participants to an “emotional seesaw” (e.g. causing fear then removing fear) makes them more likely to conform.

- Gender: Some research (e.g. Jenness (1932) and Maslach et al (1987)) suggests women are more likely to conform than men.

- Culture: A meta-analysis by Smith and Bond (1996) found that conformity is higher among participants in “collectivist” cultures than “individualist” cultures.

Explanations of conformity

Deutsch and Gerard (1955) explain why people conform by identifying 2 motivating forces: Informational social influence and normative social influence.

Informational social influence (ISI)

People like to feel that their opinions and beliefs are correct – this is informational social influence. This desire to be correct motivates individuals to act on information provided by members of the group because they believe that information to be true or the correct way to do things.

An example of informational social influence is conforming to others’ behaviour at a formal restaurant. You don’t know which cutlery is the correct set to use, so you just copy someone else who seems to know what they’re doing.

Normative social influence (NSI)

People want to be accepted by others and not be rejected – this is normative social influence. This desire to fit in motivates individuals to conform to the beliefs and opinions of a group so as not to stand out. The motivation of normative social influence is not a desire to be correct (like ISI), but is instead a desire to be liked and accepted.

An example of being motivated by normative social influence would be being peer pressured into agreeing with the group’s opinions on politics.

Conformity to social roles

Different social situations have different expectations for behaviour – different social norms. These norms give rise to social roles that people play according to the social situation. We play these different roles – i.e. we conform to social roles – so as to behave correctly and appropriately in society.

For example, in the role of employee, you are expected to show up on time and do your work. In the role of customer in a shop, you are expected to pay for the items you buy.

Philip Zimbardo: Stanford prison study

The aim of the Stanford prison study (Zimbardo et al (1973)) was to find out how much people conform to the social roles of prisoner and guard in a prison situation.

The aim of the Stanford prison study (Zimbardo et al (1973)) was to find out how much people conform to the social roles of prisoner and guard in a prison situation.

The procedure to test this was as follows:

- Zimbardo and his team converted the basement of the psychology department at Stanford University into a fake prison.

- 21 male students were selected from a total of 75 participants for their mental stability and lack of antisocial tendencies.

- These 21 participants were randomly divided into two groups: 10 ‘guards’ and 11 ‘prisoners’

- Prisoners were arrested by real police and then subjected to real police booking procedures (e.g. fingerprinting and mug shots). They were put in cells in groups of 3 and were confined throughout the experiment.

- Guards worked in 8 hour shifts and were instructed to refer to the prisoners by their assigned numbers rather than their names. A realistic prison routine was established with meal times, etc.

- The prisoners wore jackets with their number on, and a chain around one ankle. Guards wore khaki uniforms, mirrored sunglasses to prevent eye contact, and carried handcuffs and wooden batons.

- The study was scheduled to run for 2 weeks.

The results of this observational study were extreme:

- The guards became increasingly sadistic. For example, they forced the prisoners to continually repeat their assigned numbers and made them go to the toilet in buckets in their cells. As punishment, the guards refused to allow prisoners to empty these buckets, took away their mattresses and made them sleep on the concrete floor, and took away their clothes.

- The prisoners became increasingly submissive. Many stopped questioning the guards behaviour and sided with the guards against rebellious prisoners

- After 35 hours, one prisoner began to “act crazy, to scream, to curse, to go into a rage that seemed out of control” and had to be released. Three other prisoners had to be released for similar reasons throughout the duration of the experiment.

- The guards’ sadism became so harmful that Zimbardo stopped the experiment after just 6 days instead of the scheduled 2 weeks.

The results of the prison experiment suggest that people conform to social roles to a significant extent.

In interviews with participants afterwards, both the prisoners and the guards expressed shock at how out-of-character their behaviour had become. Remember, the participants were selected for their mental stability, yet they behaved in ways that they would ordinarily consider to be wrong (particularly the guards). This supports a situational hypothesis of behaviour over a dispositional one: these people did not necessarily have a sadistic disposition, but were instead conforming to the social roles of the situation.

However, it should be noted that not all participants conformed to their roles to the same extent. Some guards did not sadistically exert control and some prisoners did not break down and become totally submissive. This suggests that while situational factors are important, individual dispositions play an important role in behaviour too. Further, some studies designed to replicate Zimbardo’s have challenged his emphasis on social roles.

AO3 evaluation points: Stanford prison study

Strengths of Stanford prison study:

- Practical applications: Zimbardo’s study demonstrates the influence of conformity to social roles, which is an important psychological insight that has resulted in useful applications in society. For example, Zimbardo’s research prompted reform in the way juvenile prisoners were treated (at least initially).

Weaknesses of Stanford prison study:

- Questions of ecological/external validity: Both the guards and prisoners knew they were taking part in a study, and so this might have affected how they behaved. For example, they might have felt they were expected to act a certain way. This is somewhat confirmed by post-study interviews: Many of the participants said they were just acting. As such, the findings of this study may not apply to real life situations.

- Ethical concerns: It’s clear the study subjected many of the participants to high levels of stress, as evidenced by the prisoner who “went crazy” and had to be released, as well as the other participants who had to be released. Further, participants did not explicitly consent to all aspects of the experiment, such as being ‘arrested’ at home.

Obedience

Obedience is when a person complies with – obeys – the orders of an authority figure.

Stanley Milgram: Obedience experiments

The aim of Milgram’s (1963) obedience study was to investigate the extent to which people obey the orders of an authority figure.

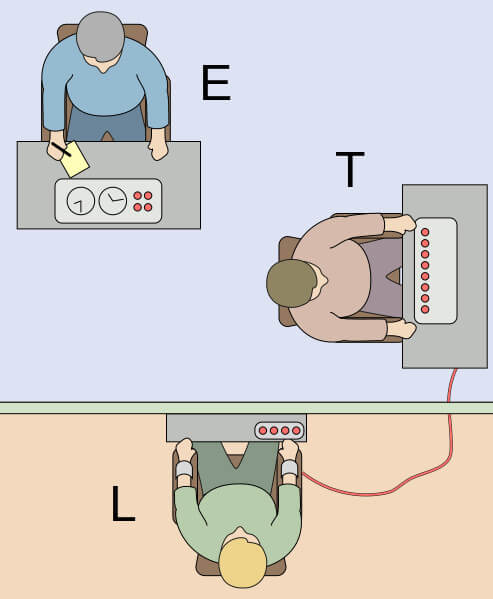

The procedure to test for this – variations of which are now termed the Milgram paradigm – was as follows:

The procedure to test for this – variations of which are now termed the Milgram paradigm – was as follows:

- 40 American male participants aged 20-50 were told they were taking part in an study of the effects of punishment on memory and learning.

- The confederate ‘experimenter’ (wearing a lab coat to create an impression of authority) told the participant that he had been randomly assigned the role of ‘teacher’ and that another participant (who was another confederate) had been randomly assigned the role of ‘learner’.

- The experimenter told the participant the test would involve giving increasingly powerful electric shocks to the learner from a machine in the room next door (marked with different voltage levels).

- The participant watched the learner be strapped into into a chair and have electrodes attached to his body. The participant was also given a 45 volt shock himself so that he believed everything was real.

- The participant teacher (in the room next door) was instructed to teach the learner a list of word pairs. For each wrong answer from the learner, the teacher had to give him an electric shock. These electric shocks increased in power with each wrong answer – starting at 15 volts and increasing by 15 volts each time all the way up to 450 volts.

- Once electric shocks reached 150 volts, the learner began to protest. These protests (pre-recorded and played via a tape recorder) increased in intensity with the increasing voltage. At 315 volts, the learner screamed in pain. After 330 volts, the learner went silent.

- If the participant asked to stop the experiment, the experimenter would reply with one of four successive verbal prods:

- “Please continue” or “please go on”

- “The experiment requires that you continue”

- “It is absolutely essential that you continue”

- “You have no other choice, you must go on”

The results of the experiment were as follows:

- 26 out of 40 participants (65%) administered shocks all the way up to the maximum of 450 volts.

- 40 out of 40 participants (100%) administered shocks up to 300 volts.

- Most participants displayed physical symptoms of discomfort at what they were doing such as sweating, twitching, and nervously laughing. 3 participants suffered seizures from the stress of what they were doing.

Milgram’s study was in part motivated by a desire to understand why Nazi soldiers in World War 2 acted how they did. For example, shortly before Milgram’s study, Adolf Eichmann – a senior Nazi officer responsible for deporting Jews to ghettos and concentration camps – defended his actions at trial by repeatedly saying “I was only following orders”.

Milgram wanted to know if the German people had a uniquely obedient disposition that explained their behaviour. The study suggests not: American people will also obey the demands of an authority figure even if it means going against their moral compass.

AO3 evaluation points: Milgram experiments

Strengths of Milgram’s experiments:

- Reliable: Milgram’s results have been replicated several times over the decades, which suggests the results are reliable.

- Practical applications: Milgram’s experiments demonstrate the extent to which humans obey authority – even if doing so may be dangerous. This is a valuable psychological insight that could have beneficial applications in society. For example, there are several examples of (typically junior) doctors and nurses knowingly following orders that have injured or killed patients. Training junior doctors and nurses of the dangers of obedience (as demonstrated by Milgram’s experiments) could avoid this.

Weaknesses of Milgram’s experiments:

- Unethical: Milgram’s study was initially considered so unethical that Milgram’s membership of the American Psychological Association was suspended. Among the criticisms was the extreme stress placed upon the participants, as evidenced by the 3 who suffered seizures. However, the participants were debriefed after the study and it can be argued that the findings of the experiments are so valuable that the benefits of conducting them outweigh the distress caused to participants.

- Methodological concerns: There have also been several methodological criticisms levelled at Milgram’s study. For example, some psychologists have argued that many participants in Milgram’s study didn’t actually believe the shocks were real. If so, then Milgram’s findings would likely not be valid when applied to real life. However, in post-study interviews, 75% of participants said they believed the shocks were real. And further, the physiological symptoms of stress observed in many of the participants suggest they really did believe they were inflicting harm.

Variables affecting obedience

Milgram conducted variations of the original experiment above to test how different situational variables affect obedience:

Proximity

In subsequent studies, Milgram found that obedience declined if the participant was physically closer to the learner. For example, when the participant and the learner were in the same room, obedience fell to 40% from 65%. In one experiment, the participant teacher had to actually hold the learner’s arm onto a shock plate, which resulted in just 30% of participants completing the experiment (again vs. 65% in the original experiment).

The proximity of the authority figure also affects obedience. In experiments where the experimenter gave instructions to the participant via telephone, obedience fell to 21% compared to the original 65%.

Location

Milgram also carried out the study in different settings and found that obedience increases in institutional and official-seeming environments. For example, Milgram’s original experiment (65% obedience) was conducted at the prestigious Yale University. But when Milgram replicated the experiment in an office in a bad part of town, obedience dropped to 47.5%.

Uniforms

In Milgram’s original experiment, the experimenter wore a lab coat and instructed the teacher to increase the voltage. However, in another variation of the experiment, the experimenter was replaced mid-way through by someone wearing ordinary clothes, who told the participant to increase the voltage with each wrong answer. In this variation, obedience was 20% rather than 65%.

In Milgram’s original experiment, the experimenter wore a lab coat and instructed the teacher to increase the voltage. However, in another variation of the experiment, the experimenter was replaced mid-way through by someone wearing ordinary clothes, who told the participant to increase the voltage with each wrong answer. In this variation, obedience was 20% rather than 65%.

The influence of uniform is further supported by Bickman (1974). Bickman found that 38% of participants obeyed the orders of someone wearing a security guard’s uniform compared to 19% when wearing ordinary clothes and 14% when wearing a milkman’s uniform.

Explanations of obedience

Agentic state

Milgram’s distinction between an agentic state and autonomous state explains (at least partly) why people obey authority:

- Autonomous state: When an individual is freely and consciously in control of their actions and thus takes responsibility for them.

- Agentic state: When an individual becomes de-individuated and considers themselves an agent (tool) of an authority figure and thus not personally responsible for their actions.

According to Milgram’s theory, we are taught from a young age that obedience is necessary for an orderly society. But this requires individuals to give up some amount of free will. In situations where an individual obeys an authority figure, they (mentally) hand over responsibility for their actions to the person giving the orders. In the agentic state, a person will obey instructions that go against their moral compass because they do not consider themselves personally responsible for them.

Legitimacy of authority

Another reason for obedience is that individuals may accept an authority figure has a legitimate right to be giving orders. This ties in with the agentic state: we are taught that obedience to authority figures (e.g. parents, teachers, police) is necessary for an orderly society and thus are more likely to do as they say.

Some of the variables in Milgram’s experiments clearly added to the perceived legitimacy of the experimenter’s authority. Participants were more likely to obey the experimenter if he was wearing a lab coat, and the prestigious location of Yale University likely increased the perceived legitimacy of the experimenter in the participant’s eyes. If a person accepts an authority figure as legitimate, that person will feel they have a duty to do as the authority figure says.

The dispositional explanation of obedience: The authoritarian personality

A further explanation of obedience is that some people have an inherent disposition towards obedience. This would be an internal explanation of obedience because it explains obedience as part of someone’s personality rather than an external one that explains obedience as a result of the environment they are in.

Milgram wanted to know if the German people were uniquely disposed towards obedience and concluded not. However, within populations (German, American, or other), there may be individuals whose personality is more disposed to obedience and authoritarianism. Psychologist Erich Fromm proposed the authoritarian personality: people whose disposition makes them submissive to authority and dominating of people with lower status within the hierarchy and members of an out-group.

Adorno et al (1950) created the F-scale personality test to measure the authoritarian personality in people. In later research, Milgram found that people who were highly obedient in his experiments scored higher on the F-scale than those who disobeyed. This suggests that the authoritarian personality type can (at least partly) explain obedience.

Resistance to social influence

Social influence has both positive and negative effects. It would be a chaotic society if nobody ever conformed to social roles (e.g. children just ignored parents, students ignored teachers, etc.) and things like teamwork would be practically impossible. But sometimes social influence can have negative effects, like being peer-pressured into dangerous behaviour or obeying an authority figure who is asking you to do something immoral (e.g. Milgram’s experiments).

So, sometimes individuals may choose to assert their own free choice and resist social influence. To resist conformity is non-conformism, and to resist obedience is disobedience.

So, sometimes individuals may choose to assert their own free choice and resist social influence. To resist conformity is non-conformism, and to resist obedience is disobedience.

Explanations of resistance to social influence

Social support

Having another person on your side (social support) greatly reduces the effects social influence – increasing both non-conformism and disobedience:

Conformity: As mentioned above, Solomon Asch observed that participant conformity declined from 32% to 5.5% when one of the confederates went against the group and said the correct answer. Having someone else break the unanimity of the group provided social support for the participant to give the answer he really thought.

Obedience: In another variation of Milgram’s experiments, participants took part in the experiment with two other (confederate) teachers. When the other teachers refused to administer any more electric shocks and left the study, participant obedience dropped from 65% to 10%.

Locus of control

Rotter (1966) developed a scale to measure a person’s locus of control, which is the extent to which they believe they are in control of their life:

- Internal locus of control: The person believes their own choices shape their life

- E.g. if you do badly in an exam, you blame yourself

- External locus of control: The person believes their life is controlled by things outside their control – such as luck, fate, and circumstance

- E.g. if you do badly in an exam, you blame the exam paper or the teacher

Whether a person has an internal or external locus of control may affect their level of conformity and obedience:

Conformity: A meta-analysis by Avtgis (1998) found that people with an internal locus of control are less likely to conform to group influence than people with an external locus of control.

Obedience: Research linking obedience and locus of control is more mixed, but leans in the direction of also suggesting that those with an internal locus of control are less likely to obey an authority figure than those with an external locus of control. This may be because people with an internal locus of control feel they have control over their actions and thus are able to resist the influence of an authority figure.

Other factors affecting resistance to social influence

Resistance to conformity:

- Status: People with low status within a group may be motivated to conform to the group in order to gain status.

- Ironic deviance: If a person feels that the group consensus has been artificially manufactured, they are less likely to conform to it. For example, Conway and Shaller (2005) describe how an office worker who sees his colleagues all using a particular software program may infer that it is good and conform by using it himself, but if he knows they are all using that product simply because the boss told them to use it he may be less likely to conform because he will not perceive the consensus as genuine.

Resistance to obedience:

- Systematic processing: If people are given the opportunity to think through their actions systematically, they may be more likely to disobey unreasonable orders (e.g. Martin et al (2007)).

- Moral beliefs: People who base decisions on moral principles may also be less likely to obey immoral orders. For example, Milgram described how one of the participants – a vicar – disobeyed the experimenter because he was “obeying a higher authority” (God). This is further supported by research from psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg, who tested participants from Milgram’s studies and found those who based decisions on moral principles were less likely to obey.

- Reactance: If people feel an authority figure is restricting their free will, they may deliberately go against the authority figure to reassert their free will.

Social change

The social norms of society (i.e. the expected rules for behaviour) are largely determined by majority influence. Social change is the process by which these norms change over time.

Minority influence

Minority influence is an important factor for social change. Although majority influence (conformity) determines current social norms, minority influence can convert individuals to reject these social norms and adopt the beliefs and behaviours of a minority. Eventually, if enough people are converted to the minority’s beliefs, they become the new majority and establish new social norms.

An example of minority influence would be the spread of Christianity: the minority influence of this initially small movement converted many European countries to become majority Christian. Another example of minority influence would be the suffragettes converting the majority to accept women’s rights to vote.

Social cryptoamnesia is the process whereby the minority influences a few members of the majority at first, but as these numbers grow it causes a snowball effect where more and more members of the majority get converted at a growing pace.

Variables affecting minority influence

The following 3 variables increase the effectiveness of minority influence: Consistency, commitment, and flexibility.

Consistency and commitment

Moscovici and Naffrechoux (1969) conducted experiments on minority influence. Participants were divided into groups of 6 (4 real participants and 2 confederates) and told they were taking part in a study of visual perception. The participants were shown 36 shades of blue and asked to say out loud what the colour was.

- In the control group (no confederates), participants said the colours were green 0.25% of the time.

- In the inconsistent minority group (where confederates said 24/36 colours were green), participants said the colours were green 1.25% of the time.

- In the consistent minority group (where confederates said 36/36 colours were green), participants said the colours were green 8.4% of the time.

This suggests minority influence is more effective when the minority are consistent in their beliefs and behaviours.

Moscovici also argues that minority influence is most effective when the minority remain committed to their beliefs over time (especially in the face of adversity).

Flexibility

Although consistency is important, minority influence is less effective if the minority is completely inflexible and unwilling to compromise with the majority.

For example, Nemeth (1986) divided participants into groups of 4 (with 1 confederate) to negotiate how much insurance money to pay someone. She found that confederates who demonstrated flexibility were more effective at persuading the majority to accept a low amount than confederates who inflexibly stuck to a very low amount.