Overview – Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a psychological disorder characterised by loss of contact with reality. This A Level psychology topic looks at the symptoms of schizophrenia and how it is diagnosed, as well as various approaches to explaining and treating schizophrenia:

- The biological approach to schizophrenia (including genetic explanations, neural explanations, and the dopamine hypothesis, as well as drug therapy as treatment for schizophrenia)

- Psychological approaches to schizophrenia (including family dysfunction and cognitive explanations of schizophrenia, as well as treatments including CBT, family therapy, and token economies)

- Interactionist approaches to schizophrenia (including the diathesis-stress model)

Classification of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a psychological condition characterised by a loss of contact with reality. It affects around 0.7% of the population. There is no single defining symptom of schizophrenia but a cluster of (often seemingly unrelated) symptoms. These symptoms may be positive (experiences in addition to ordinary experience, such as hallucinations) or negative (a lack of abilities associated with normal experience, such as reductions in speech).

Positive symptoms of schizophrenia

Positive symptoms are additional experiences beyond those associated with normal psychological functioning. Positive symptoms associated with schizophrenia include hallucinations and delusions.

Positive symptoms are additional experiences beyond those associated with normal psychological functioning. Positive symptoms associated with schizophrenia include hallucinations and delusions.

Hallucinations

Hallucinations are perceptions that are not based in reality, or distorted perceptions of reality.

For example, a schizophrenic person may hallucinate hearing voices that aren’t really there, or seeing someone who isn’t really there.

Delusions

Delusions are beliefs that are not based in reality.

For example, a schizophrenic person may have a delusion that they are the victim of a grand conspiracy, or that they are an important person with a unique mission (e.g. Jesus Christ reborn).

Negative symptoms of schizophrenia

Negative symptoms are a lack of abilities associated with normal psychological functioning. Negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia include speech poverty and avolition.

Speech poverty

Speech poverty is a reduction in the quality and amount of speech.

For example, a schizophrenic person may give one-word answers to questions without elaborating any further detail.

Avolition

Avolition is a lack of desire and motivation for anything.

For example, a schizophrenic person may sit around without engaging in everyday tasks such as work, socialising, or maintaining personal hygiene.

Diagnosis of schizophrenia

There are two main classification systems for diagnosing schizophrenia: The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and the World Health Organisation’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). These manuals enable doctors to label a patient’s symptoms as those of schizophrenia (rather than some other disorder).

The criteria for DSM-5 and ICD-10 differ slightly: DSM-5 requires at least one positive symptom to be present, whereas diagnosis of schizophrenia using ICD-10 can be based on negative symptoms alone.

Reliability of schizophrenia diagnosis

Reliability refers to how consistently schizophrenia is diagnosed. For example, if multiple different doctors diagnose the same person as schizophrenic based on the same symptoms, then their diagnosis is reliable.

Various studies have attempted to quantify the reliability of schizophrenia diagnosis. For example:

- Beck et al (1962) found a concordance rate of 54% among psychiatrists in their diagnosis of schizophrenia.

- Söderberg et al (2005) found a concordance rate of 81% among psychiatrists using the DSM classification to diagnose schizophrenia.

- Jakobsen et al (2005) found a concordance rate of 98% among psychiatrists using the ICD-10 classification to diagnose schizophrenia.

- In Cheniaux et al (2009), two psychiatrists evaluated 100 patients using both the DSM-4 and ICD-10 criteria. Psychiatrist 1 found 26 patients had schizophrenia according to DSM-4 and 44 according to ICD-10. Psychiatrist 2 found 13 patients had schizophrenia according to DSM-5 and 24 according to ICD-10. This suggests both low inter-observer reliability and low reliability between the two classification systems.

AO3 evaluation points: Reliability of schizophrenia diagnosis

- Improvements in inter-observer reliability: Although research is conflicting (see studies above), more recent studies of schizophrenia diagnosis generally find higher concordance rates among psychiatrists compared to older studies. This suggests that diagnosis of schizophrenia has become more reliable over time.

- Low reliability between DSM and ICD: Cheniaux et al (2009) demonstrates different incidence of schizophrenia diagnosis by the same observer depending on which manual they use. In general, the DSM classification is considered more reliable as the descriptions of symptoms are more specific.

- Co-morbidity: People with schizophrenia often suffer from psychological disorders in addition to schizophrenia, which confuses diagnosis. For example, people with schizophrenia often suffer from depression as well. This can reduce the reliability of diagnosis as one evaluator may pick up on the depressive symptoms and diagnose the patient with depression, whereas another evaluator may pick up on the schizophrenic symptoms and diagnose the patient with schizophrenia.

Validity of schizophrenia diagnosis

Validity refers to how accurately schizophrenia is diagnosed. For example, if doctors frequently diagnose patients with autism as suffering from schizophrenia, then their diagnosis is not valid.

Rosenhan (1973) questions the validity of schizophrenia diagnosis. In this study, eight healthy volunteers (i.e. subjects who did not have schizophrenia) presented themselves to various psychiatric hospitals claiming to hear voices. All eight volunteers were successfully admitted to the hospitals and diagnosed with schizophrenia. Depending on the ‘patient’, doctors took between 7-52 days to release them. In a later experiment, doctors were falsely told that healthy patients would attempt to admit themselves, which led doctors to turn genuine schizophrenic patients away because they thought they were actors. The results of these experiments suggest the doctors did not have valid methods for diagnosing schizophrenia.

AO3 evaluation points: Validity of schizophrenia diagnosis

- Improvements in validity: Although Rosenhan (1973) casts doubt on the validity of schizophrenia diagnosis, more recent studies suggest schizophrenia diagnosis has become more accurate. For example, Mason et al (1997) found that improvements to diagnostic manuals (DSM and ICD) over time led to more accurate diagnosis of schizophrenia.

- Symptom overlap: Schizophrenia shares symptoms with other psychological disorders, such as depression and autism. For example, both people with schizophrenia and people with autism often suffer with speech poverty. This overlap of symptoms may reduce the validity of schizophrenia diagnosis because an evaluator may incorrectly attribute these symptoms to a different disorder.

- Gender differences: Several studies suggest differences between men and women in the rates of schizophrenia, average age of onset, and severity of symptoms. For example, a meta-analysis from Aleman et al (2003) found men were 42% more likely to suffer from schizophrenia than women. This is supported by Castle et al (1993), who found that when diagnostic criteria were strictly defined, the rate of schizophrenia in men was more than twice that of women. Is this disparity a result of gender bias in diagnosis, or do these findings reflect a valid difference in the incidence of schizophrenia between men and women? Cotton et al (2009) suggest that the better interpersonal functioning of women may cause doctors to miss schizophrenia diagnosis in women, supporting the existence of gender bias. However, Kulkarni et al (2001) found that administration of estrogen (the female hormone) reduces schizophrenia symptoms, which suggests biological differences may partly explain gender differences in schizophrenia.

- Cultural differences: Several studies (e.g. Cochrane (1977), McGovern and Cope (1987), and Ineichen et al (1984)) have found ethnic minorities living in Britain (particularly those of Afro-Caribbean descent) are diagnosed with schizophrenia at higher rates than white people. However, rates of schizophrenia diagnosis among Afro-Caribbean people living in the Caribbean are roughly the same as white people in Britain. This suggests either:

- Invalid diagnosis: Afro-Caribbean people in Britain are being overdiagnosed with schizophrenia due to cultural bias (or Afro-Caribbean people in the Caribbean are being underdiagnosed).

- Valid diagnosis: The diagnosis reflects a valid difference in schizophrenia rates and so environmental stressors in Britain (e.g. racism, increased risk of flu) are causing increased rates of schizophrenia among people of Afro-Caribbean descent.

Biological approach to schizophrenia

Biological explanations of schizophrenia

Biological explanations of schizophrenia look at biological factors linked to schizophrenia. These include genetics, neural (brain) abnormalities, and abnormalities in dopamine.

Genetics

The genetic explanation of schizophrenia looks at hereditary factors – i.e. genes – that contribute to the development of schizophrenia.

As always, twin studies are a useful way to determine whether or not a condition is inherited through genetics. If it is more common for both identical twins to suffer from schizophrenia than it is for both non-identical twins, this would suggest a genetic component to schizophrenia. The reason for this is that identical twins have 100% identical genetics whereas non-identical twins only share 50% of their genes and so any genetic condition would be equally common to both identical twins.

Several studies have attempted to determine the genetic heritability of schizophrenia. Perhaps the most widely-cited source is Gottesman (1991), who looked at how different familial relationships to someone with schizophrenia are linked with risk of developing schizophrenia:

Gottesman found that the closer the genetic relationship to the person with schizophrenia, the greater the risk of developing schizophrenia. For example, the concordance rate for schizophrenia among identical twins is 48%, whereas for non-identical twins it is 17%. This supports the idea that genetics play a role in developing schizophrenia.

Other familial and twin studies into schizophrenia include:

- Cardno et al (1999) found identical twins had a concordance rate for schizophrenia of 40.8%, whereas non-identical twins had a concordance rate of 5.3%.

- Tienari et al (1985) conducted a longitudinal study comparing adopted children whose biological mothers had schizophrenia with a control group of adoptees whose biological mothers did not have schizophrenia. The researchers found that the children of schizophrenic mothers were more likely to develop schizophrenia compared to controls, supporting the role of genetics in the development of schizophrenia.

- Kety and Ingraham (1992) is another adoption study. Adoption studies like this are useful because they separate (and thus control for) environmental factors: If schizophrenia was passed on from parents to children through environmental factors only, you would expect adoptees whose biological parents had schizophrenia to have the same rates of schizophrenia as the control group. However, the researchers found that adoptees whose biological parents had schizophrenia were 10 times more likely to develop schizophrenia than a control group of adoptees whose biological parents did not have schizophrenia, supporting a genetic basis of the disorder.

AO3 evaluation points: Genetic explanations of schizophrenia

Strengths of genetic explanations of schizophrenia:

- Supporting evidence: The familial and twin studies of schizophrenia above support the genetic explanation of schizophrenia because they show that being closely related (and thus having similar genes) to someone with schizophrenia increases the likelihood of suffering from schizophrenia.

- Multiple genes: It is unlikely that there is a single gene responsible for schizophrenia. Instead, multiple genes likely combine to increase a person’s risk of developing schizophrenia. In a study of more than 36,000 schizophrenic patients, Ripke et al (2014) found 108 different genetic variations that were correlated with schizophrenia, supporting the existence of a genetic component to the disorder. Further, many of these genetic variations were related to dopamine transmission, so genetic explanations can be combined with the dopamine hypothesis to provide a holistic explanation of schizophrenia.

Weaknesses of genetic explanations of schizophrenia:

- Other factors: Although most studies suggest genetics play a part in the development of schizophrenia, it is clear that other factors are important too. If schizophrenia was 100% genetic, you would expect concordance rates between identical twins to be 100%. However, most studies find concordance rates among identical twins to be less than 50%, which suggests there is more to schizophrenia than just genetics. This suggests an interactionist approach is best for explaining schizophrenia.

- Methodological issues surrounding twin studies: Twin studies typically assume that twins have identical upbringings and so any differences in concordance rates between identical and non-identical twins must be explained by genetics. However, environmental factors likely play a role too. For example, looking identical probably makes parents treat identical twins more similarly than they would non-identical twins. As such, greater similarities in environment could contribute to higher concordance rates for schizophrenia among identical twins, with the influence of genetics being exaggerated.

Neural correlates

The neural explanation of schizophrenia looks at correlations among the brain structures of people with schizophrenia.

There are several ways to examine the brain, such as post-mortem and fMRI scanning. By using these methods, researchers can compare the brains of schizophrenic people with non-schizophrenic people to identify differences in brain structures that may cause schizophrenia.

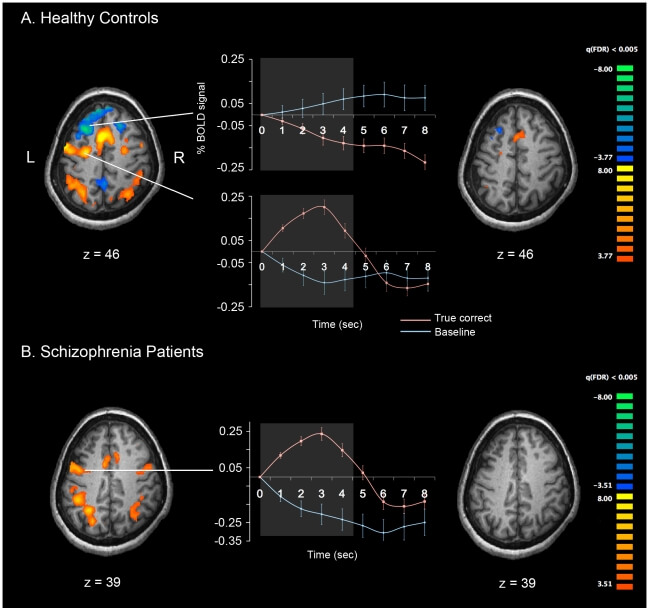

For example, the images above from Kim et al (2010) show fMRI scans of a schizophrenic patient and a non-schizophrenic control during a working memory task.

Other studies looking at the neural basis of schizophrenia include:

- Enlarged ventricles: Several studies have found correlations between enlarged ventricles in the brain and schizophrenia. For example, Johnstone et al (1976) and Suddath et al (1990). Enlarged ventricles are particularly linked with the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, as shown in studies such as Andreasen et al (1982).

- Reduced grey matter and cortical thinning: Boos et al (2012) compared MRI scans of 155 schizophrenic patients, 186 non-schizophrenic family members, and 122 non-schizophrenic controls. The researchers found that the schizophrenic patients had reduced grey matter and cortical thinning compared to their non-schizophrenic family members and the non-schizophrenic controls. This further supports the existence of a neural basis for schizophrenia.

- Facial emotion processing: A common symptom of schizophrenia is difficulty perceiving emotions. A meta-analysis by Li et al (2010) looked at fMRI scans of schizophrenic patients and non-schizophrenic controls during facial expression processing tasks. The researchers found that people with schizophrenia have reduced activity in the bilateral amygdala and right fusiform gyri compared to controls, suggesting a neural basis for this symptom.

AO3 evaluation points: Neural explanations of schizophrenia

Strengths of genetic explanations of schizophrenia:

- Supporting evidence: The studies above support several neural explanations of schizophrenia because they demonstrate correlations between neural structures and schizophrenia.

Weaknesses of neural explanations of schizophrenia:

- Conflicting evidence: Although several studies have found correlations between enlarged ventricles and schizophrenia, there are many exceptions. There are many people with enlarged ventricles who do not have schizophrenia, and there are many people with schizophrenia who do not have enlarged ventricles.

- Correlation vs. causation: Although there are correlations between schizophrenia and certain neural patterns, it can be difficult to determine whether abnormal brain functioning causes schizophrenia symptoms or whether it is an effect of schizophrenia. For example, does reduced activity in the bilateral amygdala of schizophrenic patients cause difficulties in emotional processing, or do schizophrenics’ reduced emotional processing (caused by some other factor) result in reduced blood flow and activity in the bilateral amygdala?

The dopamine hypothesis

The dopamine hypothesis explains schizophrenia (at least partly) as a result of abnormal activity of the neurotransmitter dopamine.

The dopamine hypothesis explains schizophrenia (at least partly) as a result of abnormal activity of the neurotransmitter dopamine.

The dopamine hypothesis became popular in the 1970s when studies (e.g. Seeman et al (1976), Creese et al (1976), and Snyder (1976)) reported that several drugs that reduce schizophrenia symptoms are dopamine receptor antagonists: They reduce dopamine activity. The implication is that schizophrenia is caused by increased dopamine activity and that these drugs work by reducing dopamine activity.

Further evidence supporting the dopamine hypothesis includes:

- Dopamine agonists: Several studies have demonstrated that drugs that increase dopamine activity – dopamine agonists, such as amphetamines – can induce schizophrenic symptoms in non-schizophrenic people. For example, a systematic review by Curran et al (2004) found that amphetamine use makes schizophrenia symptoms worse in schizophrenic patients. Further, McKetin et al (2013) found that non-schizophrenic methamphetamine addicts demonstrated a 5-fold increase in schizophrenia-like symptoms during periods when they were using methamphetamine. This link is further supported by animal studies, such as Randrup and Munkvad (1966), who were able to induce schizophrenic behaviour in rats with amphetamines and then reverse these symptoms with dopamine-reducing drugs (antagonists).

- Post-mortem evidence: Bird et al (1979) used post-mortems to compare dopamine levels in the brains of 50 schizophrenic patients with 50 non-schizophrenic controls. The schizophrenic patients had increased dopamine concentrations in some areas of the brain compared to controls.

- Brain scans: Some studies using brain-scanning techniques have found increased dopamine activity in schizophrenic patients. For example, Lindström et al (1999) compared PET scans of 12 schizophrenic patients with 10 controls and found the schizophrenic patients had increased dopamine activity in the striatum and parts of medial prefrontal cortex. Further, a review of MRI scans by Alves et al (2008) found support for the (revised) dopamine hypothesis.

Over the years, the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia has been refined. It’s not as simple as high dopamine = schizophrenia. Instead, research suggests that schizophrenia is linked with high dopamine activity in some areas of the brain (e.g. the subcortex) but low dopamine activity in other areas (e.g. prefrontal cortex).

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia remains somewhat controversial. The AO3 evaluation points below provide examples of evidence against the dopamine hypothesis.

AO3 evaluation points: The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia

Strengths of the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia:

- Supporting evidence: The studies above support the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia in several different ways. For example, drugs that lower dopamine have been shown to reduce schizophrenia symptoms, and brain scans have shown higher dopamine activity in schizophrenic patients.

Weaknesses of the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia:

- Conflicting evidence: Farde et al (1990) compared brain scans of 18 schizophrenia patients with 20 non-schizophrenic controls. They found no difference in dopamine activity between the two groups. Similarly, in a review of post-mortem studies, Haracz (1982) found little evidence to support the dopamine hypothesis.

- Other neurotransmitters: Evidence suggests that other neurotransmitters besides dopamine are involved in the development of schizophrenia, such as glutamate and serotonin. For example, a meta-analysis of brain scans by Marsman et al (2013) found decreased glutamate activity in schizophrenic patients compared to controls. Further, like with the dopamine hypothesis, there is some evidence that drugs that alter glutamate activity can successfully treat schizophrenia. It’s important to note that the glutamate hypothesis does not contradict the dopamine hypothesis: Both neurotransmitters may be involved in schizophrenia. Serotonin may also be implicated in schizophrenia, as suggested by the efficacy of atypical antipsychotic drugs.

- Allegations of bias: Psychiatrist David Healy (2002) argues that pharmaceutical companies exaggerated the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia to sell more drugs. The overly-simplified hypothesis that schizophrenia is caused by high dopamine makes it easy to market antipsychotic drugs as ‘cures’ for schizophrenia.

Biological treatment of schizophrenia: Drug therapy

Antipsychotic drugs are the primary biological treatment for schizophrenia. These drugs are divided into two categories: Typical antipsychotics and atypical antipsychotics.

| Typical antipsychotics |

Atypical antipsychotics |

|

| Other names | First-generation | Second-generation |

| Used since | 1950’s | 1970’s |

| Aim | Reduce symptoms of schizophrenia | Reduce schizophrenia symptoms more effectively with less side effects |

| Neurotransmitters targeted | Dopamine | Dopamine and others (e.g. serotonin and glutamate) |

| Examples | Chlorpromazine Haloperidol |

Clozapine Risperidone |

Typical antipsychotics

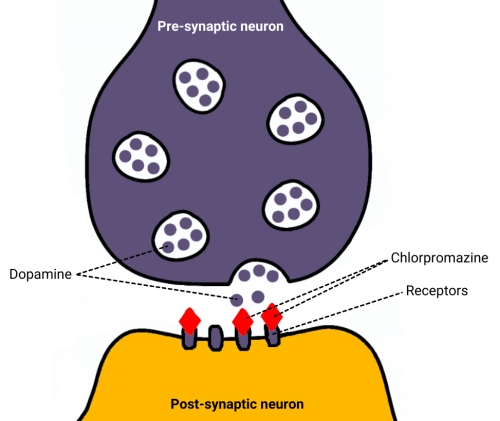

Typical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia work by reducing dopamine activity – they are dopamine antagonists – and are thus strongly associated with the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. They have been used since the 1950’s and are sometimes referred to as first-generation antipsychotics.

Chlorpromazine was the first antipsychotic drug developed. It is a dopamine antagonist, which means it works by blocking dopamine receptors in the brain. Chlorpromazine also has sedative effects.

Typical antipsychotic drugs, such as chlorpromazine and haloperidol, can cause several side effects. Among the most serious of these side effects are extrapyramidal symptoms, which are problems with movement similar to Parkinson’s disease.

Atypical antipsychotics

Atypical antipsychotic drugs have been around since the 1970’s and are sometimes referred to as second-generation antipsychotics. The aim of these drugs is to improve upon the efficacy of typical antipsychotics while reducing side effects.

Atypical antipsychotics target several neurotransmitters, not just dopamine. For example, clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic that acts on the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. Risperidone, another atypical antipsychotic, targets dopamine and serotonin.

Some evidence suggests atypical antipsychotics are superior to typical antipsychotics (see AO3 evaluation points below). However, atypical antipsychotics also carry a risk of side effects including weight gain, increased risk of heart attack, increased risk of diabetes, and extrapyramidal symptoms.

AO3 evaluation points: Drug therapy for schizophrenia

In general, there is no one-size-fits-all drug therapy for schizophrenia. The different mechanisms of action and side effect profiles of the various drugs (both typical and atypical) mean the best treatment option will vary from patient to patient. Further, drug therapy can be combined with psychological treatments such as CBT.

Strengths of drug therapy:

- Evidence supporting drug therapy: Several studies have found both typical and atypical antipsychotics to be more effective than placebo in reducing schizophrenia symptoms.

- Atypical antipsychotics more effective than typical antipsychotics: A systematic review by Bagnall et al (2003) looked at data from over 200 trials of antipsychotic drugs. In general, atypical antipsychotics were more effective than typical antipsychotics. However, data supporting the most recent atypical antipsychotics was of poor quality.

Weaknesses of drug therapy:

- Criticism of the distinction between typical and atypical: While atypical antipsychotics were designed to be more effective with less side effects than typical antipsychotics, some studies question whether this is actually the case. Further, while typical antipsychotic drugs were thought to target the dopamine neurotransmitter only, more recent evidence suggests both generations of antipsychotics target other neurotransmitters such as serotonin. For these reasons, some commentators (e.g. Leucht et al (2013) and Tyrer and Kendall (2008)) have questioned whether the distinction between typical and atypical antipsychotics is a meaningful one.

- Side effects: All antipsychotics carry a risk of side effects to varying degrees. These side effects can range from mild (e.g. weight gain, dizziness) to potentially fatal (e.g. heart attack, stroke, neuroleptic malignant syndrome). Lieberman et al (2005) found that 74% of 1,342 schizophrenic patients discontinued antipsychotic drug treatment within 18 months due to side effects.

Psychological approach to schizophrenia

Psychological explanations of schizophrenia

Psychological explanations of schizophrenia include family dysfunction and cognitive explanations (e.g. dysfunctional thought processing).

Family dysfunction

Several psychologists have proposed that family dysfunction (e.g. high levels of conflict or difficulties communicating) can influence the development of schizophrenia.

One example of this is Bateson et al (1956), who proposed the double bind explanation of schizophrenia. According to this explanation, children who often get conflicting messages from their parents are more likely to develop schizophrenia. For example, a mother who loves her child but has trouble expressing it may exhibit contradictory behaviours (e.g. hugging the child but being critical with her words). Another example is a parent who tells their child to be more spontaneous: Whatever the child does, they can’t fulfil this request because if they do act more spontaneous because their parent tells them then they aren’t acting spontaneously! Constant exposure to these mixed messages and impossible demands mean the child is unable to form a coherent picture of reality. This leads to disorganised thinking which in extreme cases can manifest as symptoms of schizophrenia such as delusions and hallucinations.

Another familial explanation of schizophrenia is expressed emotion. An environment with a high degree of expressed emotion – particularly negative, such as criticism and hostility – causes stress, which increases the risk of schizophrenia. Expressed emotion is primarily associated with relapse in schizophrenic patients.

AO3 evaluation points: Family dysfunction explanation of schizophrenia

Strengths of the family dysfunction explanation:

- Evidence supporting the family dysfunction explanation: Adoption studies suggest that dysfunctional family environments increase the risk of schizophrenia. For example, in a follow-up to their longitudinal study described above, Tienari et al (2004) rated familial dysfunctionality among the adoptive environments of adoptees whose biological mothers had schizophrenia. They found that adoptees raised in families rated as dysfunctional had much higher rates of schizophrenia (36.8%) compared to adoptees raised in families rated as healthy (5.8%).

- Evidence supporting the role of expressed emotion: A meta-analysis of 26 studies by Butzlaff and Hooley (1998) found relapse rates are higher among schizophrenic patients who return to live with families with a high degree of expressed emotion. The role of expressed emotion in schizophrenia is further supported by the success of family therapies that aim to reduce expressed emotion. However, this research doesn’t support expressed emotion as a cause of schizophrenia, but it does suggest it contributes to maintaining schizophrenia.

Weaknesses of the family dysfunction explanation:

- Exceptions: Not everyone raised in a dysfunctional family goes on to develop schizophrenia, and not everyone with schizophrenia was raised in a dysfunctional family. This suggests that other factors are important in explaining schizophrenia, such as biology.

- Correlation vs. causation: Even if schizophrenia is correlated with family dysfunction, this doesn’t prove that family dysfunction causes schizophrenia – it could be the other way round. For example, it seems possible that having a schizophrenic family member could itself cause stress and dysfunction within the family, rather than that family dysfunction causes schizophrenia. It’s a chicken or egg scenario: Which comes first?

- Methodological concerns: Bateson et al’s double bind explanation of schizophrenia is based on a handful of case studies and interviews. Some critics have suggested researchers focus on examples that support the explanation while ignoring examples that conflict with it (selection bias).

Cognitive explanations

Cognitive explanations of schizophrenia look at how schizophrenic patients think and process information. Schizophrenic cognition may differ from non-schizophrenic cognition in several ways:

- Dysfunctional thought processing: Metacognition is the ability to think about and reflect on one’s own thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. Schizophrenic patients are seen as suffering from metacognitive dysfunction, which may explain some symptoms of schizophrenia such as hallucinations. For example, an inability of schizophrenic patients to recognise their thoughts as their own may explain hearing voices: The patient attributes their own thoughts to some external source outside their mind.

- Cognitive biases: Positive symptoms of schizophrenia, such as delusions, can be explained as a result of cognitive biases. For example, bias may mean a schizophrenic person interprets the ordinary actions of other people as sinister, supporting their delusion that they are a victim of a conspiracy or that people are trying to harm them.

- Cognitive deficits: Bowie and Harvey (2006) describe various cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia, such as:

- Attention deficits: Schizophrenic patients often have difficulty concentrating and paying attention.

- Speech deficits: Schizophrenic patients often have low verbal fluency and difficulty finding words. This may explain the symptom of speech poverty.

- Memory deficits: Schizophrenic patients often have impaired working memory, particularly verbal working memory.

AO3 evaluation points: Cognitive explanations of schizophrenia

Strengths of cognitive explanations:

- Evidence supporting cognitive explanations: Several studies have found evidence of cognitive impairment in schizophrenic patients. Bowie and Harvey’s (2006) review above cites many examples. Cognitive impairments are often present before the patient’s first schizophrenic episode and persist throughout the disorder, but therapies that reduce cognitive impairment (e.g. CBT) often improve schizophrenia symptoms. This all supports a role for cognitive explanations of schizophrenia.

- Practical applications: Cognitive explanations have been used to develop effective therapies for treating schizophrenia, such as CBT.

- Complements other explanations: Cognitive explanations can be combined with other explanations (e.g. biological) to give a more holistic account of schizophrenia.

Weaknesses of cognitive explanations:

- Evidence against cognitive explanations: Many people have the cognitive biases and cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia (for example, as a result of brain damage) and yet do not develop schizophrenia. This suggests that cognitive explanations alone are too reductionist: There is more to explaining schizophrenia than just cognitive explanations.

- Does not explain the cause of schizophrenia: Cognitive theories simply describe the thought processes of schizophrenia but do not explain why people with schizophrenia have these thought processes in the first place.

Psychological treatment of schizophrenia

In addition to antipsychotic drugs, various psychological treatments for schizophrenia exist such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), family therapy, and the use of token economies.

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the main psychological treatment for schizophrenia. There are many different forms of CBT, but the main aim is to help patients identify and challenge the irrational and maladaptive thoughts underlying schizophrenia.

For example, a schizophrenic patient may have delusional thoughts that there is a conspiracy to kill them. These thoughts cause negative emotions (e.g. fear, anxiety) and irrational behaviours (e.g. hiding from or attacking people).

For example, a schizophrenic patient may have delusional thoughts that there is a conspiracy to kill them. These thoughts cause negative emotions (e.g. fear, anxiety) and irrational behaviours (e.g. hiding from or attacking people).

CBT involves talking through irrational thoughts like this. The patient is encouraged to describe their thoughts to the therapist. The therapist then helps the patient identify and challenge the reality of these thoughts. For example, the therapist may ask the patient to consider how likely these thoughts are to be true and consider alternative explanations. The therapist may also help the patient tackle their symptoms from the behavioural angle (e.g. by teaching behavioural coping skills) and the emotional angle (e.g. by teaching relaxation techniques).

CBT is primarily used to treat positive symptoms of schizophrenia and is commonly used in combination with antipsychotic drug therapy. A typical course of CBT for schizophrenia might consist of 12 sessions spaced 10 days apart.

AO3 evaluation points: CBT for schizophrenia

Strengths of CBT for schizophrenia:

- Evidence supporting efficacy of CBT: Several studies have shown that CBT effectively reduces schizophrenia symptoms. For example, a meta-analysis of 14 studies involving 1,484 schizophrenia patients by Zimmermann et al (2005) found CBT significantly reduced positive symptoms of the disorder.

- Complements other treatments: CBT can be used in conjunction with other treatments, such as antipsychotic drugs. Some evidence suggests this combined therapy is more effective than antipsychotic drugs or CBT alone.

- Less side effects than antipsychotic drugs: CBT has very few side effects. By comparison, antipsychotic drugs carry a risk of serious and potentially fatal side effects such as pyramidal symptoms, increased risk of heart attack, and weight gain.

Weaknesses of CBT for schizophrenia:

- Conflicting evidence: Contrary to Zimmerman et al (2005), a meta-analysis by Jauhar et al (2014) found CBT only had minor effects on schizophrenia symptoms. Further, when the researchers looked at blinded studies only (i.e. studies where the researchers were not aware which patients received CBT and which didn’t), even this small effect size disappeared. This calls into question the efficacy of CBT and suggests that research supporting the efficacy of CBT for schizophrenia may simply be the result of researcher bias.

- Not suitable for all patients: An important aspect of CBT is developing a trusting alliance between patient and therapist. However, some schizophrenic patients may be too paranoid or anxious to develop such a trusting alliance and so are not suitable candidates for CBT.

Family therapy

Family therapy is a treatment for schizophrenia based on the family dysfunction explanation of schizophrenia. According to this explanation, schizophrenia is caused (at least in part) by familial dysfunction and so family therapy aims to address this dysfunction rather than focusing on the schizophrenic patient in isolation. This involves talking openly about the patient’s illness and how it affects them with an aim to:

- Improve communication patterns: Increase positive communication and decrease negative communication among the family (i.e. reduce levels of expressed emotion)

- Increase tolerance and understanding: Educate family members about schizophrenia and how to deal with it (e.g. how to support each other)

- Reduce feelings of guilt and anger: Family members may feel guilty (e.g. that they are responsible for causing schizophrenia) or angry towards the schizophrenic patient

A typical course of family therapy may consist of weekly sessions for a year, after which the family members will have developed skills that they can use after therapy has ended.

AO3 evaluation points: Family therapy for schizophrenia

Strengths of family therapy for schizophrenia:

- Evidence supporting efficacy of family therapy: Several studies have demonstrated lower rates of schizophrenia relapse among patients receiving family therapy. For example, a meta-analysis by Pilling et al (2002) looked at 18 studies of family therapy for schizophrenia and found that it had a clear effect on reducing relapse rates.

- Complements other treatments: Evidence suggests that family therapy plus antipsychotic drug therapy is more effective at reducing relapse than antipsychotic drug therapy alone. For example, Xiong et al (1994) randomly allocated 63 subjects to either a drug therapy group or a drug therapy plus family therapy group. After one year, relapse rates were lower in the drug therapy plus family therapy group (33%) compared to the drug therapy only group (61%).

- Less side effects: Family therapy has very few (if any) side effects relative to antipsychotic drugs.

- Cost effective: The Schizophrenia Commission (2012) estimate that family therapy results in cost savings of around £1000 per patient over a 3 year period.

Weaknesses of family therapy for schizophrenia:

- Could be counterproductive: Family therapy for schizophrenia emphasises being open and honest. However, in some families, open communication may reveal difficult truths or reignite old arguments. This could increase, rather than decrease, negative communication and potentially make the problem worse.

- Not suitable for all patients: Some schizophrenic patients do not have dysfunctional families and so family therapy is unlikely to be an effective treatment for them.

Token economies

Token economies is a behaviourist approach to schizophrenia based on operant conditioning: Schizophrenic patients are awarded tokens (that can be exchanged for rewards) in return for desirable behaviour.

Token economies is a behaviourist approach to schizophrenia based on operant conditioning: Schizophrenic patients are awarded tokens (that can be exchanged for rewards) in return for desirable behaviour.

Token economies are mainly used to treat negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as avolition. For example, avolition may mean the patient has little motivation to undertake tasks such as getting out of bed, washing, and socialising. Token economies provide an incentive for the patient to undertake these tasks, changing their behaviour.

Token economies are primarily used for schizophrenic patients who are in institutions for long time periods. As well as schizophrenia, token economies are also used to deal with criminal behaviour (see the forensic psychology page for more details).

AO3 evaluation points: Token economies for schizophrenia

Strengths of token economies:

- Evidence supporting efficacy of token economies: Several studies suggest token economies can improve symptoms of schizophrenia. For example, a review of studies by McMonagle and Sultana (2000) found token economies reduced the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. However, the researchers note that the evidence is not conclusive, with questions about the replicability of the findings and uncertainty about whether behavioural changes can be maintained after the treatment ends.

- Complements other treatments: Token economies can be used in conjunction with other treatments, such as antipsychotic drugs.

Weaknesses of token economies:

- Ethical concerns: Use of token economies could be seen as unethical for several reasons. Firstly, some argue that token economies are dehumanising as they take away the patient’s rights to make their own choices. Secondly, some argue that token economies are discriminatory: Severely ill patients will have greater difficulty complying with behavioural demands and thus get fewer privileges than patients who are less severely ill. Token economies may thus discriminate against the most severely ill patients.

- Relapse: If improvements in behaviour are dependent on receiving tokens, the schizophrenic patient may relapse once token economy therapy is withdrawn.

Interactionist approach to schizophrenia

Rather than trying to reduce schizophrenia to either a psychological or biological phenomena, interactionist approaches to schizophrenia explain the disorder as a combination of various factors. One example of this is the diathesis-stress model.

Diathesis-stress model

The diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia explains the disorder as a combination of genetic and environmental factors. According to this model, biology determines a person’s vulnerability to schizophrenia (biological diathesis), but schizophrenia is only triggered in response to environmental stressors (stress).

So, a person with a high genetic predisposition towards schizophrenia may never develop the disorder (e.g. if they live in a supportive low-stress environment) but a person with a lower genetic disposition may develop schizophrenia if exposed to enough environmental stress (e.g. dysfunctional family upbringing, drug abuse, etc.). In other words, genetic disposition is necessary to developing schizophrenia, but not sufficient by itself.

The diathesis-stress model originated with Meehl (1962), who proposed the existence of a single ‘schizogene’ – the effects of which are activated in response to stress. However, more recent research (e.g. Ripke et al (2014)) suggests multiple genes contribute to genetic risk for schizophrenia. Also, ‘stress’ in the diathesis-stress model is not just the emotion – it includes anything that increases the risk of triggering schizophrenia (e.g. drug use, illness, physical trauma, sexual abuse).

AO3 evaluation points: Diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia

Strengths of diathesis-stress model:

- Evidence supporting diathesis-stress model: There is strong evidence for both the genetic and environmental components of schizophrenia. For example, Gottesman’s family studies described above support a role for genetics but schizophrenia concordance rates among identical twins are much less than 100%, demonstrating environmental plays a role too. With regards to the diathesis-stress model specifically, several studies suggest that stress is a key environmental component. For example, a review by Walker et al (2008) found schizophrenia is associated with elevated baseline stress hormones (e.g. cortisol) and that drugs that increase stress hormones worsen schizophrenia symptoms. Further, a meta-analysis by Varese et al (2012) found that stressful events in childhood increase the risk of schizophrenia, further supporting the hypothesis that stress is a key trigger of schizophrenia in those genetically prone.

- Holistic: Rather than reducing schizophrenia to one single cause, the diathesis-stress model accounts for the multitude of factors that contribute to the disorder. This can be seen as a more complete picture of schizophrenia.

Weaknesses of diathesis-stress model:

- Incomplete: Although there is strong evidence supporting the role of both biological diathesis and stress in the development of schizophrenia, the mechanisms through which they cause schizophrenia are not clear.

Interactionist treatment of schizophrenia

Interactionist treatment approaches to schizophrenia tackle the disorder from multiple angles.

For example, a patient may be given antipsychotic drug therapy (a biological approach to treatment) in combination with cognitive behavioural therapy (a psychological approach to treatment). In general, research suggests such interactionist approaches are more effective than either treatment in isolation.

AO3 evaluation points: Interactionist treatment of schizophrenia

Although interactionist treatment approaches seem to be most effective, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. For example, family therapy will be more beneficial to a schizophrenic patient who was raised in a dysfunctional family environment, and the most suitable antipsychotic drug therapy for each patient will vary depending on efficacy and side effects. Costs are another factor to consider: It might not be economically viable to provide all schizophrenic patients with every possible treatment option.

Strengths of interactionist treatment approaches:

- Evidence supporting interactionist treatment approaches: Several studies suggest combination therapy is more effective than monotherapy. For example, Xiong et al (1994) randomly allocated 63 schizophrenic patients to either a drug therapy group or a drug therapy plus family therapy group. After one year, relapse rates were lower in the drug therapy plus family therapy group (33%) compared to the drug therapy only group (61%). These findings are supported by a study of 103 schizophrenic patients conducted by Hogarty et al (1986), who reported relapse rates of 19% among patients treated with drug therapy plus family therapy compared to 41% for patients treated with drug therapy alone. Further, Sudak (2011) describes how cognitive behavioural therapy makes patients more likely to adhere to drug therapy because it helps the patient rationally understand the benefits of doing so. This suggests antipsychotic drug therapy plus cognitive behavioural therapy will be more effective than drug therapy alone.

- Holistic: There are both biological and psychological components to schizophrenia, but interactionist approaches treat both. This is a more complete approach to treatment, which might explain why interactionist approaches are more effective. For example, antipsychotic drugs may address the chemical imbalances of schizophrenia while cognitive behavioural therapy addresses the irrational thought processes.

Weaknesses of interactionist treatment approaches:

- Increased costs: Interactionist treatment approaches will be more expensive than monotherapy because you have to pay for multiple treatments (e.g. CBT, family therapy, and antipsychotic drugs) rather than just one. However, if interactionist treatment approaches lead to lower relapse rates than monotherapy, this may save money in the long run because it prevents further costs to the health service down the line.

- Conflicting evidence: Some studies raise questions as to whether some interactionist approaches to therapy really are more effective than monotherapy. For example, Jauhur’s meta analysis described in the AO3 points for CBT above questions whether CBT really is an effective treatment for schizophrenia. If CBT is not an effective treatment for schizophrenia, then CBT+antipsychotic drug therapy is unlikely to be any more effective than antipsychotic drug therapy alone.

<<<Relationships

or:

<<<Gender

or:

<<<Cognition and development

Aggression>>>

or:

Forensic psychology>>>

or: