Overview – Approaches in Psychology

There are multiple different ways to approach the study of psychology. For example, a biological approach might explain depression as a chemical imbalance, a cognitive approach might explain it in terms of maladaptive thought processes, and learning approaches might explain it as a result of negative life experiences.

A level psychology looks at the following psychological approaches:

- Learning approaches (behaviourism and social learning theory): Behaviour is learned from experience

- The cognitive approach: Behaviour is a result of thoughts and cognitive processes

- The biological approach: Behaviour is a result of biological processes

- The psychodynamic approach: Behaviour is a result of unconscious processes and unconscious conflicts

- Humanistic psychology: Behaviour is influenced by all these things, but each person ultimately has free will to decide their actions

Note: A level students need to understand the basic assumptions of these 5 approaches and be able to evaluate and compare them with one another. AS students only need to learn the basic assumptions of the first 3, and are not required to compare these approaches.

The topic also includes details on the origins of psychology.

Practice papers with A* answers book #2 contains five full exam papers with five approaches in psychology sections. These questions are closely based on the format of the AQA papers and are designed to be possible questions that could come up in the 2023 exam.

Practice papers with A* answers book #2 contains five full exam papers with five approaches in psychology sections. These questions are closely based on the format of the AQA papers and are designed to be possible questions that could come up in the 2023 exam.

Origins of psychology

Wilhelm Wundt: Introspection

Humans have studied the mind in some sense for thousands of years (e.g. philosophers, theologians, scientists). But the dedicated study of psychology – as we know it today – only started taking form in the late 19th Century with Wilhelm Wundt.

Humans have studied the mind in some sense for thousands of years (e.g. philosophers, theologians, scientists). But the dedicated study of psychology – as we know it today – only started taking form in the late 19th Century with Wilhelm Wundt.

Wundt founded the first psychology laboratory – the Institute of Experimental Psychology – in 1879 and is often called the ‘father of experimental psychology’. As part of his experiments, Wundt pioneered the technique of introspection. Introspection involves looking ‘inward’ and examining one’s thoughts, emotions, and sensations. For example, an experiment might involve showing subjects a picture, and the subjects would then report back their inner experiences.

For Wundt, introspection was not about reporting whatever random thing the subject felt. It was intended as a highly systematic and controlled process – a science. Wundt carefully controlled the environments and researchers were trained to adopt the right mental state and then report back the specific data Wundt wanted. Despite this rigour, Wundt often found that reports were highly subjective and varied from person to person, which meant they were unreliable.

AO3 evaluation points: Wundt's research

Strengths of Wundt’s role in psychology:

- Scientific: Wundt tried to apply the scientific method to his studies. For example, controlling the environment where he conducted his introspection experiments would prevent this extraneous variable from skewing the results. Further, training subjects to adopt the same state of mind and report back specific data should, in theory, produce more reliable results.

- Influential: Introspection and Wundt’s focus on the importance of inner mental processes can be seen to have influenced the cognitive approach to psychology.

Weaknesses of Wundt’s role in psychology:

- Unscientific: Despite Wundt’s attempts to study the mind scientifically, his research can be considered unscientific in many ways. Science is about what is objective, measurable, and repeatable but the private thoughts examined during introspection are subjective and can’t be measured. As such, Wundt was unable to replicate his findings. Because of this, Wundt’s research can be said to be unreliable and unscientific.

Emergence of psychology as a science

Since Wundt, a variety of approaches to psychology have emerged – some more ‘scientific’ than others.

Science is concerned with empirically observable facts that can be repeated and measured. For example, by repeatedly observing and measuring objects falling to the ground, scientists can deduce the laws that govern these observations (e.g. gravity). In theory, the science of psychology would observe human behaviour and deduce the laws that govern it in a similar way.

However, human behaviour is much less consistent than stuff like gravitation – people don’t always behave in the same ways or for the same reasons. This subjective dimension has led to various different approaches to the study of psychology, which developed along the following rough timeline:

- Behaviourism emerged in the early 20th century and remained the dominant approach to psychology until the 1950s. It rejected Wundt’s introspective approach as too subjective, instead focusing only on externally observable and measurable data – behaviour.

- The ‘cognitive revolution’ of the 1960s saw renewed interest in inner mental processes. Although thoughts and feelings are private and unobservable, the cognitive approach sought to make inferences about these inner mental processes from experiments.

- Advances in technology (particularly in the early 21st century) have progressively increased the power of a biological approach to psychology. For example, the discovery of fMRI brain scanning in 1990 enabled psychologists to measure brain activity and correlate it with mental processes. Elsewhere, advances in genome sequencing since the early 2000s have enabled psychologists to identify a genetic basis for some psychological disorders.

Learning approaches

Learning approaches measure and explain human behaviour as a product of environment and experience. The A level psychology syllabus specifies two learning approaches: behaviourism and social learning theory.

Behaviourist Approach

The behaviourist approach to psychology explains behaviour as a result of learning from experience, such as via classical and operant conditioning.

Basic assumptions

- The mind is a blank slate at birth and behaviour is learned from experience.

- The study of the mind should focus on external behaviour, not internal thought processes, as behaviour is the only thing that can be objectively measured and observed.

- The same processes that govern human behaviour also govern the behaviour of non-human animals (particularly mammals e.g. rats and dogs). As such, experiments on animal behaviour can yield valid conclusions about human behaviour too.

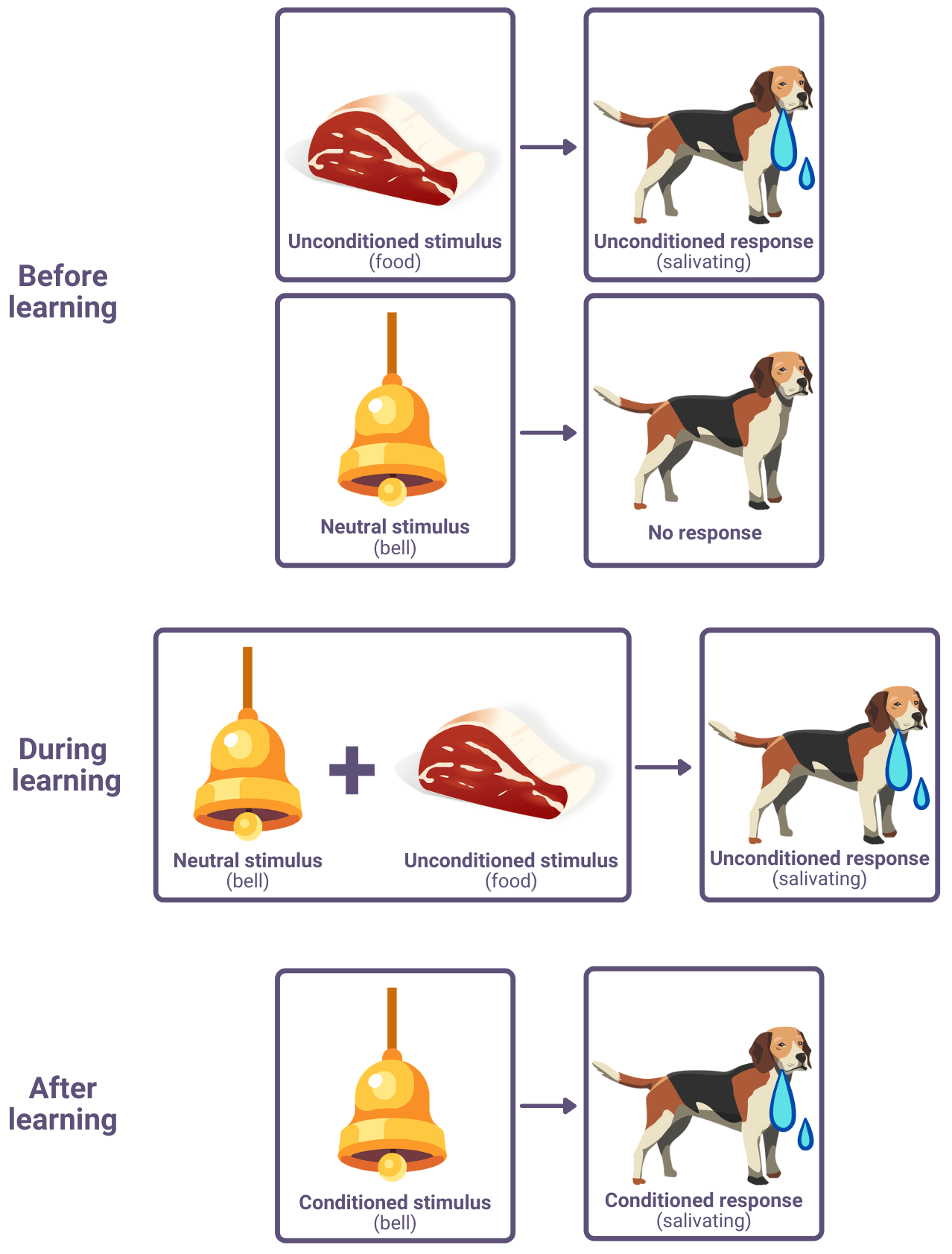

Ivan Pavlov: Classical conditioning

Classical conditioning is a key principle of behaviourism. It explains how behaviours are learned from experience via (subconscious) association.

The earliest and most famous documentation of classical conditioning is found in Pavlov (1927). Pavlov demonstrated how dogs could be conditioned to salivate (a natural response to food) in response to a bell ringing (a neutral stimulus) by ringing the bell at the same time as presenting the dog with food. The repeated occurrence of the bell ringing at the same time as the food meant the dogs learned to associate the bell with food. Eventually, this association produced a conditioned response in the dogs, who would salivate at the sound of the bell even when there was no food.

As mentioned, a basic assumption of behaviourism is the validity of animal studies in explaining human behaviour. And, in the case of classical conditioning, there are plenty of human examples like the one above. For example, hearing a phone notification go off (even if it’s someone else’s with the same tone) may cause you to instinctively reach into your pocket for your phone.

Other examples of classical conditioning in humans can be seen in the behaviourist explanation of phobias.

B.F. Skinner: Operant conditioning

Operant conditioning is another principle of behaviourism. It explains how behaviours are learned from and reinforced in response to consequences.

There are 3 types of consequences for behaviour:

- Positive reinforcement: Behaving in a way that gets rewarded/praised/you get something good in response for.

- E.g.: Doing your homework because it gets praised by the teacher

- Negative reinforcement: Behaving in a way to avoid negative/unpleasant/bad consequences.

- E.g.: Doing your homework to avoid getting told off by the teacher

- Punishment: Negative/unpleasant/bad consequences for behaviour.

- E.g.: Getting told off by the teacher for not doing your homework

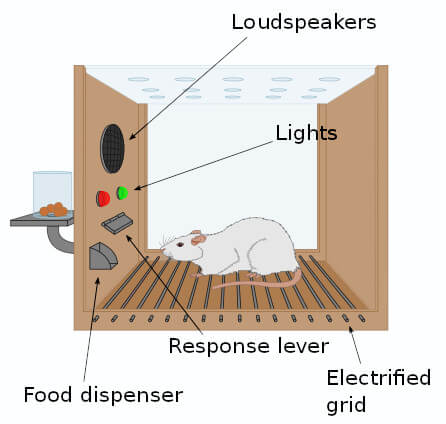

An example of operant conditioning is found in the research of Skinner (1948) and Skinner (1953). Skinner’s experiments involved putting animals (rats and pigeons) in cages like the one below:

In one variation of the experiment, pressing the response lever caused food to come out of the food dispenser. The rat quickly learned this consequence and so would repeat the behaviour to get more food. This is an example of positive reinforcement.

Another variation of the experiment demonstrated learning through negative reinforcement. In this setup, an electrified grid would cause pain to the rat but pressing the response lever turned the electrified grid off. Similar to the other experiment, the rats quickly learned to go straight to the response lever when put in the box.

These experiments demonstrate how learning through positive and negative reinforcement increases the chances of a behaviour being repeated.

AO3 evaluation points: Behaviourism

Strengths of behaviourism:

- Scientific: Behaviourism focuses on what is observable, measurable, and repeatable, which lends credibility to the study of psychology as a science.

- Practical applications: Behaviourism has been successfully applied in several psychological contexts to produce desirable behavioural results. One example of this is the behaviourist treatment of phobias, including flooding and systematic desensitisation. However, there are also more ethically dubious applications of behaviourism, such as use of operant conditioning to make social media algorithms, gambling machines, and similar such activities more addictive.

Weaknesses of behaviourism:

- Ignores the internal mind: By focusing only on environmental inputs (stimulus) and behavioural outputs (responses), behaviourism neglects the mental events in the middle such as thoughts, reflections, and emotions. This makes it difficult for behaviourism to explain behaviours such as memory, which happen internally and so cannot be observed. These internal aspects of the mind may be better explained by other psychological approaches such as the cognitive approach or social learning theory.

- Validity of animal studies: A basic assumption of behaviourism is the use of animal studies to explain human behaviour. But humans are very different to animals such as pigeons and rats – both physically and cognitively. As such, the conclusions drawn from studies on animals (e.g. Pavlov and Skinner) may not transfer to human psychology.

- Ethical concerns: There are several ethical questions that can be raised against behaviourism. For example, it may be argued that many animal experiments (e.g. Skinner’s) caused distress for the animals involved. In humans, it may be argued that certain applications of behaviourism (e.g. the social media and gambling machine examples above) are ethically wrong.

Social Learning Approach

Like behaviourism, the social learning approach to psychology also explains behaviour as a result of learning from experience, but adds the extra element of learning by observing others’ behaviour.

Basic assumptions

- Like behaviourism, social learning theory says behaviour is learned from experience. But whereas behaviourism focuses on classical and operant conditioning, social learning theory adds a social dimension: We learn not only from consequences of our own behaviour, but by observing and imitating other peoples’ behaviour.

- People imitate the behaviours of role models who they identify with. Behaviours may be reinforced vicariously, i.e. by seeing someone else be rewarded for that behaviour.

- Social learning theory is not entirely behaviourist: It allows for the inclusion of cognitive elements (e.g. mediating processes) in explaining behaviour.

Albert Bandura: Bobo the doll experiment

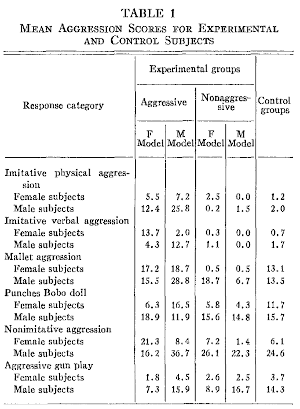

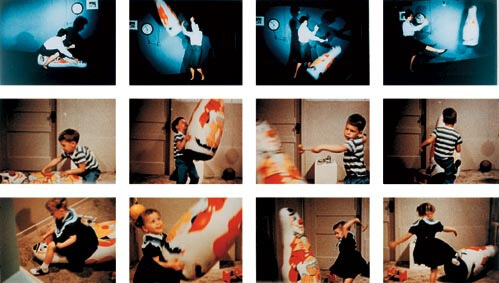

Bandura and Huston (1961) observed that children imitate the behaviours of role models they identify with. The aim of another study, Bandura et al (1961), was to see if this behavioural imitation continued even when the role model was no longer present.

The procedure of the study was as follows:

- Subjects were 36 boys and 36 girls aged between 3 and 6 years old

- They were each put into a room with an inflatable doll (Bobo) and observed an adult role model interact with the doll for 10 minutes

- The subjects were separated into groups as follows:

- Aggressive: Role model hits the doll with a hammer and shouts abuse at it

- Non-aggressive: Role model does not hit the doll or shout at it

- Control: No role model

- Half of the subjects had a role model of the same gender, while the other half had a role model of the opposite gender

- After observing the role model for 10 minutes, the participants were taken to a room with toys but told they couldn’t play with them (the aim of this was to increase aggression)

- After 2 minutes, the participants were taken to a room with lots of different toys (including a Bobo doll) and left to play with them for 20 minutes

The researchers observed the children playing during that 20 minutes and rated how closely they imitated the behaviour of the role model they had seen previously. The results were as follows:

- Children who had observed an aggressive role model previously acted more aggressively than children who had observed a non-aggressive role model

- Boys acted more aggressively than girls in general

- The child was more likely to imitate the behaviour of the role model if the role model was the same gender as them

These results illustrate many key concepts of social learning theory:

People imitate (copy) the behaviours of role models they identify with (i.e. people they are like or want to be like). For example, the fact that children were more likely to imitate/model the behaviour of the role model if they were of the same gender could be because they were more likely to identify with the role model.

Another key concept is vicarious reinforcement, which is where a person is more likely to imitate a behaviour if they observe the model being rewarded for it. Vicarious reinforcement is demonstrated in Bandura and Walters (1963), which was another variation of the Bobo the doll where the model was either praised or punished for acting aggressively towards the doll. Children who saw the model praised for their aggression toward the doll were more likely to imitate this aggressive behaviour.

Mediating processes

As mentioned above, social learning theory is not entirely behaviourist. We don’t just automatically imitate every behaviour we observe. Instead, there are various cognitive processes in between that determine whether someone imitates a behaviour or not.

These mediating processes are described in Bandura (1977) as follows:

| Attention | The behaviour has to be important/significant so as to grab our attention. |

| Retention | The observed behaviour has to be remembered/retained. If you don’t remember a behaviour then you can’t imitate it. |

| Reproduction | Our abilities may influence our decision to physically reproduce the behaviour. For example, an elderly lady might desire to reproduce breakdancing behaviour, but won’t attempt it because of a lack of physical ability. |

| Motivation | If we think through and conclude that a potential behaviour will be positively rewarded (e.g. because of vicarious reinforcement), this motivates us to imitate the behaviour. |

AO3 evaluation points: Social learning approach

Strengths of the social learning approach:

- Offers a more complete account than behaviourism: Whereas behaviourism is limited to stimulus and response only, the social learning approach allows for cognitive processes in explaining behaviour. For example, Bandura’s mediating processes allow that someone could internally reflect on what they’ve observed and make a judgement on how they will behave. This can explain why people often act differently in response to similar stimuli.

- Explains cultural differences: If children learn behaviours by modelling those around them (as social learning theory claims) then this explains different behaviours between cultures because the children imitate the behaviours of the culture. The biological approach, in contrast, may have difficulty explaining these variations because the biology is essentially the same between cultures but the behaviour is different.

Weaknesses of the social learning approach:

- Biological approach: Although the Bobo the doll experiments support social learning theory, they also support a biological approach. Bandura and colleagues consistently found that boys showed more aggression towards the dolls than girls independently of other conditions. This suggests that biological factors (e.g. testosterone levels) also play an important role in explaining behaviour and that the social learning approach is not, by itself, sufficient.

- Questions of ecological/external validity: The Bobo the doll experiments were conducted in an unfamiliar (laboratory) setting. Because of this new situation, the children might simply have been behaving in the way they thought they were expected to in this situation (copying the model). Further, the children would have known the doll was just a doll and so it is unclear whether the children would model aggressive behaviour towards, for example, other children in a real-life scenario.

Cognitive approach

The cognitive approach to psychology explains behaviour as a result of cognitive processes such as thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions.

Basic assumptions

- Inner mental processes (e.g. thoughts and perceptions) can and should be studied in a scientific way.

- Although a person’s inner mental processes can’t be observed, they can be inferred from their external behaviour. So, the cognitive approach is kind of in between behaviourism and introspection: behaviourism is wrong to focus only on behaviour, but introspection’s focus on private mental states alone is too subjective to count as proper science.

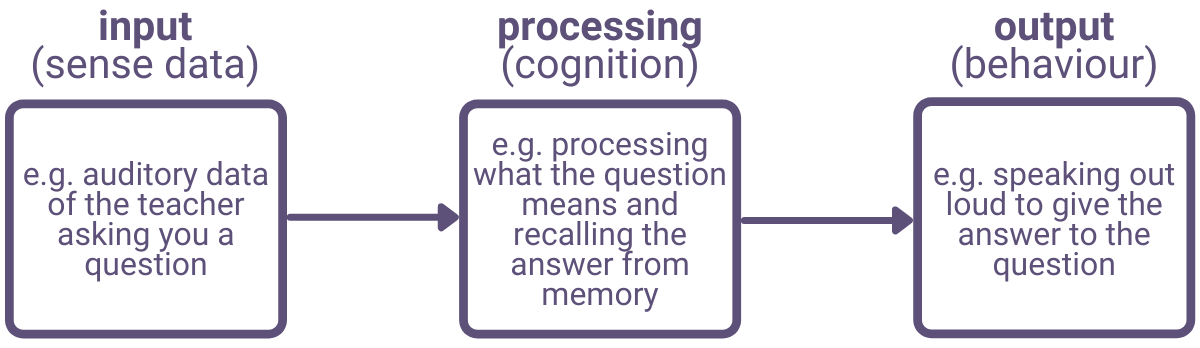

- Mental processes can be modelled like a computer program: inputs (e.g. sense data) get processed in the mind (like a computer program) to produce outputs (i.e. behaviour). Whereas behaviourism focuses only on the inputs and outputs, the cognitive approach acknowledges on the thing in the middle: the mental process.

Schema

Schema are a key part of the cognitive approach. They are cognitive frameworks, mental models, patterns of thought and behaviour. They are mental short-cuts, ways of organising information and understanding the world.

Examples of schema include:

- Self-schema, e.g. physical “I’m tall” and personality e.g. “I’m kind”

- Stereotypes/generalisations, e.g. “dark alleys at night = dangerous”, “revision is boring”

- Social roles, e.g. “customers join the queue before paying”, “police catch criminals”

- Motor schema, e.g. how to walk, babies are born with schema to feed

Basically, schema covers a lot of things. Our schemas inform our perception of the world – they are the cognitive lens through which we make sense of reality.

Schema are formed from experience. We form schema blueprints and use them to interpret the past, categorise information in the present, and form expectations/predictions for the future. Because people have different experiences, they have different schema.

Schema change over time. For example, a young child might form the simple schema that dog = 4 legged furry animal. But this schema would include cats, too. So, over time, the child refines its schemas to become more detailed.

However, once a schema is formed, it can be difficult to change: People tend to be biased towards information that fits pre-existing schema, and often ignore or re-interpret contradictory information in order to fit their existing schema.

Models

Computer models

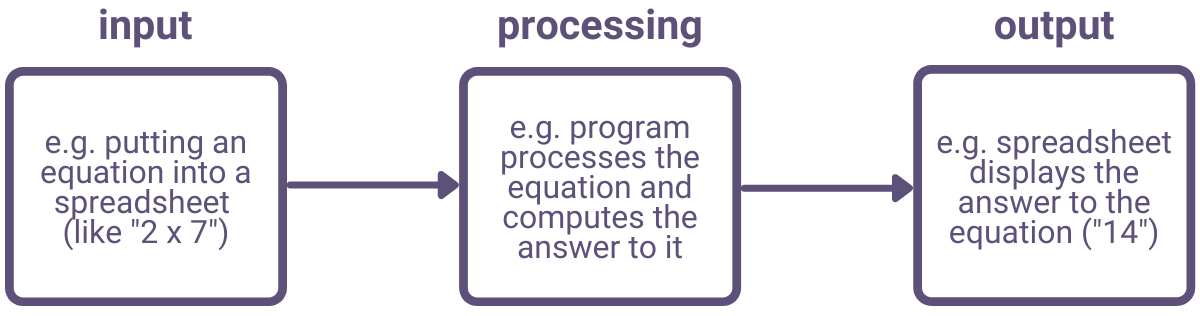

Advocates of the cognitive approach often think of mental processes as analogous to computer processes. With a computer, data goes in, it gets processed, then you get an output.

Obviously this is a very simple example, but all computer programs work in this way. When you’re playing a game, for example, controller inputs are processed, which changes the output displayed on screen. When you input a URL in your browser, it gets processed (through multiple computers) until the browser displays the output of the website you entered.

The mind can be said to work in a similar way: Input from your senses is processed by the mind to produce an output. For example:

So, the cognitive approach explains behaviour as a series of processing steps analogous to the processing steps of a computer. These processing steps can be broken down into theoretical models, which can be tested against observation to see if they are accurate.

Theoretical models

The cognitive approach uses theoretical models to explain the cognitions (mental processes) behind behaviour.

An example of such a theoretical model is the multi-store model of memory from elsewhere in the course: It explains how information flows through various components for processing. For example, paying attention to sensory information causes it to be transferred (processed) to short-term memory.

Emergence of cognitive neuroscience

Cognitive neuroscience is the study of the relationship between brain activity and mental processes. It looks at the biological workings underlying cognition and so can be thought of as a mixture between the cognitive and biological approaches.

As technology has advanced (most notably brain-scanning techniques such as fMRI and PET), scientists have been able to identify correlations between certain types of brain activity and certain types of mental processes. For example, Braver et al (1997) observed that greater working memory load (a cognitive concept) is correlated with greater prefrontal cortex activity (a biological concept). This suggests the underlying biological basis for working memory is situated in that area of the brain. As cognitive neuroscience advances, more cognitive processes might be analysable in biological terms.

AO3 evaluation points: Cognitive approach

Strengths of the cognitive approach:

- Acknowledges mental processes: It is obvious that mental processes (thoughts, reflections, emotions, etc.) are important in determining behaviour. The cognitive approach recognises the importance of these mental processes and studies them (unlike e.g. behaviourism).

- Scientific: Although mental processes cannot directly be observed, the cognitive approach uses rigorous experimental methods based on observable data to infer details of them.

- Practical applications: Therapies based on the cognitive approach (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy) have been shown to produce positive results. For example, many studies have shown CBT to improve symptoms of depression.

Weaknesses of the cognitive approach:

- Overly reductive: The cognitive approach’s analogy between the mind and a computer has its limitations. Although there are similarities between the two types of processing, there are important differences. For example, human emotions (which computers lack) have a significant effect on processing, which is not accounted for in a purely information-processing model. An example of this in action is the effect anxiety has on eyewitness testimony.

- Questions of ecological/external validity: Theories based on the cognitive approach (e.g. the working memory model) are often based on laboratory studies, but these results might not translate to real-life. For example, Baddeley’s (1996) test of the capacity of the central executive is an unusual task that one wouldn’t normally perform in real-life.

Biological approach

The biological approach to psychology explains behaviour as a result of biological factors such as genetics, biological structures, and neurochemistry.

Basic assumptions

- A full understanding of human behaviour will look at the underlying biological processes that cause it. Psychological processes are, at first, biological processes.

- These biological processes include:

- Genetics: i.e. biological traits inherited from parents.

- Biological structures: the physical systems that make up the mind and body (in particular the nervous system).

- Neurochemistry: i.e. chemicals such as hormones and neurotransmitters.

- The mind is the brain (unlike e.g. the cognitive approach which treats the mind as something separate to the brain).

Genetics

Just as physical characteristics – such as eye colour and hair colour – are determined by genetics inherited from parents, so too are certain behavioural tendencies.

An example of this is the genetic explanation of OCD from elsewhere in the course. But other psychological traits – e.g. intelligence, or aggression – also have a genetic component that can be passed on from parents to children.

Genotype and phenotype

Genetic effects can be divided into genotype and phenotype:

- Genotype: Your actual genes. These are decided at conception and consist of around 100,000 genes that cannot be changed.

- E.g. eye colour or hair colour. Obviously you can dye your hair, but your hair still grows back the same colour that is determined by your genotype. Similarly, you might be born with the SLC1A1 gene, which is linked to OCD.

- Phenotype: How your genes present in response to the environment. Even though your genotype itself can’t change, the way it’s expressed can vary.

- E.g. height has a strong genetic component, but a person with tall genes could end up short if they grow up in a malnourished environment. Similarly, a person with a genetic tendency towards OCD could use psychotherapy to overcome these genes and not exhibit OCD behaviours.

Twin studies

Twin studies can confirm the genetic influence of psychological traits.

The concordance rate is the rate at which twins share the same trait. If the concordance rate for a psychological disorder is higher among identical twins (monozygotic twins) than non-identical twins (dizygotic twins), this suggests a genetic component to the disorder.

The concordance rate is the rate at which twins share the same trait. If the concordance rate for a psychological disorder is higher among identical twins (monozygotic twins) than non-identical twins (dizygotic twins), this suggests a genetic component to the disorder.

The reason for this is that the identical twins have 100% identical genetics whereas non-identical twins only share 50% of their genes. So, if a disorder is entirely determined by genetics, then identical twins would both develop the disorder because they share identical genes. However, because non-identical twins only share 50% of their genes, there is a chance that only one of them will inherit the genetics for the disorder but not the other.

| Disorder | Identical twins concordance rate | Non-identical twins concordance rate |

| OCD | 68% | 31% |

| Bipolar depression | 40-70% | 5-10% |

| Schizophrenia | 48% | 17% |

In reality, most psychological disorders are a combination of genetic and environmental factors. However, the examples above illustrate how there is a strong genetic component to many psychological disorders. If one identical twin has OCD, for example, there is a 68% chance the other twin will too.

Evolution

If psychological behaviours and psychological disorders have a genetic component (as the biological approach believes), then it follows that these psychological traits would be subject to evolution in the same way that physical traits are.

For example, intelligence: If there was a gene that made a human better at hunting food, then the human with that gene would be less likely to starve to death and so more likely to pass on their genes to the next generation.

Another example of evolved psychological traits could be Bowlby’s monotropic theory of attachment. Bowlby argued that babies evolved to develop an attachment to one person – usually its mother. This behaviour makes the baby more likely to survive and pass on its genes because a baby that does not develop an attachment will be left to fend for itself in a dangerous environment and probably die before it gets the chance to procreate.

Another example of evolved psychological traits could be Bowlby’s monotropic theory of attachment. Bowlby argued that babies evolved to develop an attachment to one person – usually its mother. This behaviour makes the baby more likely to survive and pass on its genes because a baby that does not develop an attachment will be left to fend for itself in a dangerous environment and probably die before it gets the chance to procreate.

Biological structures

In addition to the biological dimension of genetics, the biological approach also looks at the influence of biological structures on psychological traits and behaviour. These biological structures are covered in more detail in the biopsychology module and include:

- The central nervous system (i.e. the brain and spinal cord)

- Neurons

- The endocrine system

Neurochemistry

Another aspect of the biological approach is neurochemistry. Again, this is covered in more detail in the biopsychology module and primarily concerns:

- Hormones (e.g. testosterone, estrogen, cortisol)

- Neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin, dopamine, glutamate)

AO3 evaluation points: Biological approach

Strengths of the biological approach:

- Supporting evidence: The fact that concordance rates for behaviours and psychological disorders are often higher among monozygotic twins than dizygotic twins (e.g. Gottesman (1991) for schizophrenia, Holland et al (1988) for anorexia, and Verhulst et al (2015) for alcoholism) supports biological (genetic) explanations of behaviour.

- Scientific: The biological approach focuses on observable and measurable phenomena such as hormone levels, brain structures, and genes. These biological phenomena are often measured using sophisticated technology (e.g. fMRI scanners) and tested using rigorous scientific methods (e.g. randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials of drugs).

- Practical applications: Biological approaches have proven highly successful in treating mental disorders. For example, we saw in the psychopathology topic how drugs such as SSRIs are highly effective for treating OCD. Similarly, drug therapy is successfully used to treat depression, anxiety, and other psychological conditions. Further, tools to better understand and measure biological structures (e.g. fMRI scanning) yield new explanations and ways of treating psychological disorders.

Weaknesses of the biological approach:

- Conflicting evidence: Despite high concordance rates for certain behaviours and psychological disorders among identical twins (see supporting evidence above), these concordance rates are much lower than 100%. This suggests there are other factors besides genetics needed to fully explain behaviour.

- Overly reductive: The biological approach can be said to be overly reductive in that it ignores other factors, such as environment. For example, a person with the same genes is likely to behave differently if raised by a different family or in a different culture. This shows that genetics can only go so far in explaining human behaviour.

- Deterministic: The biological approach explains behaviour as a result of biological factors outside our control, such as genetics and biological structures. This leaves no room for free will, which makes it difficult to hold people responsible for their actions as those actions are just a consequence of biology rather than being freely chosen by the individual. This raises both moral and legal issues: How is it fair to send someone to prison, for example, for something they didn’t choose to do?

Psychodynamic approach

Note: This topic is A level only, you don’t need to learn about the psychodynamic approach if you are taking the AS exam only.

The psychodynamic approach to psychology explains behaviour as a result of unconscious processes.

Basic assumptions

- The mind consists of multiple parts: The conscious mind, the pre-conscious mind, and the unconscious mind. The unconscious mind includes biological instincts that cannot consciously be accessed but that have a significant influence on behaviour.

- Behaviour is explained as a result of conflicts between these different aspects of the mind.

- Early childhood experiences shape us as adults. Failure to resolve conflicts (e.g. not properly progressing through the five psychosexual stages) in childhood can lead to psychological problems as an adult.

Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytic theory

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory is the most influential example of a psychodynamic approach to psychology. It emphasises the role of the unconscious mind in determining behaviour.

The role of the unconscious

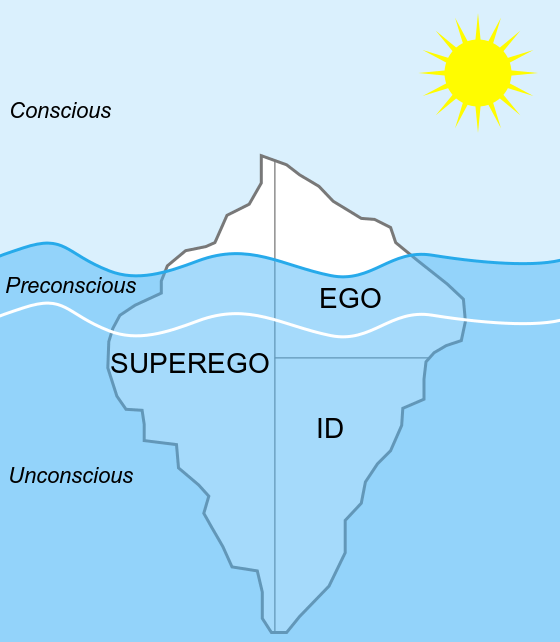

A bit like an iceberg, the vast majority of the mind is below the surface of what we are consciously aware of. According to Freud, there are three ‘levels’ of consciousness, arranged vertically in a hierarchy:

- Conscious: What we are directly aware of.

- Pre-conscious: Memories, thoughts, and beliefs we are not directly aware of but that can be accessed by making an effort to do so.

- Unconscious: Everything else (and there is a lot) including biological drives, instincts, desires, repressed memories, and fears. These cannot easily be accessed (at least not without psychoanalytic therapy).

A lot of significant psychological activity happens below the level of what is consciously available. However, these unconscious thoughts often bubble to the surface in things like dreams and ‘Freudian’ slips of the tongue (e.g. accidentally calling your girlfriend ‘Mum’). Psychoanalysts use psychoanalysis to identify and interpret these unconscious thoughts and their meanings, which then serve as a basis for treating psychological disorders.

Structure of personality

Freud proposed a tripartite structure of personality:

- Id: The primitive, biological, part of personality. It is present from birth and operates on the pleasure principle, demanding gratification of its needs.

- Ego: The part of personality that mediates between the id and the superego. It develops around 1-3 years old and operates on the reality principle.

- Superego: The moral ‘higher values’ part of personality. It develops around 3-5 years old and operates on the morality principle, punishing the ego through guilt.

According to this theory, behaviour is determined by the interaction of these three parts. The ego sits in the middle and tries to balance the competing demands of the id (i.e. base biological drives) and superego (i.e. moral beliefs about right and wrong). Improper balance between the id and superego creates anxiety and is the cause of mental disorders. One way in which the mind resolves these conflicts is via defence mechanisms.

Defence mechanisms

Defence mechanisms are a way in which the ego manages conflict between the id and superego. They include:

- Repression: Hiding an unpleasant or undesirable thought (e.g. sexual or aggressive urges) or memory (e.g. childhood abuse) from the conscious mind.

- Denial: Rejecting and refusing to accept reality (e.g. failing to acknowledge that your girlfriend doesn’t love you any more after you break up).

- Displacement: Redirecting emotions from the actual target to a substitute (e.g. kicking your cat because you’re angry about an episode that happened at work that day).

Psychosexual stages

According to Freud, normal development in childhood involves passing through five psychosexual stages. At each stage, a conflict must be resolved before moving on to the next stage. If a conflict is not resolved, the child becomes stuck at that stage, which affects their behaviour as an adult.

The five psychosexual stages are as follows:

| Stage | Age | Pleasure focus |

Description |

| Oral | 0-1 years | Mouth | Feeding (mother’s breast) is the object of pleasure |

| Anal | 1-3 years | Anus | Pleasure from withholding and expelling faeces |

| Phallic | 3-5 years | Genitals | Masturbation: Desire focuses on penis or clitoris |

| Latency | 5 years-puberty | Repressed | Sexual desires are repressed |

| Genital | Puberty | Genitals | Sexual desires are conscious and are directed towards having sex |

An example of getting stuck: If you’ve ever heard someone describe a person as ‘anal’ and thought it was a weird word to describe someone who’s obsessive about detail, it comes from Freud. According to the theory, if toilet training is too strict, it can manifest as a (anal retentive) personality that is obsessive about details, tidiness, routine, etc. If toilet training is too relaxed, it manifests the opposite personality (anal expulsive), i.e. messy and disorganised.

Another famous example of psychosexual conflict is the Oedipus complex, which occurs at the phallic stage. According to Freud, boys develop a sexual attraction towards their mother during this stage and a hatred of their father.

AO3 evaluation points: Psychodynamic approach

Strengths of the psychodynamic approach:

- Explanatory power: Although much of Freud’s work is scientifically controversial (see below), it has some explanatory power. For example, Freud’s theories were among the first to explain how experiences in early childhood influence adult personality. This idea is now common to many other psychological theories, such as Bowlby’s continuity hypothesis and the double bind explanation of schizophrenia.

- Practical applications: Freud’s theories yielded a treatment form known as psychoanalysis, which involves accessing and interpreting the unconscious mind (e.g. via dream analysis, free association). There is some evidence that psychoanalysis can successfully treat mild neuroses (though not serious mental disorders like schizophrenia) and later therapies developed from Freudian psychoanalysis (talking therapies) are still used today.

Weaknesses of the psychodynamic approach:

- Unscientific/pseudoscientific: Science is about what can be measured, observed, and repeated. By this standard, Freud’s theories are much less scientific than e.g. the behaviourist or biological approaches. For example, unconscious concepts (e.g. the id) are not even observable by the individual themself let alone measurable in a lab! Further, Freud’s theories were primarily based on individual case studies rather than measurable and quantified data. As such, Freud’s interpretation of the results is highly subjective. The relatively small number of case studies may also mean the theories derived from them may not apply to human psychology in general.

- Ignores other factors: The psychodynamic approach explains mental disorders as a result of conflict between different aspects of the mind but this ignores other explanations (e.g. biological). For example, there are physical differences in both the neurochemistry and biological structures of people with OCD and without. Treating these physical causes is likely to be more effective for many psychological disorders.

Humanistic psychology

Note: This topic is A level only, you don’t need to learn about humanistic psychology if you are taking the AS exam only.

Humanistic psychology rejects scientific and objective explanations of behaviour, instead arguing that human experience is subjective and that humans have free will to choose their behaviour.

Basic assumptions

- The humanistic approach emphasises the free will of the individual.

- Each individual is unique and so psychology should focus on the experience of each individual (subjective or idiographic approach) rather than trying to identify general rules of human behaviour (objective or nomothetic approach).

- Rather than focusing on one aspect of a person (e.g. biological factors or childhood experiences), the humanistic approach believes each person should be viewed holistically.

Free will

Free will is the philosophical view that humans are able to make choices for themselves – without being controlled by the influences of biology or environment. It is a key assumption of the humanistic approach. Humanistic psychologists see humans as free to change and make decisions that lead to self-actualisation.

Self-actualisation

The humanistic approach believes all humans have a desire to achieve self-actualisation. Self-actualisation means fulfilling your potential – developing your abilities and skills, successfully deploying them, and enjoying doing so. Because each human is different, self-actualisation will differ from person to person.

Humanistic psychologists Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers characterised self-actualisation in different ways:

- Maslow: Meeting all levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the top of which includes creativity, problem solving, and full achievement of potential.

- Rogers: Having unconditional positive regard and achieving congruence between self-concept (how you see yourself) and ideal self (the version of yourself you want to be). Rogers’ treatment approach is counselling psychology, which aims to help individuals self-actualise.

Abraham Maslow: Hierarchy of needs

Maslow’s (1943) view of self-actualisation involves satisfying 5 levels in a hierarchy of needs.

At the bottom of the hierarchy are the most essential physiological needs – without things like food, water, and air to breathe, you die. The next most essential needs are safety (e.g. having a home), followed by social (e.g. having friends and romantic relationships), and then esteem needs (e.g. a job you are good at).

At the bottom of the hierarchy are the most essential physiological needs – without things like food, water, and air to breathe, you die. The next most essential needs are safety (e.g. having a home), followed by social (e.g. having friends and romantic relationships), and then esteem needs (e.g. a job you are good at).

These lower levels of the hierarchy are deficiency needs. A person without these basic needs is lacking and must address them before they can reach the final stage of the hierarchy: self-actualisation.

Self-actualisation is a growth need. It involves fulfilling your full creative, moral, and intellectual potential. A self-actualising person is one who is constantly striving towards and achieving a worthy goal. Maslow gave various examples of self-actualised people, including Albert Einstein, but believed only around 1% of people truly achieve self-actualisation.

Carl Rogers

Rogers’ view of self-actualisation builds on Maslow’s hierarchy. According to Rogers, self-actualisation also involves unconditional positive regard and congruence between how a person sees themself and their ideal version of themself.

Conditions of worth

Rogers argues that self-actualisation requires positive self-regard (i.e. a positive opinion of yourself).

But if a person’s parents impose conditions of worth on them, them are less likely to have positive self-regard. For example, if a parent only praises and loves their child when they do well in school, or win competitions, then their love is conditional. This can cause feelings of low self-esteem and worthlessness that prevent self-actualisation.

In contrast, children whose parents have unconditional positive regard for them are more easily able to achieve self-actualisation.

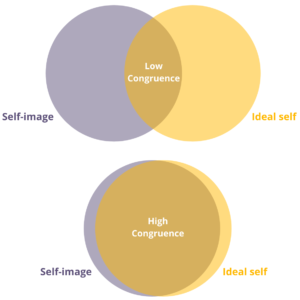

Congruence

Congruence refers to how closely two things overlap.

According to Rogers, self-actualisation requires that a person’s self-image (how they view themself) is highly congruent with, i.e. similar to, their ideal self (how they would like to be).

According to Rogers, self-actualisation requires that a person’s self-image (how they view themself) is highly congruent with, i.e. similar to, their ideal self (how they would like to be).

If the gap between a person’s self-image and their ideal self is too high (low congruence), it will be harder to achieve self-actualisation.

Counselling psychology

The humanistic approach has been influential on counselling therapy, which originated with Rogers.

According to Rogers, the core qualities of a good counselling therapist are:

- Genuine: The therapist doesn’t hide behind a professional facade that is incongruent with their real personality.

- Unconditional positive regard: The therapist accepts and values the client for who they are without disapproval or judgement.

- Empathy: The therapist actively tries to understand and appreciate the client’s perspective.

The aim of Rogers’ counselling psychology (also called person-centred therapy) is to increase congruence between the client’s self-image and ideal self and increasing their feelings of self-worth. Ultimately, this helps the client to self-actualise and fulfil their potential.

AO3 evaluation points: Humanistic psychology

Strengths of humanistic psychology:

- Practical applications: The humanistic approach has yielded therapies that have helped people. For example, counselling psychology is commonly used within social work and has helped many people improve their lives. This is supported by a review by Sexton and Whiston (1994), who found that person-centred therapy was effective for some people. Beyond psychology, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has been influential within the business world to explain and help improve motivation within the workplace.

- Holistic: Whereas other psychological approaches are reductive (e.g. behaviourism reduces the mind to stimulus and response, the biological approach reduces the mind to biological structures and neurochemistry) the humanistic approach considers all aspects of a person’s life. This holistic approach may yield more valid insights and treatment as it is based on real-life experience and context rather than artificial and unrealistic laboratory experiments.

Weaknesses of humanistic psychology:

- Unscientific: Science is about what can be measured, observed, and repeated. But the subjective approach of humanistic psychology means it does not produce this kind of quantifiable or replicable data. As such, it is hard to objectively test the claims of the humanistic approach against reality and say whether they are true or not. Further, science involves developing hypotheses and general theories that explain behaviour, but humanistic psychology is idiographic and so rejects attempts to generalise behaviour in this way.

- Cultural differences: Self-actualisation within the humanistic approach focuses entirely on the individual achieving their own potential. However, more collectivist cultures emphasise the common good and may prefer to focus on achieving community or societal potential rather than individual self-actualisation.