Overview – Aggression

Aggression is hostile behaviour that is intended to cause physical or psychological harm. This A level psychology topic looks at the psychology underlying aggression, including:

- Biological mechanisms involved in aggression (including genetic, neural, and hormonal factors)

- Ethological explanations of aggression (including innate releasing mechanisms and fixed action patterns)

- Evolutionary explanations of human aggression

- Social and psychological explanations of aggression (including the frustration-aggression hypothesis, social learning theory, and de-individuation)

- Institutional aggression in prisons (including dispositional and situational explanations)

- Media influences on aggression (effects of which include desensitisation, disinhibition, and cognitive priming)

Biological mechanisms of aggression

Biological mechanisms of aggression include neural mechanisms, hormones, and genetics.

Neural mechanisms

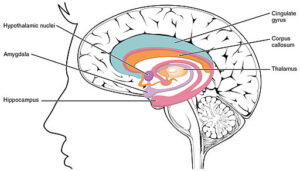

Neural mechanisms (i.e. mechanisms of the nervous system) play a role in aggression. These include the limbic system of the brain and the neurotransmitter serotonin.

Limbic system

The limbic system is an area of the brain that plays a key role in emotional processing and is the main area of the brain associated with aggression.

The limbic system is an area of the brain that plays a key role in emotional processing and is the main area of the brain associated with aggression.

In particular, the amygdala (an area of the limbic system) is associated with aggression.

- Gospic et al (2011) used fMRI brain scans to measure brain activity during a game designed to provoke aggression. Aggressive responses were correlated with increased activity in the amygdala. Further, participants who were given drugs that reduced amygdala activity were less aggressive.

- Brain scans of convicted murderers by Raine et al (1997) found abnormalities in the amygdala (and other areas of the limbic system) compared to controls, which suggests their aggressive crimes may be partly explained by these abnormalities.

- Sumer et al (2007) describe a case study of a girl who suffered from epileptic fits and displayed aggressive behaviour. Brain scans revealed she had a tumour in her limbic system. Doctors treated the tumour with drugs, which stopped both the seizures and aggressive behaviours.

AO3 evaluation points: Limbic system and aggression

- Supporting evidence: There is a lot of evidence supporting the neural explanations of aggression (see studies above) but the exact role of the limbic system is still somewhat unclear.

- Correlation vs. causation: Although there are correlations between aggressive behaviour and limbic system abnormalities, this does not necessarily prove that limbic system abnormalities cause aggressive behaviour. For example, there are people with limbic system abnormalities who are not overly aggressive, and there are aggressive people with normal limbic systems.

- Deterministic: Neural explanations of aggression are deterministic. If aggressive behaviour is explained solely in terms of neural processes, then it leaves no room for the free will of the individual and means people are not in control of their behaviour. This implies people are not morally responsible for aggressive behaviour (as it is not freely chosen).

Serotonin

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter (see the biopsychology page for more details) associated with aggression. Some studies suggest low serotonin levels increase aggression and that higher serotonin levels decrease aggression. For example:

- Virkkunen et al (1994) found that impulsive violent offenders in Finnish prisons had lower serotonin levels (as measured by 5-HIAA levels, a serotonin metabolite) compared to controls.

- Berman et al (2009) randomly assigned 80 subjects (40 with a history of aggression, 40 without) to receive either a drug that increases serotonin activity (paroxetine) or placebo. Among participants with a history of aggression, those who had been given paroxetine behaved less aggressively than those given placebo (as measured by the severity and frequency of electric shocks when playing a game).

- Cherek and Lane (1999) also found that giving subjects a drug that increases serotonin activity (d, l-fenfluramine) reduced their aggressive behaviour.

AO3 evaluation points: Serotonin and aggression

- Supporting evidence: The studies above support the hypothesis that low serotonin increases aggression.

- Questions of external validity: The findings of the studies above may not apply to the general population in everyday life. For example, Berman et al (2009) and Cherek and Lane (1999) based their conclusions on games played in laboratory conditions, which may not reflect behaviours in real life. Similarly, many studies (e.g. Virkkunen et al (1994)) use criminal convictions as a measure of aggression, but this may not be an accurate measure of aggressive behaviour in the general population.

- Conflicting evidence: The exact role of serotonin in aggression is somewhat unclear, as research can be conflicting. For example, Huber et al (1997) demonstrated that injecting crayfish with serotonin made them behave more aggressively rather than less (although as an animal study these findings may not be valid when applied to humans).

- Correlation vs. causation: Even if low serotonin and aggressive behaviour are correlated, it does not automatically prove that low serotonin causes aggressive behaviour. For example, serotonin could decrease in response to angry feelings, in which case it could be an effect of aggression rather than a cause.

Hormonal mechanisms

Hormones are chemicals produced in the body by glands (see the biopsychology page for more details). The main hormone the syllabus focuses on for aggression is testosterone.

Testosterone

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone in males and is linked with aggression. Several studies have found that high testosterone is correlated with increased aggression and that low testosterone is correlated with decreased aggression. For example:

- Albert et al (1989) found that injecting female rats with testosterone made them behave more aggressively.

- Van Goozen et al (1995) found that administering testosterone to female-to-male transgender people resulted in more aggressive behaviour. Conversely, male-to-female transgender people given drugs to lower their testosterone levels behaved less aggressively.

- Dabbs et al (1995) studied testosterone levels of prisoners. Offenders who had committed violent crimes had higher testosterone levels and were more likely to be involved in fights than those who were convicted of non-violent crimes.

AO3 evaluation points: Hormonal mechanisms of aggression

- Supporting evidence: The studies above suggest a positive correlation between testosterone and aggression.

- Conflicting evidence: Although there is a lot of evidence supporting a link between testosterone and aggression, not all studies agree. For example, Tricker et al (1996) randomly assigned 43 men to receive either 600mg of testosterone per week or placebo but observed no differences in aggression between the two groups.

- Correlation vs. causation: Dabbs et al (1995) only shows that high testosterone levels are correlated with aggression, not that high testosterone causes aggression. However, Van Goozen et al (1995) and Albert et al (1989) suggest the link is causal and not simply correlational because increasing testosterone levels resulted in a direct increase in aggressive behaviour.

Genetics

Genetics are an important biological mechanism of aggression that may tie in with other biological factors. For example, a person may have genetics that predispose them to low serotonin activity, or genetics that encode for limbic system abnormalities.

Twin studies

As always, twin studies are a useful way to determine the extent to which a behaviour or psychological condition is genetic. If concordance rates of aggression are higher among identical twins (who share 100% of their genes) than non-identical twins (who only share 50% of their genes), this shows that genetics play a role.

- Coccaro et al (1997) analysed data from 182 pairs of identical twins and 118 pairs of non-identical twins. The concordance rate for physical violence was 50% among identical twins and 19% among non-identical twins.

- Christiansen (1977) analysed the concordance rates for criminal convictions (a proxy for aggression) among 3,586 pairs of twins. Among males, concordance rates were 35% for identical twins and 12% for non-identical twins. Among females, the concordance rates were 21% for identical twins and 8% for non-identical twins.

The higher concordance rates for aggression and criminality among identical twins than non-identical twins suggests there is a genetic component to aggression.

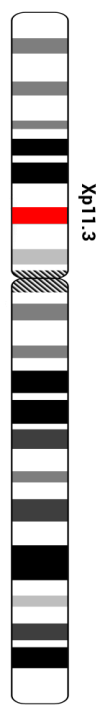

The MAOA gene

One gene in particular is associated with aggression, the MAOA gene.

One gene in particular is associated with aggression, the MAOA gene.

The MAOA gene is responsible for producing monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), which is an enzyme that processes neurotransmitters such as serotonin. The low-activity form of the gene (MAOA-L or the “warrior gene”) results in lower levels of MAOA and is associated with aggression.

The link between the MAOA gene and aggression was discovered by Brunner et al (1993) in a study of a family in the Netherlands. 5 members of this family had a history of impulsive aggression and crime and the researchers discovered that all 5 had dysfunctional MAOA genes, which resulted in an MAOA deficiency.

AO3 evaluation points: Genetic mechanisms of aggression

- Supporting evidence: Several studies in addition to Brunner et al (1993) have confirmed a correlation between the MAOA-L gene and aggression. For example, McDermott et al (2009) conducted an experiment where male subjects played a game where they were able to punish players who stole money from them. Subjects with the MAOA-L gene punished those who stole from them more aggressively than subjects without the MAOA-L gene (although only in situations where the other player stole a large amount from them).

- Exceptions: Many people with the MAOA-L gene are not overly aggressive, and many people are aggressive despite not having the MAOA-L gene.

- Other factors: If aggression was 100% genetic, concordance rates for aggression among identical twins would be 100%. However, the twin studies outlined above found concordance rates to be lower than 50% among identical twins, which suggests other factors besides genetics are important for aggression. Further, several studies (e.g. Caspi et al (2002) and Gallardo-Pujol et al (2012)) demonstrate that environmental factors interact with the MAOA gene to increase the likelihood of aggression.

- Deterministic: Genetic explanations of aggression are deterministic. If aggressive behaviour is explained solely in terms of genetics, then it leaves little room for free will and means people are not in control of their behaviour. This raises ethical issues as it implies people are not morally responsible for aggressive behaviour (as it is not freely chosen). This genetic argument was used in the 2009 US trial of Bradley Waldroup, who had the MAOA-L gene and was abused as a child. Waldroup avoided a first-degree murder conviction but was convicted of manslaughter and attempted second-degree murder.

Ethological explanations of aggression

Ethology is the study of natural animal behaviour. Studying aggression in animals provides insights into aggression in humans and helps inform evolutionary explanations of human aggression.

Lorenz (1966) argued that aggressive behaviour is an innate (i.e. biologically pre-programmed) response that has evolved to help species survive and pass on their genes. He argued that aggression is a biological need like eating or drinking. In the same way that hunger continuously builds up until an animal eats food, innate releasing mechanisms mean aggression continuously builds up until the animal behaves aggressively and satisfies that need.

Patterns of aggressive behaviour within a species are often ritualistic. From an evolutionary perspective, it wouldn’t make sense for members of a species to try and actually kill each other every time they fight because then the species would go extinct. Instead, rituals enable members of a species to compete and establish dominance without actually harming each other. For example, a wolf who loses a fight exposes its neck to signal that it has lost. This position makes it easy for the winner to kill the loser but instead the fight ends there.

The typical pattern of aggressive behaviour for an animal is as follows:

- Aggression continuously builds up over time

- An environmental stimulus (e.g. another animal of the same species) triggers the innate releasing mechanism

- The innate releasing mechanism releases a fixed action pattern of behaviour

- Aggression is released and the cycle repeats

Innate releasing mechanisms

Innate releasing mechanisms are biologically hard-wired mechanisms for aggression (e.g. brain structures or neural pathways for aggression). Environmental cues (e.g. the red belly of a rival stickleback) trigger the innate releasing mechanism. This releases a fixed action pattern of behaviour.

Fixed action patterns

Aggressive behaviours within a species often follow set patterns known as fixed action patterns. These patterns are universal (i.e. the same) across the species and once they are initiated the animal will keep going until the behaviour is complete.

An example of a fixed action pattern can be seen in stickleback fish:

- During the mating season, male sticklebacks build nests where females lay eggs

- (Male sticklebacks also develop red bellies during this time)

- If another male enters their territory, the stickleback will attack it

Tinbergen (1952) demonstrates how fixed action patterns in sticklebacks are universal. When Tinbergen presented male sticklebacks with models of fish with red bellies (even when the model was not realistic looking), they all responded with the same fixed action pattern of fighting behaviour. The universal nature of this behaviour suggests the fixed action pattern is innate.

AO3 evaluation points: Ethological explanations of aggression

Strengths of ethological explanations:

- Evidence supporting ethological explanations: There are many examples of fixed action patterns in animals beyond Tinbergen (1952). For example, if an egg (or similar looking object) is placed near a Grelag goose, it will instinctively try to roll the egg into its nest in a fixed action pattern.

Weaknesses of ethological explanations:

- Questions of validity in humans: Animals like sticklebacks (or even higher primates like chimpanzees) are very different to humans and so explanations of aggression in these animals may not apply to humans. Further, human aggression is very different to animal aggression. For example, humans wage wars and have weapons like guns and nuclear bombs, which animals don’t.

- Conflicting evidence: Schleidt (1974) argues that ‘fixed’ action patterns are often quite varied. For this reason, some ethologists (e.g. Barlow (1968)) prefer the term modal action pattern.

- Exceptions: There are many examples of aggression in humans that don’t fit the pattern described by ethological explanations. For example, premeditated murder is the result of cognitive processes and timely consideration rather than a fixed action pattern as an immediate response to an environmental cue.

Evolutionary explanations of human aggression

Evolution is the process by which species adapt to their environment. Over many years, random mutations in genes that are advantageous (either in terms of survival or reproduction) become more widespread among the species. As well as physical characteristics, these genes may encode for certain behaviours such as aggression (e.g. fixed action patterns).

Survival advantages

Genes for aggression may humans help humans survive in the following ways:

- Gain access to resources: Aggression (physical or otherwise) may be an effective way to gain resources such as food or territory. Having resources like food, for example, mean you are less likely to starve to death.

- Defence: In addition to being a way to defend your resources, aggression also protects against injury and death. For example, if you don’t fight back when someone is aggressive with you, then they might keep going until they kill you.

If a human is more likely to survive, then they are more likely to live long enough to reproduce and pass on their genes.

Reproductive advantages

Genes for aggressive behaviour may also increase the likelihood that a human reproduces and passes on their genes. This is particularly true for men rather than women, for the following reasons:

- Competition for mates: Anisogamy (see the relationships page for more details) means women must be selective over who they have children with. As such, men compete with other men for status and resources so that women will choose them as a mate. Pinker (1997) argues that competing for women is the main reason aggression evolved in men.

- Deter infidelity: Anisogamy also means women can be certain of paternity (i.e. that their children are theirs) but men can’t. Raising another man’s child is evolutionarily disadvantageous and so men may have evolved aggression as a way to prevent women from cheating on them. Wilson and Daly (1996) identify two main strategies for this: Direct guarding (e.g. watching over their partner’s behaviour) and negative inducements (e.g. threats).

AO3 evaluation points: Evolutionary explanations of human aggression

Strengths of evolutionary explanations:

- Evidence supporting evolutionary explanations: Several studies support the evolutionary explanation of human aggression. For example:

- Competition for mates: Wilson and Daly (1985) looked at data from 690 murders in Detroit in 1972 and found the vast majority were committed by and perpetrated against young men – the most common reason being “status competition”. This fits with the evolutionary explanation that men evolved to be more aggressive in order to gain status and compete for females.

- Deter infidelity: From interviews with spouse-killers, Wilson and Daly (1988) found that “the husband’s proprietary concern with his wife’s fidelity or her intention to quit the marriage led him to initiate the violence in an overwhelming majority of cases”. This fits with the evolutionary explanation that men evolved to behave aggressively in order to prevent their partners cheating on them.

- Explanatory power: Men are generally more aggressive than women (see the gender page for more details). The evolutionary explanation can explain this in the following way:

- Why males are more aggressive: Aggression means males are more likely to win competitions for female mates and/or deter partner infidelity, which makes them more likely to pass on their genes.

- Why females are less aggressive: Children are highly dependent on their mothers for survival. Because of this, Campbell (1999) argues that aggression in women makes them less likely to pass on their genes because engaging in aggressive conflicts increases the likelihood that a mother will die before she can raise her child to independence.

Weaknesses of evolutionary explanations:

- Other factors: If aggression was 100% explained by evolution, you would expect aggressive behaviour to be uniform across the human species. However, there are significant differences in aggression between different cultures. For example, aggression among the !Kung people of the Kalahari desert results in loss of status, whereas aggression among the Yanomami people of South America is correlated with high status. These differences suggest that other factors – such as cultural influences – are needed for a complete explanation of human aggression.

- Methodological concerns: Evolutionary hypotheses are basically impossible to test because evolution takes so long to occur. We can’t run a controlled experiment over millions of years that compares genes for aggression vs. less aggressive genes to see which ones become more widespread. Instead, the evidence for evolutionary hypotheses is usually correlational – e.g. the correlation between strategies to deter infidelity and aggression suggests aggression would be evolutionarily advantageous. However, this correlation does not prove these evolutionary factors cause aggression.

- Deterministic: Evolutionary explanations of aggression are deterministic. If aggressive behaviour is explained solely in terms of evolution and genetics, then it leaves little room for free will and means people are not in control of their behaviour. This raises ethical issues as it means people are not morally responsible for aggressive behaviour because it is not freely chosen.

Social psychological explanations of aggression

Social psychological explanations of aggression explain aggression as a result of social interactions with the environment. These explanations include the frustration-aggression hypothesis, social learning theory, and de-individuation.

Frustration-aggression hypothesis

Dollard et al (1939) proposed the frustration-aggression hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, aggression is a response to frustration.

Frustration is defined as being prevented from achieving a goal. For example, if you’re trying to beat someone at tennis (your goal) but they keep beating you, this causes feelings of frustration. This frustration leads to aggression – either a feeling of aggression or actual aggressive behaviour. For example, if you get really frustrated, you might throw your racket at the other player.

Frustration is defined as being prevented from achieving a goal. For example, if you’re trying to beat someone at tennis (your goal) but they keep beating you, this causes feelings of frustration. This frustration leads to aggression – either a feeling of aggression or actual aggressive behaviour. For example, if you get really frustrated, you might throw your racket at the other player.

The likelihood of aggressive behaviour is proportional to the level of frustration; the more frustrated someone is, the more likely they are to act aggressively. For example, if a goal is really important to someone and something prevents them from achieving it, that person is more likely to get frustrated and behave aggressively than if it was a goal they didn’t care about.

Further, the possible consequences of aggressive behaviour increase or decrease the likelihood of aggression in response to frustration. For example:

- Punishment: If someone fears being punished for acting aggressively, they may displace their aggression onto something (or someone) else. If there is no punishment, the person is more likely to behave aggressively.

- Usefulness: Aggressive behaviour is less likely if it won’t help you achieve your goal. For example, smashing a tennis racket in anger is unlikely to help you win. However, if aggression may help achieve your goal, aggressive behaviour is more likely. For example, if you’re waiting for a pizza delivery, you may reason that phoning up the delivery driver and getting aggressive might make your pizza arrive more quickly.

AO3 evaluation points: Frustration-aggression hypothesis

Strengths of frustration-aggression hypothesis:

- Evidence supporting the frustration-aggression hypothesis: For example, Geen (1968) conducted an experiment where male subjects were frustrated while trying to complete a jigsaw puzzle. After the jigsaw, subjects were able to deliver an electric shock to a confederate. Participants in groups that had been frustrated delivered more intense electric shocks than those in the control (non-frustrated) group. In another study, Buss (1963) found that participants who were frustrated in 3 different ways all displayed more aggression than a control group, although the effect was slight.

Weaknesses of frustration-aggression hypothesis:

- Conflicting evidence: In a later study, Buss (1966) found no correlation between level of frustration and aggression, contradicting his earlier study (Buss (1963) above).

- Other factors: There are many instances where people behave aggressively without being frustrated. For example, a person who is threatened may attack (i.e. act aggressively) towards the threat because they feel afraid rather than frustrated. This suggests that other explanations besides frustration – e.g. biological mechanisms or alternative social psychological theories – are needed for a complete explanation of aggression.

- Methodological concerns: Much of the evidence supporting the frustration-aggression hypothesis comes from games conducted in laboratory conditions. As such, the frustration-aggression hypothesis may lack ecological validity when applied to real-life situations outside the lab.

Social learning theory

Social learning theory (see the approaches page for more details) explains behaviour, such as aggression, as the result of observation and imitation of role models.

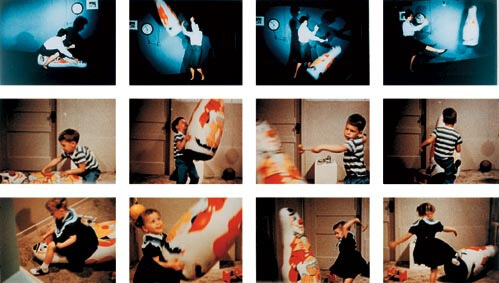

Bandura’s (1961) Bobo the doll experiment supports this explanation. A brief reminder of the experiment:

- Children aged 3-6 years old were observed interacting with an inflatable doll (Bobo)

- Beforehand, the children had been divided into 3 groups where they watched an adult role model interacting with Bobo the doll:

- Group 1: The role model behaved aggressively towards the doll (hitting it with a hammer and shouting abuse at it)

- Group 2: The role model did not behave aggressively towards the doll

- Group 3: No role model (control group)

- The children in group 1 (who had previously observed the aggressive role model) behaved more aggressively towards Bobo the doll

A complete social learning explanation of aggression will also reference mediating processes: The cognitive factors in between observation and imitation that determine whether someone decides to imitate a behaviour or not. For example, if someone observes the role model being rewarded for aggressive behaviour, this provides motivation to imitate that behaviour and makes aggression more likely. However, if the role model is punished for aggression, this provides motivation not to behave aggressively and makes it less likely. The other mediating processes are attention, retention, and reproduction.

Another key element of social learning theory that is relevant here is vicarious reinforcement. If a person sees the role model rewarded for behaving aggressively, they are more likely to imitate the aggressive behaviour.

AO3 evaluation points: Social learning explanation of aggression

Strengths of social learning explanations:

- Evidence supporting social learning explanations: The Bobo the doll experiment supports the social learning explanation of aggression. Children who observed an aggressive role model behaved more aggressively, which supports the social learning explanation that aggression is learned from observation and imitation of role models.

- Practical applications: If aggression is learned through observation and imitation of role models, then aggressive behaviour can be reduced by altering the role models and their behaviour. For example, aggressive role models in the media could be replaced with non-aggressive role models, or aggressive behaviour could be punished rather than rewarded to avoid vicarious reinforcement of aggression. This shows how social learning could be used to reduce aggressive behaviour.

Weaknesses of social learning explanations:

- Other factors: Although social learning theory is able to explain aggression in some situations, there are other situations where aggression is better explained in other ways. For example, a person who is threatened may act aggressively towards the threat in order to protect themself, not because they are imitating the behaviours of a role model. Similarly, a person who is extremely frustrated at losing a game may act aggressively because of their emotional state rather than because they are imitating a role model.

- Methodological concerns: Bandura’s Bobo the doll experiments were conducted in laboratory conditions and used a toy doll. However, it may be that in a real-life environment, the subjects would not imitate the aggressive behaviour – especially if it was against an actual human being rather than a doll. As such, social learning theory may lack ecological validity when applied to aggression in real-life situations.

De-individuation

De-individuation is when a person loses a sense of personal identity and personal responsibility. According to the de-individuation explanation, anonymity (e.g. by being part of a large crowd or wearing a disguise) makes a person more likely to behave aggressively.

Festinger et al (1952) coined the phrase de-individuation to describe a phenomenon where people in crowds lose their sense of personal identity and instead identify with the morals and beliefs of a group. This feeling of anonymity in the crowd means people who might ordinarily be polite and civil may act aggressively and violently. A classic example of this would be a football fan who gets swept up in the crowd and behaves violently.

Festinger et al (1952) coined the phrase de-individuation to describe a phenomenon where people in crowds lose their sense of personal identity and instead identify with the morals and beliefs of a group. This feeling of anonymity in the crowd means people who might ordinarily be polite and civil may act aggressively and violently. A classic example of this would be a football fan who gets swept up in the crowd and behaves violently.

In addition to anonymity in a crowd, anonymity in other ways may cause de-individuation. For example, Dodd (1985) got 203 students to anonymously describe what they would do if nobody could identify them or hold them responsible for their actions. 36% of the responses involved some form of antisocial behaviour, with the most common answer being to rob a bank.

AO3 evaluation points: De-individuation explanation of aggression

Strengths of de-individuation explanations:

- Evidence supporting de-individuation explanations: In addition to Dodd (1985) above, Zimbardo (1969) also shows how people behave more aggressively when de-individuated. Participants were randomly allocated to either an individuated group (where they wore name badges and were introduced to the other participants) or a de-individuated group (where they wore hoods over their heads and were not referred to by name) and completed a task where they could deliver electric shocks to a confederate. Participants in the de-individuated group delivered shocks for twice as long as participants in the individuated group.

- Explanatory power: De-individuation might explain why online abuse is so common; people feel more anonymous and de-individuated when they’re behind a screen.

- Practical applications: If the de-individuation explanation is correct, then aggressive behaviour can be reduced by implementing measures that increase individuation and reduce anonymity. For example, requiring people to use their real names on social media could reduce aggression online.

Weaknesses of de-individuation explanations:

- Conflicting evidence: Gergen et al (1973) found that de-individuation caused the opposite effect to aggression. Participants were put together in a dark room so they couldn’t see each other and told to do whatever they wanted. Rather than behaving aggressively, the participants would kiss and touch each other. This shows that de-individuation does not always cause increased aggression. Further, a meta-analysis of 60 studies by Postmes and Spears (1998) found the evidence for de-individuation explanations of aggression is weak.

- Other factors: Although de-individuation may explain aggression in specific contexts like crowds and social media, people often behave aggressively in situations where they are not de-individuated. This shows that other explanations (e.g. frustration, social learning, or biological factors) are needed for a complete explanation of aggression.

Institutional aggression (prisons)

Aggression in prisons is much higher than in ordinary contexts. There are two types of explanation for this increased aggression: Dispositional explanations and situational explanations.

Aggression in prisons is much higher than in ordinary contexts. There are two types of explanation for this increased aggression: Dispositional explanations and situational explanations.

Dispositional explanations

Dispositional explanations say that aggression is higher in prisons because people who get sent to prison are naturally more aggressive – that they have a disposition towards aggression.

The importation model is a dispositional explanation proposed by Irwin and Cressey (1962). According to the importation model, inmates import the social norms and behaviours of their criminal (and aggressive) lives outside of prison. These norms and behaviours make up 3 distinct subcultures within prisons:

- Thief subculture: Repeat offenders who are in and out of prison regularly. They follow a criminal code of honour that emphasises not snitching on other criminals/inmates, reliability, trustworthiness, and loyalty. Thieves follow the code and aim to do their time in prison and get out in the easiest way possible. The thief culture is more aggressive than the legitimate subculture but less aggressive than the convict subculture.

- Convict subculture: Typically offenders who are serving long sentences. People within the convict subculture aim to achieve status within the hierarchy of the prison and access to resources. The convict culture is the most aggressive as this is often an effective way to gain status and resources.

- Legitimate subculture: First-time offenders and people who don’t come from the criminal cultures of either the thieves or convicts. These people behave less aggressively than the other two groups and follow the legitimate prison rules (i.e. those set by the guards).

For whatever reason (biological factors, social factors, etc.), people from these subcultures have a disposition towards these behaviours – they act this way even when they aren’t in prison. And because these behaviours are more aggressive (at least within the thief and convict subcultures), these people are more likely to commit crimes and get arrested.

The importation model says aggressive behaviours are imported into the prison from the outside. In contrast, situational explanations say that aggression is a response to the internal conditions of the prison itself.

AO3 evaluation points: Dispositional explanations of aggression in prisons

In reality, both situational and dispositional explanations of institutional aggression are important. For example, Jiang and Fisher-Giorlando (2002) found that aggression towards prison staff was best explained by situational factors whereas aggression towards other inmates was best explained by the importation model. Rather than arguing that just one explanation being correct, you could take an interactionist approach.

Strengths of dispositional explanations:

- Evidence supporting dispositional explanations: DeLisi et al (2005) looked at the prison records of 831 US male inmates and found a strong correlation between gang membership and prison violence. This correlation supports the dispositional explanation that the increased aggression of gang members is imported into prisons.

Weaknesses of dispositional explanations:

- Other factors: The studies supporting situational explanations (see below) suggest that the deprived environment of prisons is at least partly responsible for the increased aggression in prisons.

Situational explanations

Situational explanations say that something about the environment of prisons makes people behave more aggressively – that the situation causes aggression.

The deprivation model is a situational explanation described by Sykes (1958). According to this model, inmates being deprived of the following 5 things causes aggression:

- Liberty: Prisoners are deprived of the freedom to go where they want. Sykes argues this reinforces feelings of being rejected by society, which makes prisoners more likely to feel and behave aggressively.

- Goods and services: Prisoners can’t access the goods and services they want. For example, you can’t just order takeaway or go on your phone like you might on the outside. This causes frustration and anger, which increases aggressive behaviour.

- Heterosexual relationships: Heterosexual prisoners do not have access to opposite-sex partners and so are deprived of sex and the emotional intimacy of romantic relationships. This again causes feelings of frustration, which may increase aggressive behaviour.

- Autonomy: The lives of prisoners are highly controlled – when they can go outside, when and what they eat, etc. is decided for them. This lack of control is frustrating and may lead to aggressive behaviour.

- Security: Prisons are violent environments and so prisoners do not feel safe. As such, prisoners are constantly on edge, which makes aggression and violence more likely.

Sykes calls these 5 deprivations the pains of imprisonment.

So, whereas dispositional explanations say prisoners are naturally more aggressive and import this aggression into the prison from the outside, the deprivation model blames the internal conditions of the prison for causing aggression.

AO3 evaluation points: Situational explanations of aggression in prisons

In reality, both situational and dispositional explanations of institutional aggression are important. For example, Jiang and Fisher-Giorlando (2002) found that aggression towards prison staff was best explained by situational factors whereas aggression towards other inmates was best explained by the importation model. Rather than arguing that just one explanation being correct, you could take an interactionist approach.

Strengths of situational explanations:

- Evidence supporting situational explanations: Some studies suggest situational factors increase aggression in prisons. For example, Megargee (1977) found that disruptive behaviour was highly correlated with crowding within prisons.

Weaknesses of situational explanations:

- Conflicting evidence: Camp and Gaes (2005) analysed data from 561 US male prisoners, who were randomly allocated to either a low-security California prison or a high-security California prison. Despite the differing prison environments, there was no significant difference in aggression between the two groups, which weakens support for situational explanations.

- Other factors: The studies supporting dispositional explanations (see above) suggest that aggressive behaviour is – to some extent – imported into prisons rather than a reaction to deprivation in the prison environment.

Media influences on aggression (video games)

The media may cause people to act more aggressively. The syllabus focuses specifically on the influence of video games, which may cause desensitisation, disinhibition, and cognitive priming.

The media may cause people to act more aggressively. The syllabus focuses specifically on the influence of video games, which may cause desensitisation, disinhibition, and cognitive priming.

Desensitisation

The natural reaction to aggression and violence is anxiety. But repeated exposure to such stimuli may reduce this emotional response – a person becomes desensitised to violence and aggression.

For example, a young child may be disturbed when they see somebody killed in a movie for the first time. But as an adult, the same sort of film does not provoke the same reaction because they’ve seen such depictions of violence many times and are now desensitised to it.

In theory, desensitisation increases aggression. Natural emotional reactions (e.g. anxiety, stress, revulsion, etc.) that would normally prevent a person from being violent are no longer as strong as they once were and so the person is more likely to behave aggressively.

Disinhibition

Inhibitions restrain us from behaving aggressively or inappropriately in real life. But within a video game, a person’s behaviour is disinhibited: They are free to act without consequence in ways they wouldn’t act in real life.

For example, you wouldn’t randomly attack a person on the street. But when playing a video game there are no real consequences for doing so – the character can’t actually fight back, you can’t actually get arrested, and there is no social penalty. Things that inhibit aggressive behaviour are not present in video games.

In theory, disinhibition when playing video games can transfer to real life. Inhibitions that would normally prevent someone from behaving aggressively are worn down so that behaviours that were once considered morally unacceptable now seem more acceptable. This may make a person more likely to behave aggressively in real life.

Cognitive priming

Cognitive priming is the idea that aggressive behaviours seen in the media are remembered and thus ‘prime’ a person to behave similarly when in similar situations. We absorb certain scripts for behaviour from media influences, and play out these scripts in similar situations.

For example, a man who watches a drama where a husband and wife argue over a comment made during dinner may remember and on some level learn this behaviour. If the man’s wife makes a negative comment during dinner one day, this memory primes him to argue with her like he saw in the drama.

In theory, exposure to violence and aggression in video games and the media can prime people to behave more aggressively in real life.

AO3 evaluation points: Media (video games) influence on aggression

- Evidence suggesting video games do increase aggression: A meta-analysis of 136 studies across multiple cultures by Anderson et al (2010) found that exposure to violent video games is correlated with increases in aggressive behaviour and aggressive thoughts.

- However, as always, correlation does not necessarily prove causation. It could be, for example, that when people are feeling aggressive they seek out video games as a source of catharsis, in which case the direction of causation would go in the opposite direction.

- Evidence supporting desensitisation specifically: Krahé et al (2011) measured participants’ skin conductance response (a measure of stress) as they watched a violent video clip. Participants who regularly watched violent films or played violent video games (as determined by questionnaire) demonstrated lower levels of stress when watching the violent video clip compared to those who didn’t, suggesting they were desensitised.

- However, even though supports a link between exposure to violent media and desensitisation, it does not necessarily prove the further claim that desensitisation increases aggressive behaviour.

<<<Schizophrenia

or:

<<<Eating behaviour

or: