Overview – Gender

Gender refers to the psychological traits of masculinity and femininity. A person’s gender is a different thing to their biological sex, although the two things often overlap. This topic looks at:

- How sex and gender relate to each other (including sex-role stereotypes and androgyny)

- Biological influences on sex and gender (including the role of chromosomes and hormones)

- Cognitive explanations of gender development (in particular Kohlberg’s theory and gender schema theory)

- Psychodynamic explanations of gender development (in particular Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of gender)

- Social learning explanations of gender development (including the role of culture and the media)

- Atypical gender development (including biological and social explanations of gender dysphoria)

Sex and gender

There is a difference between sex and gender, but the two things often overlap:

- Sex: Whether a person is biologically male or female (i.e. what sex organs and chromosomes they have).

- Gender: Whether a person is psychologically masculine and/or feminine (i.e. how they act and what they identify as).

The different sexes have different sex-role stereotypes. If someone has a mix of masculine and feminine traits, they are androgynous.

Sex-role stereotypes

Sex-role stereotypes are social and cultural expectations of how males and females should behave. Some typical examples include:

- Women are more nurturing than men

- Men are more aggressive than women

- Men like football, women don’t

- Caring for children is women’s work, men do the DIY

- Pink is a girl’s colour, blue is a boy’s colour

Some sex-role stereotypes are valid. For example, the stereotype that men are more aggressive than women is likely to reflect a valid biological difference between the sexes. However, many stereotypes, such as women wearing skirts and men wearing trousers, have no basis in biology and are entirely created by culture.

Some sex-role stereotypes are valid. For example, the stereotype that men are more aggressive than women is likely to reflect a valid biological difference between the sexes. However, many stereotypes, such as women wearing skirts and men wearing trousers, have no basis in biology and are entirely created by culture.

AO3 evaluation points: Sex-role stereotypes

- Different stereotypes: There is unlikely to be a one-size-fits-all explanation of gender stereotypes, as there are many different forms of stereotype. For example, as described above, the stereotype that men are more aggressive than women is likely to have a biological explanation, whereas the stereotype that women wear skirts and men wear trousers is likely to have a cultural explanation.

- Interactionism: The various discussions below suggest biological, social, cognitive, and psychodynamic explanations of sex-role stereotypes and gender roles. One way to reconcile these competing explanations is to adopt an interactionist approach. Instead of relying on only one explanation, you might argue that some sex-role stereotypes have a biological basis that gets reinforced and amplified by social learning, for example.

- Negative effects: Sex-role stereotypes may have harmful effects on society. For example, women may not go into fields such as science or technology – even if they are equally talented as men – because sex-role stereotypes might tell them these are ‘male’ industries. Similarly, men may avoid going into fields such as nursing and childcare due to sex-role stereotypes.

Androgyny

Androgyny is when someone has a mix of both feminine and masculine traits. It is commonly used to refer to someone’s appearance (e.g. a female with short hair or a man wearing makeup), but in this context we are talking about psychological androgyny.

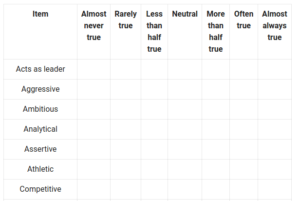

Androgyny can be measured using the Bem sex-role inventory.

Bem sex-role inventory

Bem (1974) created the Bem sex-role inventory to measure a person’s masculine and feminine traits. It is a self-report method that asks participants to rate themselves on a scale of 1-7 for 60 items (20 masculine, 20 feminine, 20 neutral). You can see the full list here.

created the Bem sex-role inventory to measure a person’s masculine and feminine traits. It is a self-report method that asks participants to rate themselves on a scale of 1-7 for 60 items (20 masculine, 20 feminine, 20 neutral). You can see the full list here.

Bem (1977) describes four broad personality types that are captured by the Bem sex-role inventory:

- Masculine: High masculinity and low femininity

- Feminine: High femininity and low masculinity

- Androgynous: High masculinity and high femininity

- Undifferentiated: Low masculinity and low femininity

Bem argues that androgyny – scoring highly for both masculinity and femininity – is psychologically healthy and advantageous. One reason androgyny may be advantageous is that having a mix of masculine and feminine traits enables a person to adapt and excel in more situations, whereas a person who scores highly one way but not the other is likely to have a more limited skillset.

AO3 evaluation points: Bem sex-role inventory and androgyny

Strengths of the Bem sex-role inventory:

- Reliability: Bem (1974) re-administered the Bem sex-role inventory to a sample of participants 4 weeks after they originally completed the test. She found the participants’ answers were consistent both times, suggesting the Bem sex-role inventory has good test-retest reliability.

- Predictive power: Some studies (e.g. Flaherty and Dusek (1980) and Lubinski et al (1981)) support Bem’s prediction that androgyny is psychologically advantageous.

Weaknesses of the Bem sex-role inventory:

- Questions of cultural and temporal validity: The items in the Bem sex-role inventory were decided based on surveys of what American students in the 1970’s considered to be desirable traits for each gender. However, other cultures might have different ideas about which traits are masculine and feminine and so the Bem sex-role inventory might not be valid when applied outside of America. Similarly, American values may have changed since the 1970’s and so the Bem sex-role inventory may also lack temporal validity when measuring gender in American participants today.

- Subjective: Self-report methods such as the Bem sex-role inventory are subjective because they require participants to assess their own personality (rather than e.g. an independent observer objectively assessing each participant). Each participant’s different subjective interpretations, biases, and ways of understanding the items on the checklist may reduce the validity of the Bem sex-role inventory.

- Overly simplistic: The Bem sex-role inventory focuses solely on personality traits and reduces gender to a single number. However, this may be an oversimplification. For example, Golombok and Fivush (1994) argue that gender identity also includes things like interests and abilities.

Biological influences on gender development

Chromosomes (genetics) determine a person’s biological sex, which influences their natural hormone levels. In addition to physical effects, these biological factors have psychological effects that influence gender development.

Chromosomes

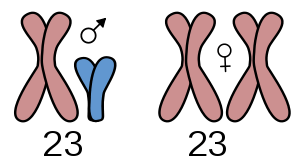

Each cell in the body (with a few exceptions) has chromosomes, which carry genetic information. Humans have 46 chromosomes, or 23 pairs. The 23rd chromosome pair determines a person’s biological sex.

Under a microscope, the 23rd chromosome pair looks different depending on whether someone is male or female:

Under a microscope, the 23rd chromosome pair looks different depending on whether someone is male or female:

- Females: XX

- Males: XY

Females have two pairs of X chromosomes, whereas males have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome. It is genes in the Y chromosome that are responsible for male development, such as the formation of testes and higher levels of the hormone testosterone.

Atypical sex chromosome patterns

Atypical sex chromosome patterns are when a person has a 23rd chromosome pair that is something other than the typical XX pattern for females or XY pattern for males. These atypical sex chromosome patterns cause differences in development compared those with typical sex chromosome patterns.

Klinefelter’s syndrome

Klinefelter’s syndrome (also known as 47,XXY) is when a male is born with XXY chromosomes rather than XY sex chromosomes. It affects roughly one in 750 males.

Physical characteristics of Klinefelter’s syndrome may include:

- Less body hair than average males

- Gynaecomastia (increased breast tissue)

- Poorly functioning testicles (sterility)

- Weaker muscles

- Taller height than average males

Psychological characteristics of Klinefelter’s syndrome may include:

- Low libido

- Below average reading ability and poor language skills

- Shyness and difficulties with social interaction

Turner’s syndrome

Turner’s syndrome (also known as 45,X) is when a female is born with only one X chromosome and either an absent or partial second X chromosome. It affects roughly one in 5,000 females.

Physical characteristics of Turner’s syndrome may include:

- No menstrual cycle (sterility)

- Undeveloped breasts

- Webbed neck, broad chest, narrow hips

- Shorter height than average females

Psychological characteristics of Turner’s syndrome may include:

- Above average reading abilities

- Below average mathematics abilities

- Social immaturity

Hormones

Hormones are chemicals produced in the body by glands (see the biopsychology page for more details).

All humans produce the same hormones – but males and females produce them in different amounts. For example, men produce much higher levels of testosterone, whereas women produce much more estrogen. In the womb, the different levels of these hormones affect brain development and cause the development of either male or female genitals. At puberty, hormone levels increase, causing the development of secondary sex characteristics (e.g. development of breasts in women, growth of facial hair in men). Hormones are associated with sex-role behavioural stereotypes and so are an important influence on gender development.

Testosterone

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone in males. On average, men have around 10 times as much testosterone as women. These higher testosterone levels have psychological effects that contribute to gender differences.

Testosterone is the primary sex hormone in males. On average, men have around 10 times as much testosterone as women. These higher testosterone levels have psychological effects that contribute to gender differences.

During development in the womb, genes in the Y chromosome cause testes, rather than ovaries, to form. At around 8 weeks, the testes start producing testosterone. This testosterone causes physical changes, such as the development of male sex organs, and also psychological ones because prenatal testosterone causes masculinisation of the brain. For example, men typically have greater spatial reasoning than women, with animal studies (e.g. Williams and Meck (1991)) and studies of females exposed to high levels of prenatal testosterone (e.g. Puts et al (2008)) suggesting testosterone plays a role in developing these areas of the brain.

After birth, testosterone is associated with stereotypical male behaviours, such as aggression and competitiveness. For example, Albert et al (1989) found injecting female rats with testosterone made them act more aggressively. In humans, Dabbs et al (1995) studied a prison population, finding prisoners with higher testosterone levels were more likely to have committed violent crimes.

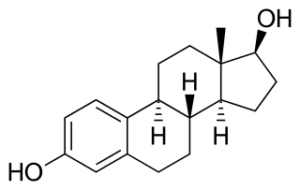

Estrogen

There are several  estrogen (also spelt oestrogen) hormones within the human body, the most common of which is estradiol. Estrogens are associated with female development, with women typically having 10 times as much estradiol as men. These higher estrogen levels contribute to gender differences.

estrogen (also spelt oestrogen) hormones within the human body, the most common of which is estradiol. Estrogens are associated with female development, with women typically having 10 times as much estradiol as men. These higher estrogen levels contribute to gender differences.

In the womb, having an X chromosome instead of Y means ovaries, rather than testes, form. This results in higher estrogen levels and lower testosterone levels. These higher estrogen levels have feminising effects on brain development. For example, some studies (e.g. Ardekani et al (2013)) have found women have more neural connections between the left and right hemispheres than men, resulting in more evenly distributed use of both brain hemispheres. Further, women generally have greater verbal fluency than men, with some studies (e.g. Schultheiss et al (2020)) suggesting this is a result of estrogen exposure.

Estrogen is associated with stereotypical female behaviours, such as compassion and sensitivity. After puberty, estrogen also regulates the menstrual cycle in women. In some women, hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle cause pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) – a condition with psychological symptoms that include stress, anxiety, and irritability. However, some researchers (e.g. Rodin (1992) and Offman and Kleinplatz (2004)) criticise the characterisation of PMS as a medical disorder.

Oxytocin

Oxytocin is sometimes called the ‘love hormone’ because it is associated with bonding, nurturing, trust, and sociability. Oxytocin levels are typically higher in women than men and the effects of oxytocin are amplified by estrogen, so oxytocin contributes to gender differences.

Oxytocin plays an important role in childbirth by causing contractions. After the baby is born, oxytocin stimulates lactation to enable breastfeeding. Oxytocin also helps form an emotional bond between mother and baby.

Oxytocin plays an important role in childbirth by causing contractions. After the baby is born, oxytocin stimulates lactation to enable breastfeeding. Oxytocin also helps form an emotional bond between mother and baby.

Oxytocin may partly explain sex-role stereotypes to do with childcare, sociability, and relationships. For example, oxytocin levels increase during sex by roughly 5 times – for both men and women – but fall immediately in males after orgasm. This may explain why males are less interested in intimacy after sex. Another example is gender differences in behavioural responses to stress. Typically characterised as ‘fight or flight‘, Taylor et al (2000) found the female response to stress is better characterised as ‘tend and befriend’. The researchers suggest these behavioural differences in response to stress are caused by differences in oxytocin activity between men and women. In another study, Zak et al (2007) randomly assigned participants to receive either an oxytocin injection or placebo before getting the participants to take part in a task that involved splitting money with another person. The participants injected with oxytocin were 80% more generous than controls.

AO3 evaluation points: Biological influences on gender (chromosomes and hormones)

Strengths of biological explanations:

- Evidence supporting biological explanations: See studies above for examples of how hormones influence gender development. Another useful example is Van Goozen et al (1995), who demonstrated that administering cross-sex hormones to transgender people results in gender-stereotypical behavioural changes. For example, FtMs given testosterone act more aggressively and MtFs given estrogen act less aggressively. Further, atypical sex chromosome patterns – such as Klinefelter’s Syndrome and Turner’s Syndrome – demonstrate how chromosomes also have important effects on gender development. Finally, several studies (e.g. Alexander et al (2009), Caldera et al (1989), and Hassett et al (2008)) have found babies display gender-typical behaviour as early as 3 months old, suggesting some gender-typical behaviours are biologically programmed from birth.

Weaknesses of biological explanations:

- Conflicting evidence: Some studies question the effects of hormones on gender-typical behaviour. For example, Tricker et al (1996) randomly assigned 43 men to receive either 600mg of testosterone per week or placebo but found no differences in aggression between the two groups.

- Other factors: Although there is strong evidence for a biological component to gender, other factors – such as cognitive factors and social learning – likely play a role as well.

- Socially sensitive: A potential negative consequence of biological explanations of gender development is that it could reinforce harmful stereotypes. For example, if males have a slight advantage in spatial reasoning on average, it might cause society to discriminate against women entering fields that require spatial reasoning (e.g. engineering) even if the woman is equally or more able than the average man.

- Methodological concerns: A lot of evidence for the role of hormones in gender development comes from animal studies and so the results might not apply to humans.

Cognitive explanations of gender development

Cognitive explanations of gender development see gender resulting from active changes in thought over time as a child grows up (as opposed to social learning theory, which says gender is just passively observed and imitated). They describe the ways of thinking that contribute to gender development.

The cognitive explanations of gender included in the syllabus are Kohlberg’s theory and gender schema theory.

Kohlberg’s theory of gender development

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development (see the cognition and development page for more details) argues that children’s thinking changes as they grow up. Kohlberg’s theory of gender development is based on this model, arguing that gender development occurs alongside general development in thinking that comes with age.

In the case of gender development specifically, Kohlberg (1966) identifies 3 stages: Gender identity, gender stability, and gender constancy.

After the child reaches gender constancy, they seek out and imitate role models who match their gender. For example, a boy may take an interest in football if he identifies with his father who is also interested in football.

AO3 evaluation points: Kohlberg's theory of gender

Strengths of Kohlberg’s theory:

- Evidence supporting Kohlberg’s theory: Several studies support a pattern of gender development in line with Kohlberg’s theory. For example, Thompson (1975) found that 76% of 2 year olds demonstrated gender identity but that this increased to 90 among 3 year olds, which is consistent with Kohlberg’s timeline. Similarly, Thompson and Bentler (1973) demonstrated that most children have gender stability by 4-6 years old. Finally, Slaby and Frey (1975) found that after children reach gender constancy they pay more attention to same-sex role models, which is in line with Kohlberg’s predictions.

- Holistic: Although Kohlberg’s theory is primarily a cognitive explanation of gender development, it is compatible with biological and social explanations. For example, Kohlberg describes how once a child achieves gender constancy they identify with and imitate same-sex role models, which is compatible with social learning explanations.

Weaknesses of Kohlberg’s theory:

- Conflicting evidence: Some researchers argue that children’s gender development happens earlier than Kohlberg’s theory suggests. For example, gender schema theory argues that children start behaving in gendered ways as early as 2 years old, whereas Kohlberg argues that children only start imitating same-sex role models after achieving gender constancy (at around 6 years old). The earlier development described by gender schema theory has some reseach support. For example, Bussey and Bandura (1992) found that children behave in gender-typical ways regardless of age and level of gender constancy.

- Methodological concerns: Kohlberg’s theory was based on interviews with children as young as 2 years old. However, it may be that the younger children had more sophisticated concepts of gender than they could express due to the fact that children are still learning to talk at that age. This raises questions about the validity of Kohlberg’s theory.

- Other factors: A truly holistic account of gender development will include all factors, such as biological and social influences. For example, Munroe et al (1984) observed a pattern of gender development in line with Kohlberg’s three stages across multiple different cultures, which suggests there are common biological processes underpinning these changes in thought.

Gender schema theory

Martin and Halverson (1981) and Bem (1981) argue that children start developing gender schema – mental frameworks to understand gender – at around 2-3 years old. For example, a boy might develop the schema that “dolls are a girl’s toy”. These schema are used to make sense of the world and also affect how the child behaves. For example, the boy will play with toy trucks and not dolls.

Martin and Halverson (1981) and Bem (1981) argue that children start developing gender schema – mental frameworks to understand gender – at around 2-3 years old. For example, a boy might develop the schema that “dolls are a girl’s toy”. These schema are used to make sense of the world and also affect how the child behaves. For example, the boy will play with toy trucks and not dolls.

This gender schema theory differs from Kohlberg’s theory in that it argues children behave in gendered ways from a much earlier age. Whereas Kohlberg argues that children start imitating gender-appropriate role models at around 6 years old (after reaching gender constancy), gender schema theory proposes that children start developing gender schemas from around age 2.

Over time, gender schemas develop along with other developments in thinking. For example, early schemas focus on the child’s own gender only, but by around age 8 children develop schemas for the opposite gender as well. Later, by the time the child is a teenager, they realise that a lot of the so-called rules about boys and girls are just social customs and so their gender schema become more flexible.

AO3 evaluation points: Gender schema theory

Strengths of Gender schema theory:

- Evidence supporting gender schema theory: Martin and Little (1990) observed that children aged 3-5 have stereotypical beliefs about which toys and clothes go with each gender, which suggests they have already developed gender schema by this age.

- Predictive power: In general, people are biased towards information that fits their pre-existing schema. So, if gender schema theory is correct, you would expect children to be biased towards information that fits their gender schema. Martin and Halverson (1983) found that children aged 5-6 were more likely to accurately remember gender-typical pictures (e.g. a boy playing with a train) and more likely to misremember non-stereotypical pictures (e.g. a girl sawing wood), which is in line with the predictions of gender schema theory.

Weaknesses of Gender schema theory:

- Conflicting evidence: Several studies suggest children demonstrate gender-typical behaviour before forming gender schema. For example, Alexander et al (2009) found boys aged 3-8 months looked at toy trucks more than toy dolls and that girls aged 3-8 months looked at toy dolls more than toy trucks. Similarly, Caldera et al (1989) found that children as young as 18 months display preferences for gender-typical toys. Further, Hassett et al (2008) found that rhesus monkeys – animals who clearly do not have gender schema! – also display preferences for gender-typical toys. These studies suggest factors other than cognitive schema (e.g. biology) influence gender development and that an interactionist explanation might be more appropriate.

- Schema may not change behaviour: Gender schema theory explains gender-typical behaviour as the result of gender schema but the link between the two is questionable. For example, many couples that value gender equality (i.e. couples without stereotypical gender schema) still typically organise roles according to stereotypes. This suggests that there is more to gender development than simply cognitive beliefs and schema.

Psychodynamic explanations of gender development

Psychodynamic explanations of gender development, like psychodynamic approaches to psychology in general, focus on unconscious conflicts between different aspects of the mind. The main example of this is Freud’s psychoanalytic theory.

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory explains behaviour as the result of conflicts between different parts of the mind: The id, the ego, and the superego (see the approaches page for more details).

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory explains behaviour as the result of conflicts between different parts of the mind: The id, the ego, and the superego (see the approaches page for more details).

According to Freud, childhood development involves resolving five conflicts and passing through five psychosexual stages. It is during the phallic psychosexual stage (3-5 years) where gender develops. This gender development follows a similar pattern for men and women:

- The child develops a sexual attraction to their opposite-sex parent and a dislike of their same-sex parent (for women this is known as the Electra complex and for men the Oedipus complex).

- The child resolves this conflict by identifying with the same-sex parent.

- By identifying with the same-sex parent, the child internalises the same-sex parent’s personality into their own, which settles their gender.

Oedipus complex

Resolution of the Oedipus complex (named after the mythical Greek king who accidentally killed his father and married his mother) is Freud’s explanation of male gender development.

Prior to the phallic psychosexual stage (3-5 years), a boy has no concept of his gender. Then, during the phallic stage, the boy develops an unconscious sexual desire for his mother. This desire leads to unconscious feelings of jealousy and hatred towards his father, because the father has what the boy desires (the mother). The boy’s id – the unconscious and instinctive part of the mind that is only concerned with pleasure – wants to kill the father in order to have the mother for himself.

But the boy’s ego – the practical part of the mind that mediates between the desires of the id and reality – recognises that the father is stronger than him. This leads to fear of the father. The boy thinks that, if his father discovers that he desires his mother for himself, the father will remove his penis (castration anxiety).

To resolve these conflicting desires and beliefs, the boy abandons the desire for his mother and identifies with the father. By identifying with the father, the boy incorporates and internalises the father’s personality into his superego. Internalising the father’s personality means also internalising the father’s masculine gender. The boy develops his gender by displacing the sexual desire for his mother onto other women.

Electra complex

Resolution of the Electra complex (named (by Carl Jung, not Freud) after the mythical Greek daughter of King Agamemnon who killed her mother) is Freud’s explanation of female gender development.

Prior to the phallic psychosexual stage (3-5 years), a girl has no concept of her gender. After she reaches this stage, the girl believes that the reason she does not have a penis is because she has been castrated. The girl desires a penis (penis envy) and so develops a desire for her father as he has what she wants. The girl also develops a dislike of her mother for two reasons: Firstly, because she blames the mother for taking her penis, and secondly, because she sees the mother as competition for her father’s love. However, the girl also loves her mother and fears losing her love if she discovers her desires for her father.

To resolve these conflicting desires, the girl represses her feelings of dislike for her mother and instead identifies with her. By identifying with the mother, the girl incorporates and internalises the mother’s personality into her superego. Internalising the mother’s personality means also internalising the mother’s feminine gender. The girl develops her gender by substituting her desire for a penis with a desire to have a baby.

AO3 evaluation points: Psychodynamic explanations of gender development

Strengths of psychodynamic explanations:

- Evidence supporting psychodynamic explanations: Freud (1909) used the case study of Little Hans as evidence to support the Oedipus complex. Hans saw a horse collapse in the street one day and after that incident developed an intense fear of horses. However, Freud claimed this fear of horses was actually a displaced fear of his father (‘black bits’ around the horse’s mouth representing his father’s moustache) in line with the Oedipus complex. In later therapy sessions, Hans described a dream in which a plumber replaced his penis with a bigger one, which Freud interpreted as Hans identifying with his father and overcoming his Oedipus complex. Hans overcame his fear of horses and went on to become a psychologically healthy adult.

Weaknesses of psychodynamic explanations:

- Methodological concerns: The Little Hans case study is a single example that involves a lot of subjective (and potentially biased) interpretation. It’s a bit of a stretch to conclude from such evidence that the Oedipus complex is a universal process of male gender development.

- Unscientific: Freud’s theories of gender development (as with Freud’s theories in general) are based on unconscious concepts such as the id. These concepts are difficult, if not impossible, to observe and measure. However, science is concerned with what is observable, measurable, and repeatable, and so by this standard Freud’s theories are unscientific. Further, because these unconscious processes cannot be observed and measured, Freud’s theories are accused of being unfalsifiable: There is no evidence that could disprove them.

- Conflicting evidence: Freud claimed that children have no concept of their gender prior to the phallic stage (3-5 years). However, several studies (e.g. those discussed in the gender schema theory and Kohlberg’s theory AO3 sections above) demonstrate that children are aware of their own gender much earlier than this.

- Gender bias: Freud’s theory is mainly focused on male gender development and can be said to demonstrate an androcentric bias. For example, both the Oedipus complex and the Electra complex assume the male perspective as the default and desirable: Male development focuses on the penis (and fear of losing it) whereas female development is characterised by a lack of and desire for a penis.

Social learning explanations of gender development

Social learning theory (see the approaches page for more details) explains gender as resulting from observation and imitation of gender role models. For example, a boy may observe and imitate his father’s behaviour. Gender-typical behaviours may then be reinforced. For example, a boy may be praised for gender-typical behaviour (e.g. “wow, you’re so strong!”) or punished for opposite-gender behaviour (e.g. “stop acting like a girl!”).

Role models can include things like parents, siblings, and peers but the syllabus focuses on gender role models in culture and the media specifically.

Media

Bandura and Bussey (1999) give several examples of how gender roles are portrayed in the media. For example, TV shows typically portray men as ambitious and having high-status jobs whereas women are typically portrayed as unambitious and occupying domestic roles or low-status jobs. Men are also portrayed as having greater agency (i.e. control over events), whereas women are more likely to be at the mercy of others. These stereotypes also exist in adverts, with women typically promoting food and beauty products and men promoting things like computers, cars, and financial products.

Bandura and Bussey (1999) give several examples of how gender roles are portrayed in the media. For example, TV shows typically portray men as ambitious and having high-status jobs whereas women are typically portrayed as unambitious and occupying domestic roles or low-status jobs. Men are also portrayed as having greater agency (i.e. control over events), whereas women are more likely to be at the mercy of others. These stereotypes also exist in adverts, with women typically promoting food and beauty products and men promoting things like computers, cars, and financial products.

There is evidence that these stereotypes influence gender roles. For example, McGhee and Frueh (1980) found a correlation between media exposure and stereotypical views of sex-roles. In other words, the more TV a child watches, the more likely they are to have stereotypical views about gender.

These studies support the social learning theory explanation of gender development: Children observe role models in the media, identify with those of the same gender, and imitate their gender-typical behaviour.

Culture

Comparing gender roles among different cultures can provide insights into how much gender is a social construct and how much it is a biological one: If gender roles are biological, you would expect different cultures to have the same gender stereotypes because human biology is basically the same across cultures. But if gender roles are socially constructed, you would expect greater variation between cultures because different cultures would create different social norms and values.

Mead (1935) studied gender roles among 3 different tribes in Papua New Guinea. She observed that many tribes had gender roles that differed from each other and from typical gender roles in Western cultures:

- Arapesh: Both the men and women were caring and peaceful (stereotypically female behaviour in Western cultures).

- Mundugumor: Both the men and women were aggressive and warlike (stereotypically male behaviour in Western cultures).

- Tchambuli (Chambri): Women were the workers (e.g. catching fish) and organised society, while men decorated themselves (opposite gender roles to those typical in Western cultures).

These differences between cultures suggest that gender roles are culturally, rather than biologically, determined.

However, Mead’s interpretations have been criticised. For example, Errington and Gewertz (1989) also studied the Tchambuli (Chambri) tribe but found no evidence to support the gender roles described by Mead. Further, several studies (see AO3 evaluation points below) have found gender roles are generally consistent across different cultures.

AO3 evaluation points: Social learning explanations of gender development

Strengths of social learning explanations:

- Evidence supporting social learning explanations: Studies support social learning explanations of gender – in the media, the culture, and through other social avenues – to differing degrees.

- Media: McGhee and Frueh (1980) and Bandura and Bussey (1999) demonstrate correlations between stereotypical representations of gender in the media and stereotypical views on gender, which suggests the media plays a role in teaching gender stereotypes.

- Culture: Although Mead (1935) supports social learning explanations based on culture, other studies question her findings (see weaknesses below).

- Peer influence: More generally, many studies (e.g. Bussey and Bandura (1992) and Langlois and Downs (1980)) have demonstrated that young children enforce gender roles (e.g. by bullying children for playing with toys of the ‘wrong’ gender), which supports social learning explanations based on peer influence.

- Explanatory power: Social learning theory is able to explain changing gender stereotypes. For example, a higher percentage of women now work in industries like science and engineering – fields that were once thought of as typically male – than in the past. This could be explained by the media, as women are more likely to be portrayed in such roles than in previous decades.

Weaknesses of social learning explanations:

- Conflicting evidence: Several studies have found similar gender roles exist cross-culturally, contradicting Mead (1935). For example, Barry et al (1957) looked at 110 different cultures and found almost all of them saw nurturing and obedience as feminine traits and self-reliance and achievement-striving as masculine traits. Similarly, Whiting and Edwards (1988) looked at children in 6 cultures (the USA, Mexico, Japan, India, Kenya, and the Philippines) and found that girls were generally more caring than boys and that boys were generally more aggressive than girls. These studies weaken support for cultural explanations of gender development.

- Questions about temporal validity: The studies described above linking media consumption and gender-stereotypical views were conducted in the 1980’s and 1990’s. However, modern portrayal of men and women in the media is much less gender-stereotypical than it was when these studies were conducted. Further, the types of media that children consume has changed since these studies, with social media likely playing a bigger role than television. As such, the findings of these studies may lack temporal validity, with the role of the media on gender development being much different than it once was.

- Other factors: As always, you can take an interactionist stance and argue that social learning plays a role in gender development but is not a complete explanation of it. For example, you could argue that there is a biological basis to gender roles that gets amplified and exaggerated by social learning.

Atypical gender development

Gender dysphoria

Gender dysphoria (previously referred to as gender identity disorder) is a condition where a person’s biological sex does not match their psychological gender. For example, somebody born biologically male (i.e. with XY chromosomes) may be psychologically female.

Gender dysphoria often begins in childhood. It can cause symptoms such as anxiety and depression as the person feels uncomfortable in a body that is the ‘wrong’ sex. To help reduce these feelings of discomfort, the person may take steps to make their outer appearance align with their inner gender. For example, a male-to-female transgender person may wear gender-typical female clothes, take feminising hormones (estrogen), and undergo gender reassignment surgery.

The syllabus looks at biological and social explanations of gender dysphoria.

Biological explanations of gender dysphoria

Biological explanations of gender dysphoria include genetics, hormones, and brain structures. These different biological factors interact with one another and so cannot easily be separated. For example, a person’s genetics influence their brain structure.

Genetics

As always, twin studies are a useful way to determine the extent to which a condition is caused by genetic factors. If gender dysphoria is more common among both identical twins (who share 100% of their genes) than both non-identical twins (who only share 50% of their genes), this would suggest genetics play a role.

- Diamond (2013) combined a survey of transgender twins with a review of published studies on transgender twins. Concordance rates for gender dysphoria among identical male and identical female twin pairs were 33.3% and 22.8% respectively. In contrast, the concordance rate among non-identical twins (male or female) was only 2.6%. The higher concordance among identical twins than non-identical twins supports the existence of a genetic component to gender dysphoria.

- Coolidge et al (2002) analysed a sample of 314 twin children (96 identical pairs and 61 non-identical pairs) and estimated that gender dysphoria is 62% caused by genetics and 38% by non-shared environmental experience.

- Beijsterveldt et al (2006) analysed a sample of around 14,000 twin children and found concordance rates of cross-gender behaviour were higher among identical than non-identical twins. The researchers estimate that gender dysphoria is 70% explained by genetics.

In general, twin studies support a genetic basis of gender dysphoria. This genetic basis is further supported by gene association studies. For example, Hare et al (2009) analysed gene samples from 112 male-to-female transgender people and 258 controls, finding that gender dysphoria is correlated with differences in AR (androgen receptor) genes. In a gene association study of female-to-male transgender people, Bentz et al (2008) found gender dysphoria was correlated with the CYP17 gene. These studies suggest gender dysphoria is caused by different genes depending on whether the person is born biologically male or female.

Hormones

Hormonal explanations of gender dysphoria focus on prenatal (i.e. in the womb) hormone levels. It’s difficult to measure (and unethical to alter) prenatal hormone levels, but some evidence suggests prenatal hormones contribute to gender dysphoria. For example:

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia causes increased testosterone exposure in the womb. Erickson-Schroth (2013) found that at least 5.2% of biological females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia develop gender dysphoria, which is much higher than average. This suggests that prenatal testosterone exposure increases the incidence of gender dysphoria in biological females.

- Some studies suggest prenatal hormone levels affect finger length ratios (2D:4D digit ratio). A meta-analysis by Siegmann et al (2020) found male-to-female transgender people had higher 2D:4D ratios than male controls, but found no differences between female-to-male transgender people and female controls. This suggests prenatal hormones may contribute to gender dysphoria in biological males.

Prenatal hormones affect brain development (see above for examples), which may explain the mechanism through which hormones cause gender dysphoria. However, the role of prenatal hormones in gender dysphoria is disputed (see AO3 evaluation points below).

Brain structures

Several studies have found correlations between gender identity and brain structure, suggesting a role in gender dysphoria. In particular, research has focused on an area of the brain known as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BSTc), which is typically 40% larger in males than females. For example:

- Zhou et al (1995) used post-mortems to compare the brains of 6 male-to-female transgender people with cisgender male and female controls. The BSTc regions of the MtFs were closer in size to cisgender females than males, suggesting they had female brain structures.

- Kruijver et al (2000) compared the number of neurons in the BSTc regions of transgender people with cisgender people. The researchers found that MtF trans people had similar numbers of neurons as cisgender females and that FtM trans people had similar numbers of neurons to cisgender males.

Another area of the brain associated with gender identity is the interstitial nucleus of the anterior hypothalamus (INAH3). Males typically have twice as many neurons in this region as females, but post-mortems by Garcia-Falgueras and Swaab (2008) found MtFs had neuron numbers similar to female controls and FtMs had neuron numbers similar to male controls.

AO3 evaluation points: Biological explanations of gender dysphoria

Strengths of biological explanations:

- Evidence supporting biological explanations: See studies above (don’t worry, you don’t have to remember them all – they’re just examples). In general, the studies above support a genetic and neural basis of gender dysphoria, but the exact role of hormones is less clear.

Weaknesses of biological explanations:

- Conflicting evidence:

- Genetics: Although twin studies support a role for genetics in explaining gender dysphoria, the fact that concordance rates among identical twins are much less than 100% suggests that other factors (e.g. social explanations) play a role too.

- Hormones: A meta-analysis by Voracek et al (2018) found differences in 2D:4D ratios between transgender and cisgender people were small or non-existent, contradicting Siegmann et al (2020) and weakening support for the role of prenatal hormone exposure in explaining gender dysphoria.

- Brain structures: Hulshoff Pol et al (2006) used brain scans to measure the brains of transgender people before and after cross-sex hormone therapy. The researchers found that hormone therapy changed the size of the BSTc. This suggests differences in brain structures may be an effect of hormone therapy rather than a cause of gender dysphoria.

- Methodological concerns:

- Genetics: Being a twin is somewhat rare and gender dysphoria is rarer still. As such, the sample size for twin studies of gender dysphoria is often small, which means the findings are less likely to be valid. Further, there is the general methodological issue of twin studies that it is difficult to separate genes and environment: Identical twins are more likely to be treated similarly than non-identical twins. This more similar environment may partly explain the higher concordance rates for gender dysphoria among identical twins than non-identical twins, with the role of genetics being overestimated.

- Hormones: The reliability and validity of 2D:4D ratio as a way to measure prenatal hormone levels is disputed. As such, any studies that use 2D:4D ratio to link gender dysphoria with prenatal hormone levels may not be valid.

- Other factors: Reducing gender dysphoria to biology could be overly reductive and may ignore the importance of other factors such as cognitions and social explanations.

Social explanations of gender dysphoria

Social explanations of gender dysphoria explain gender dysphoria as learned from the environment. This includes behaviourist explanations, such as operant conditioning, as well as social learning theory.

Social learning theory would say that gender dysphoria is caused by children observing and imitating role models of the opposite sex. For example, a young boy might observe his mother receiving compliments on her dress (vicarious reinforcement) and imitate this behaviour. This cross-gender behaviour may also be reinforced via operant conditioning. For example, adults may encourage or praise the boy for wearing a dress. This creates a conflict between the boy’s biological sex and psychological gender, leading to gender dysphoria.

AO3 evaluation points: Social explanations of gender dysphoria

Strengths of social explanations:

- Evidence supporting social explanations: Earlier research focused on social explanations of gender dysphoria (e.g. Rekers and Lovaas (1974)), but the general consensus is that social explanations of gender dysphoria are less important than biological ones. However, social factors still likely play a role, as biological explanations of gender dysphoria are incomplete. For example, concordance rates for gender dysphoria among identical twins are much less than 100%, which opens the door for factors other than biology to explain gender dysphoria.

Weaknesses of social explanations:

- Conflicting evidence: Transgender people often face many social difficulties (e.g. prejudice and bullying) and if social explanations of gender dysphoria are correct this should discourage cross-gender behaviour. However, the fact that many transgender people insist on living as their preferred gender despite these negative consequences suggests there is a deeper, biological, reason for gender dysphoria.

- Other factors: There is quite a lot of evidence supporting biological explanations of gender dysphoria (see studies above) and so even if there is a social dimension to gender dysphoria it is likely these other factors play a role too. This suggests an interactionist approach may be more appropriate.

<<<Issues and debates

Schizophrenia>>>

or:

Eating behaviour>>>

or: