Overview – Psychopathology

Psychopathology is the study of mental disorders and conditions that are considered psychologically abnormal. Defining ‘abnormal’ is a topic in itself, with the syllabus mentioning 4 definitions of abnormality: deviation from social norms, failure to function adequately, statistical infrequency, and deviation from ideal mental health.

The A level psychology syllabus lists 3 specific mental disorders. Each of these mental disorders is approached from a different psychological viewpoint – both in terms of explanation and treatment:

- Phobias (explained from a behaviourist perspective)

- Depression (explained from a cognitive perspective)

- OCD (explained from a biological perspective)

Note that these are not the only valid psychological approaches to these disorders. For example, phobias can be treated biologically (e.g. with drugs) and OCD can be treated cognitively (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy). These alternative approaches can be used to evaluate the approach listed in the syllabus.

Definitions of abnormality

The syllabus mentions 4 candidate definitions of psychological abnormality:

- Deviation from social norms

- Failure to function adequately

- Statistical infrequency

- Deviation from ideal mental health

Each of these definitions has various strengths and weaknesses, which are covered in the AO3 evaluation points below.

Deviation from social norms

Social norms are the expected rules of behaviour in society. They differ between cultures and between the same culture at different periods in time. Some typical examples of social norms include:

- Wearing clothes in public

- Saying “thank you” when someone does something for you

- Respecting people’s personal space

We can define abnormality as behaviour that deviates from these social norms. For example, going up and touching random strangers or walking around naked is abnormal.

The degree to which a behaviour is abnormal depends on how extreme the deviation is and how important the norm is. For example, not saying “thank you” might be somewhat abnormal – but it’s not dangerous, just rude. However, going up to and touching random strangers is a more extreme deviation of a more important rule and so may justify intervention from other people to stop this behaviour.

AO3 evaluation points: Deviation from social norms definition of abnormality

Strengths of the deviation from social norms definition:

- The social dimension of this definition can help both the abnormal individual and wider society. For example, intervention by society may protect citizens from the potentially dangerous behaviours of abnormal individuals. Further, intervention may also help the abnormal individual (who may not be able to help themself) by teaching them to interact successfully in society and avoid potentially dangerous consequences of abnormal behaviour.

- Social norms are flexible to account for the individual and situation. For example, throwing tantrums and hitting people is socially normal for a toddler, but would be a sign of mental disorder in adulthood. Similarly, walking around naked in your house might be normal, but walking around naked in the street would be a sign of mental disorder.

Weaknesses of the deviation from social norms definition:

- Social norms are not objective facts that definitively say which behaviours are most healthy, but instead are subjective (and somewhat arbitrary) rules created by other people.

- Social norms change over time and so what is considered a mental disorder today might not be in the future. For example, homosexuality was diagnosed as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association until 1973.

- Social norms vary between cultures. For example, it is normal for someone to blow their nose in public, whereas in India such behaviour would go against social norms.

- A person who deviates from social norms may simply be eccentric rather than psychologically abnormal. For example, it goes against social norms to dress in 18th century clothes today, but it’s not exactly a mental disorder – the person might just like to dress that way.

Failure to function adequately

Another definition of abnormality is failure to function adequately. This means a person is unable to navigate everyday life or behave in the necessary ways to live a ‘normal’ life. For example, failure to function adequately would prevent a person from having successful interpersonal interactions or get and keep a job.

Rosenhan and Seligman (1989) identify various features of dysfunction, including:

- Personal distress (e.g. anxiety, depression, excessive fear)

- Maladaptive behaviour (i.e. behaviour that prevents the person achieving goals)

- Irrationality

- Unpredictability

- Discomfort to others

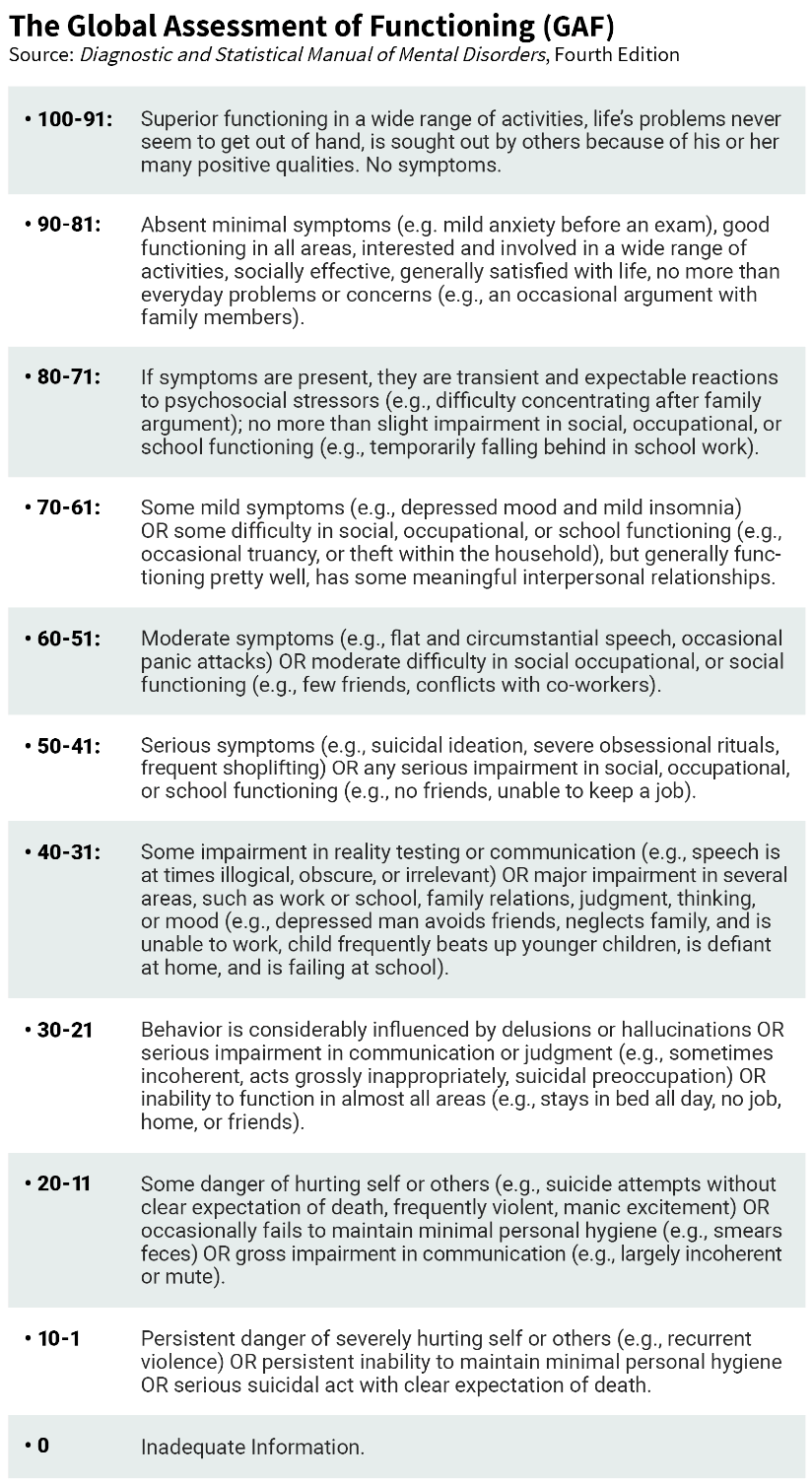

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale provides a way to quantify (from 0 to 100) the extent to which a mental disorder affects an individual’s ability to function adequately. A person who scores highly (e.g. 80+) will have few if any symptoms that prevent their ability to function, whereas a person with a very low score (<20) will struggle in society and may even be a danger to themself or others.

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale provides a way to quantify (from 0 to 100) the extent to which a mental disorder affects an individual’s ability to function adequately. A person who scores highly (e.g. 80+) will have few if any symptoms that prevent their ability to function, whereas a person with a very low score (<20) will struggle in society and may even be a danger to themself or others.

AO3 evaluation points: Failure to function definition of abnormality

Strengths of the failure to function definition:

- The GAF provides a practical and measurable way of quantifying abnormality.

- The majority of people who seek clinical help for psychological disorders do so because they believe the disorder is affecting their ability to function normally. So, this definition is well-supported by the individuals themselves who suffer from mental disorders.

Weaknesses of the failure to function definition:

- Not everyone with a mental disorder is unable to function in society. For example, there have been many instances of serial killers who managed to maintain a normal – or even highly successful – life despite being psychopaths. The fictional character of Patrick Bateman in American Psycho illustrates this.

- Not everyone who is unable to function is suffering from a mental disorder. In some contexts, psychologically healthy people may (temporarily) be unable to function adequately. For example, a person who has just lost a close friend or relative may be unable to go to work or have fun with friends due to the grief they are feeling.

- What counts as failure to function adequately may differ between cultures.

Statistical infrequency

The statistical infrequency definition of abnormality is a mathematical one. It defines abnormality as statistically rare characteristics and behaviours. The further a characteristic or behaviour is from the mathematical average, the more rare or statistically infrequent it is.

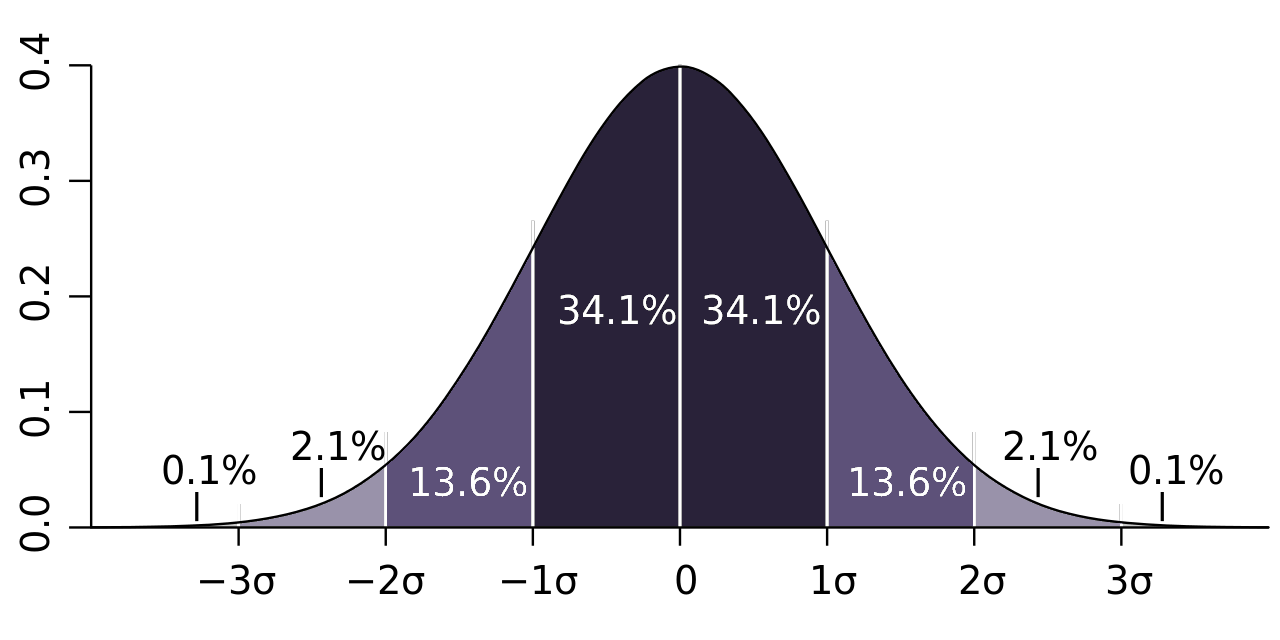

Statistical frequency can be plotted on a histogram like the one below:

The average here is indicated by 0 on the X-axis. The other figures indicate standard deviations (σ) from this average. The more a figure deviates from the average, the rarer it is.

For example, 68.2% of people – the majority – will be within 1 standard deviation of this average (34.1% above and 34.1% below). It is statistically more rare to be above or below 1 standard deviation from the average, and much rarer still to be more than 2 standard deviations from the average.

Many psychological traits and behaviours can be quantified and plotted on a graph like the one above. For example, intelligence can be quantified by IQ tests. The average IQ is 100, and most people will have an IQ within 1 standard deviation of this (i.e. between 85 and 115). An IQ above 130 or below 70 is statistically infrequent – it occurs in only around 2% of people – and so, according to this definition, would be considered psychologically abnormal.

AO3 evaluation points: Statistical infrequency definition of abnormality

Strengths of the statistical infrequency definition:

- Statistical infrequency provides a clear and objective way of determining whether something is abnormal or not. It is not just the subjective opinion of one person, but something that can be measured and quantified.

- Statistical infrequency does not imply any value judgements, i.e. whether something is good or bad. For example, homosexuality has historically been defined as a mental disorder – but not because it is bad or wrong, but because it is statistically rare compared to heterosexuality.

- Statistical infrequency is a good measure for many psychological disorders. For example, intellectual disability has historically been defined as having an IQ lower than 70 (2 standard deviations below the mean).

Weaknesses of the statistical infrequency definition:

- Infrequency does not always mean abnormality or mental disorder. For example, having an IQ above 140 is statistically infrequent, but it’s not a mental disorder and is actually quite desirable.

- And vice versa: Abnormality does not necessarily mean infrequency. For example, ‘abnormal’ mental conditions such as anxiety and depression are statistically quite common.

- Some psychological disorders are difficult to measure objectively and thus difficult to quantify as statistically infrequent. For example, how do you quantify how depressed or anxious someone is in order to determine whether they are statistically infrequent?

Deviation from ideal mental health

Another definition of abnormality is deviation from ideal mental health.

But in order to understand what it means to deviate from ideal mental health, we first need to define what ideal mental health is. Jahoda (1958) identified 6 features of ideal mental health:

| A positive attitude toward oneself | Being happy with who you are and having self-respect and self-esteem. |

| Self-actualisation | Achieving personal growth and progress, realising one’s potential. |

| Autonomy | Being independent, self-reliant, and able to make decisions for yourself. |

| Ability to resist stress | Being able to effectively deal with the challenges of life without excessive stress. |

| An accurate perception of reality | Being realistic and objective about oneself and the external world. |

| Mastery of environment | The ability to successfully navigate work, social, and other situations |

Someone with ideal mental health would tick all 6 of these boxes. However, if a person fails to tick most of these boxes, or deviates significantly from one of them (e.g. they constantly hallucinate pink elephants and thus do not have an accurate perception of reality), they would be classified as abnormal according to the deviation from ideal mental health definition.

AO3 evaluation points: Deviation from ideal mental health definition of abnormality

Strengths of the deviation from ideal mental health definition:

- The holistic description of ideal mental health focuses on the entire person rather than atomised elements, which may provide a more effective and long-lasting means of treating mental disorders. For example, a person with depression might have low self-esteem and not be achieving self-actualisation. Addressing the overall deviation from mental health might be a more effective treatment avenue than focusing on specific symptoms in isolation.

- The deviation from ideal mental health definition provides a positive goal to strive towards: Rather than focusing on what is ‘abnormal’ or ‘undesirable’, this definition focuses on what is optimal and desirable and aims towards that.

Weaknesses of the deviation from ideal mental health definition:

- Too idealistic. Very few people meet all of Jahoda’s 6 criteria all the time. For example, many people have times when they lack self-esteem, and very few people are self-actualising all the time. So, according to this defintion, most people are psychologically unhealthy or ‘abnormal’.

- Jahoda’s criteria are somewhat subjective and hard to measure. For example, it is hard to quantify how much a person is self-actualising, or the extent to which they are able to master their environment. There are methods for measuring such characteristics (e.g. patient self-reports) but these may be unreliable, as each individual is likely to have different standards.

- What is understood by ideal mental health may differ between cultures. For example, Jahoda mentions autonomy as an important characteristic of ideal mental health, but more collectivist cultures may view individual autonomy as undesirable.

Phobias

A phobia is an anxiety disorder characterised by extreme and irrational fear towards a stimuli. Examples of phobias include:

- Arachnophobia: fear of spiders

- Aerophobia: fear of flying in aeroplanes

- Agoraphobia: fear of leaving one’s house

- Social phobias, such as fear of crowds or public speaking

Characteristics of phobias

Emotional characteristics: It is natural to feel some fear in response to potential danger. But people with phobias experience extreme fear that is uncontrollable and disproportionate to the situation.

Behavioural characteristics: Screaming, crying, freezing, or running away from the feared stimuli. A phobic person will typically try to avoid the feared stimuli – for example, a person with aerophobia might stay away from airports.

Cognitive characteristics: Most people with phobias recognise that their fear is irrational and disproportionate. However, this recognition does little to reduce the fear the phobic person feels.

Behaviourist approach to phobias

There are many competing and complementary approaches to psychology, including behaviourism, the cognitive approach, and the biological approach. The syllabus focuses on the behaviourist approach to phobias, but other approaches can serve as a means to evaluate this approach.

Behaviourist explanations of phobias

The behavioural approach (behaviourism) analyses phobias based on external observations of environmental stimuli and behavioural responses (rather than e.g. the underlying thought processes). The two-process model explains how phobias are developed and maintained through behavioural conditioning.

The two-process model

The two-process model explains phobias as:

- Acquired through classical conditioning, and

- Maintained through operant conditioning.

Classical conditioning (acquisition of phobia)

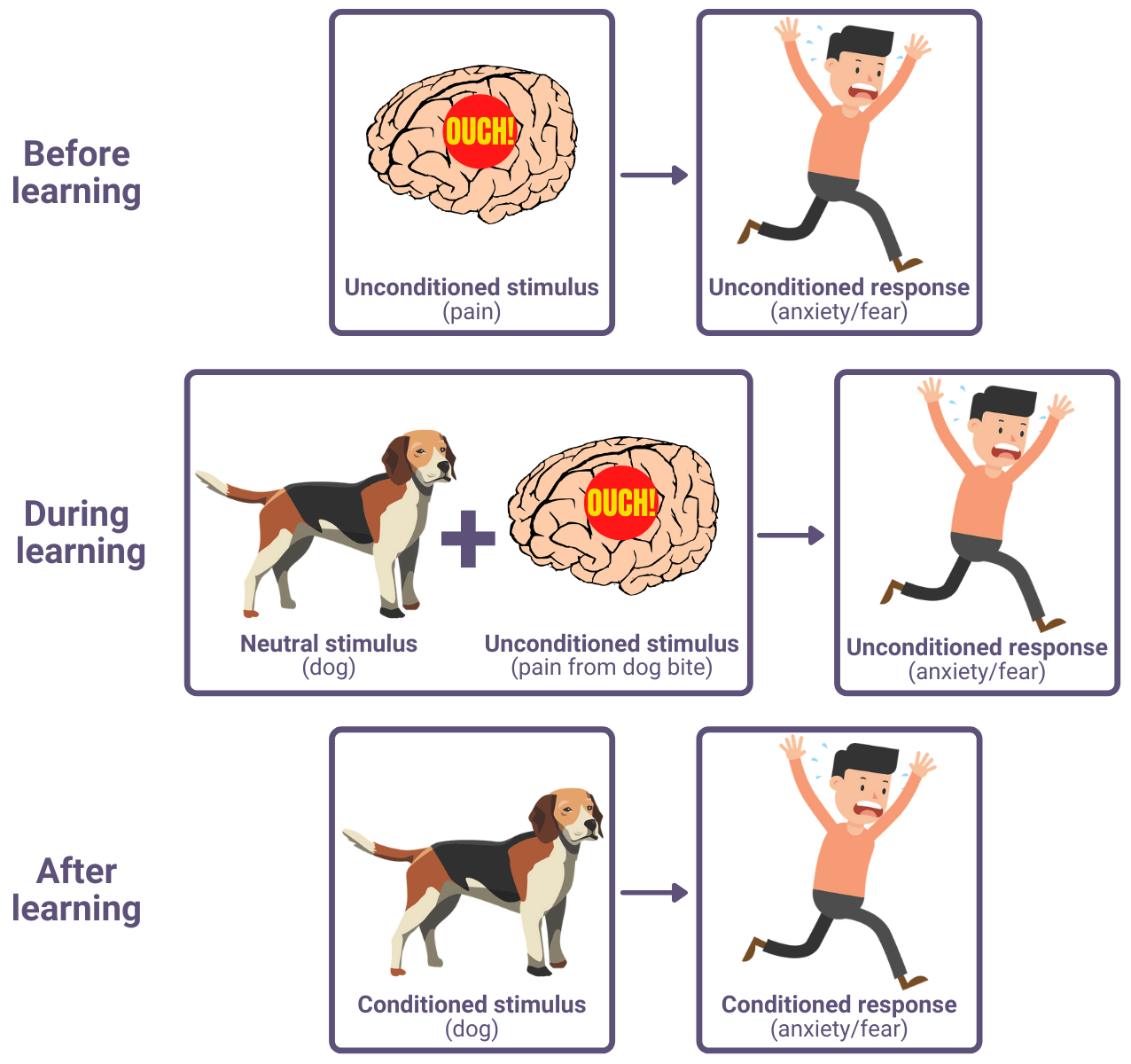

An example of how a person could be conditioned to develop a phobia of dogs is as follows:

Humans naturally fear pain, and so a fear response to pain is unconditioned. But when this natural (unconditioned) response is associated with a neutral stimulus (e.g. a dog) through experience (e.g. a dog biting them), then a person can become conditioned to associate the response (fear) with the stimulus (dogs). This is an example of classical conditioning, which is based on the work of Ivan Pavlov.

An example of this humans can be found in Watson & Rayner (1920). In their experiment, an 11 month old baby – ‘Little Albert’ – was given a white rat to play with. Albert did not demonstrate a fear response towards the rat initially, but the researchers then made a loud noise which frightened Albert. This process was repeated several times, after which Albert demonstrated fear behaviour (e.g. crawling away, whimpering) when presented with the rat (and similar stimuli such as a rabbit and a fur coat) even without the loud noise.

Operant conditioning (maintenance of phobia)

Classical conditioning is outside a person’s conscious control – the conditioned response develops automatically. In contrast, operant conditioning occurs in response to behaviour, which is under a person’s control. If a person behaves in a way that produces a pleasurable outcome, then that behaviour is positively reinforced, making the person more likely to behave that way again. Similarly, if a person behaves in a way that reduces an unpleasant feeling, then that behaviour is negatively reinforced, also making them more likely to behave that way again.

Within the two-process model, this sort of operant conditioning explains how phobias are maintained. Returning to the phobia of dogs example: A person with a conditioned phobia of dogs will feel anxiety in the presence of dogs. And so, avoiding dogs (e.g. by running away from them or avoiding parks) will lessen this anxiety, which negatively reinforces these dog-avoiding behaviours. This pattern of behaviour and reward via operant conditioning reinforces and thus maintains the phobia.

AO3 evaluation points: Behaviourist explanations of phobias

Strengths of behaviourist explanations of phobias:

- Supporting evidence: In addition to Watson and Rayner (1920) above, there are several case studies that support the behaviourist explanation of phobias. For example, King et al (1998) describe several case studies of children who acquired phobias after a traumatic experience.

Weaknesses of behaviourist explanations of phobias:

- Alternative explanations: Rather than focusing on behaviours, the cognitive approach explains phobias in terms of thought processes. For example, there is evidence that phobic people may have an attentional bias (i.e. disproportionate focus of thought) towards the scariest features of the stimuli (e.g. a dog’s teeth or a spider’s venom).

- Not everyone who has an unpleasant experience at the same time as a neutral stimulus goes on to develop a phobia. For example, a person who gets bitten by a dog will not always develop a phobia of dogs. This weakens the behaviourist claim that phobias are acquired through classical conditioning.

Behaviourist treatment of phobias

Systematic desensitisation

One behavioural treatment for phobias is systematic desensitisation. This involves gradually increasing exposure to the feared stimuli until it no longer induces anxiety. For example, someone with a fear of spiders (arachnophobia) may initially be asked to imagine spiders and guided through relaxation strategies until they can stay calm. Then, the process may be repeated with pictures of spiders, then real-life spiders in cages, and then repeated again with the subject actually holding a spider.

Systematic desensitisation is another example of classical conditioning: the subject is conditioned to associate the object with relaxation instead of anxiety.

An example of successful treatment of phobia using systematic desensitisation is described in Jones (1924). A 2 year old boy – Peter – had a phobia of white rats and similar stimuli. Jones was able to remove Peter’s phobia over several sessions with him by progressively increasing his exposure to a white rabbit.

Flooding

Another behavioural approach to treating phobias is flooding. Whereas systematic desensitisation increases exposure step-by-step, flooding involves exposing the subject to the most extreme scenarios straight away. For example, returning to arachnophobia, the subject would be placed in direct contact with spiders until their anxiety response subsides.

The idea behind flooding is that extreme anxiety cannot be maintained indefinitely. Eventually, the fear subsides and, in theory, the phobia.

An example of successful treatment of phobia using flooding is described in Wolpe (1969). A girl with a phobia of cars was driven around in a car for four hours until she calmed down and her phobia disappeared.

AO3 evaluation points: Behaviourist treatment of phobias

Strengths of behaviourist treatment approaches of phobias:

- Supporting evidence: See studies above.

Weaknesses of behaviourist treatment approaches of phobias:

- Behavioural treatment works better with some phobias than others. For example, simple phobias such as of dogs or spiders are more amenable to behavioural treatments than social phobias. This suggests that not all phobias can be explained or treated in behaviourist terms.

- Behaviourist treatment of phobias – particularly flooding – may raise ethical concerns. For example, forcing a girl with a phobia of cars into one for four hours may be seen as cruel.

Depression

Depression is a mood disorder characterised by feelings of low mood, loss of motivation, and inability to feel pleasure.

There are two kinds of depression: unipolar and bipolar. Bipolar depression (sometimes called manic depression) is characterised by the descriptions below + occasional manic symptoms whereas unipolar depression is characterised by these symptoms only with no manic episodes.

There are two kinds of depression: unipolar and bipolar. Bipolar depression (sometimes called manic depression) is characterised by the descriptions below + occasional manic symptoms whereas unipolar depression is characterised by these symptoms only with no manic episodes.

Characteristics of depression

Emotional characteristics: People with depression experience persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness. This low mood may come and go in cycles lasting months or years. Depression is also typically accompanied by feelings of worthlessness and a lack of enthusiasm.

Behavioural characteristics: Low energy, reduced activity, and reduced social interaction. Depressed people may also have irregular sleep patterns (either sleeping too much or too little (insomnia)) and gain or lose weight from over- or under-eating.

Cognitive characteristics: Depressed people may have exaggerated or delusional negative thoughts about themselves and what people think of them. They may have difficulty concentrating and remembering things. A depressed person may also regularly think about death and suicide.

Cognitive approach to depression

There are many competing and complementary approaches to psychology, including behaviourism, the cognitive approach, and the biological approach. The syllabus focuses on the cognitive approach to depression, but other approaches can serve as a means to evaluate this approach.

Cognitive explanations of depression

The cognitive approach analyses depression in terms of irrational and undesirable thoughts and thought processes (rather than e.g. the behaviours that result from these thought processes). The syllabus lists two cognitive explanations of depression: Beck’s negative triad and Ellis’ ABC model.

The cognitive approach analyses depression in terms of irrational and undesirable thoughts and thought processes (rather than e.g. the behaviours that result from these thought processes). The syllabus lists two cognitive explanations of depression: Beck’s negative triad and Ellis’ ABC model.

Example question: Discuss cognitive explanations of depression. [16 marks]

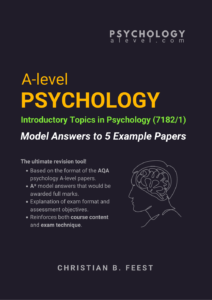

Beck’s negative triad

Beck (1979) argues that depression is characterised by a negative triad of beliefs about the self, the world, and the future:

He argues that this negative triad results from and is maintained by two cognitive processes:

Schema are patterns of thought – shortcuts/generalisations/frameworks – that are learned from experience to help make sense of the world and categorise information. Beck argued that experiences in childhood, such as criticism or failure to meet expectations, can cause depression-prone individuals to develop negative schema (i.e. a negative lens through which the individual views themself and the world). For example, experiences of failure in childhood may lead an individual to develop an ineptness schema whereby they constantly expect to fail.

These negative schema are caused by and amplify cognitive biases. Biases are systematic deviations from an accurate perception of reality in favour of some less accurate interpretation. For example, a person who loses a game of chance may falsely interpret this as proof that he is simply an unlucky person.

Together, these negative schema and cognitive biases maintain a negative triad of depressive beliefs about the self, the world, and the future.

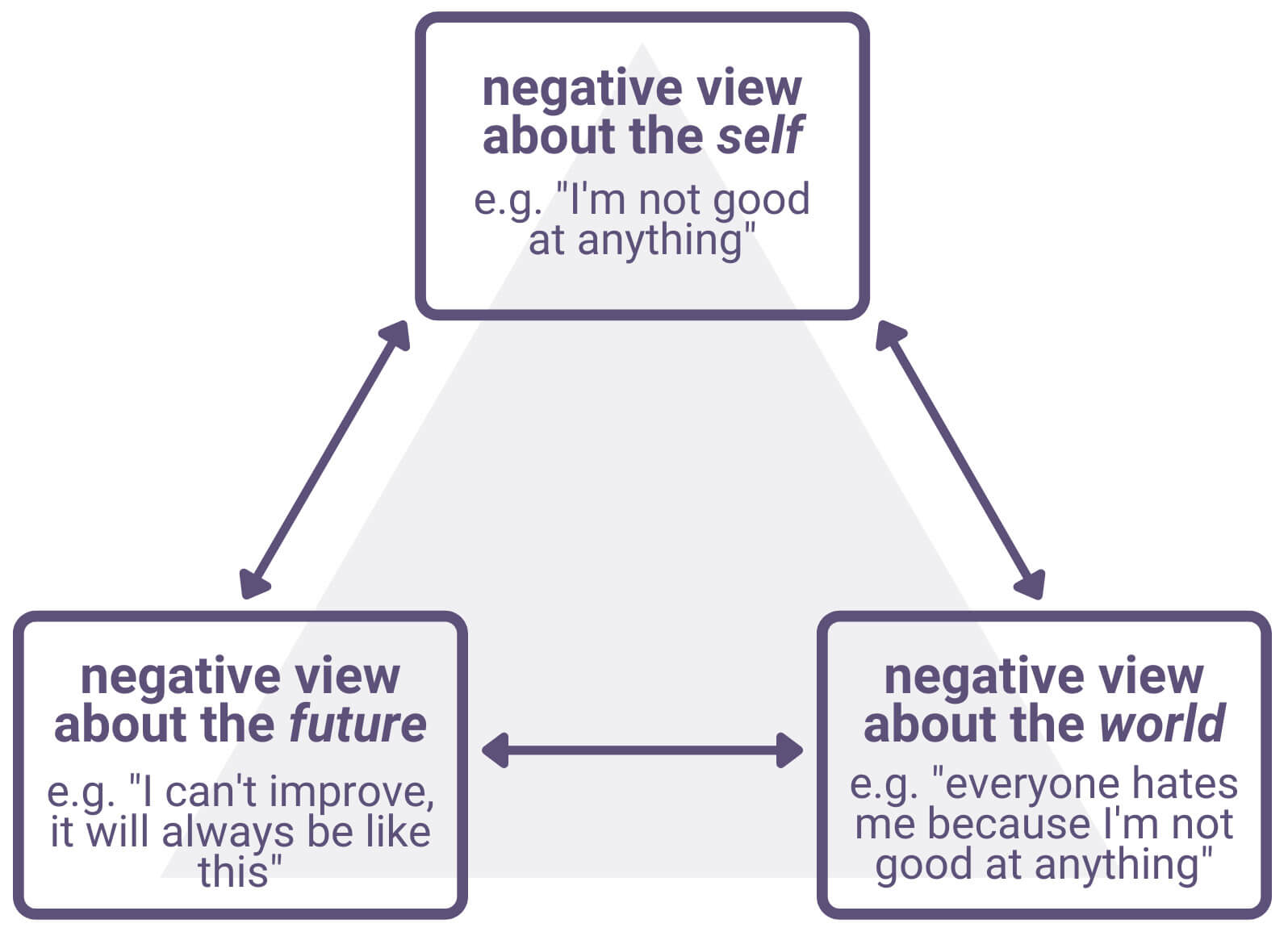

Ellis’ ABC model

Ellis (1962) argued that depression results from irrational interpretation of negative events, rather than the negative events themselves. He explains this process using the ABC model of activating event, belief, and consequence.

According to Ellis, we all have assumptions and beliefs (think schema) about ourselves and the world. With depressed people, though, these beliefs are often irrational and this leads them to interpret events (activating events) in an unrealistic way that causes a negative emotional reaction (consequence).

Again, it is not the activating event itself that causes the negative emotional consequence, but the irrational belief through which the activating event is interpreted.

AO3 evaluation points: Cognitive explanation of depression

Strengths of cognitive explanations of depression:

- Supporting evidence: Several studies support cognitive explanations of depression. For example, Koster et al (2005) conducted an experiment where participants were shown positive, negative, and neutral words on a screen and then got them to say where the words appeared on the screen. The depressed participants focused on the negative words more than the controls. In another study, Boury et al (2001) observed that depressed participants consistently misinterpreted facts and experiences in a negative way, supporting the cognitive explanation that depression is caused by biased and irrational thought processes. Also, the fact that cognitive approaches to treatment are effective (see below) suggests the cognitive explanations underlying these treatments are accurate.

Weaknesses of cognitive explanations of depression:

- Biological explanation of depression: Wender et al (1986) found that adopted children with depression were 8 times more likely to have biological parents who also had depression. This suggests there is a strong genetic/biological component to depression (rather than simply a cognitive explanation), as the children inherited the depression even though they were raised in a completely different environment to their biological parents. In other words, the children can’t have learned the depressed thought patterns of their biological parents because they weren’t raised by them.

- Behavioural explanation of depression: Lewinsohn (1974) argued that successive negative life experiences can cause depression. This suggests that depression is learned from the environment, and that negative thoughts could be an effect of depression rather than the cause (as the cognitive explanation claims). Kanter et al (2008) argue that behavioural approaches are typically overlooked in explaining and treating depression, but that behaviourism alone cannot adequately explain depression.

- Depressive realism: Alloy and Abramson (1988) argue that, rather than suffering from inaccurate or irrational beliefs, depressed people actually have a more accurate worldview than non-depressed people. A meta-analysis by Moore and Fresco (2012) found some support for the depressive realism hypothesis, but only in some situations.

Cognitive treatment of depression

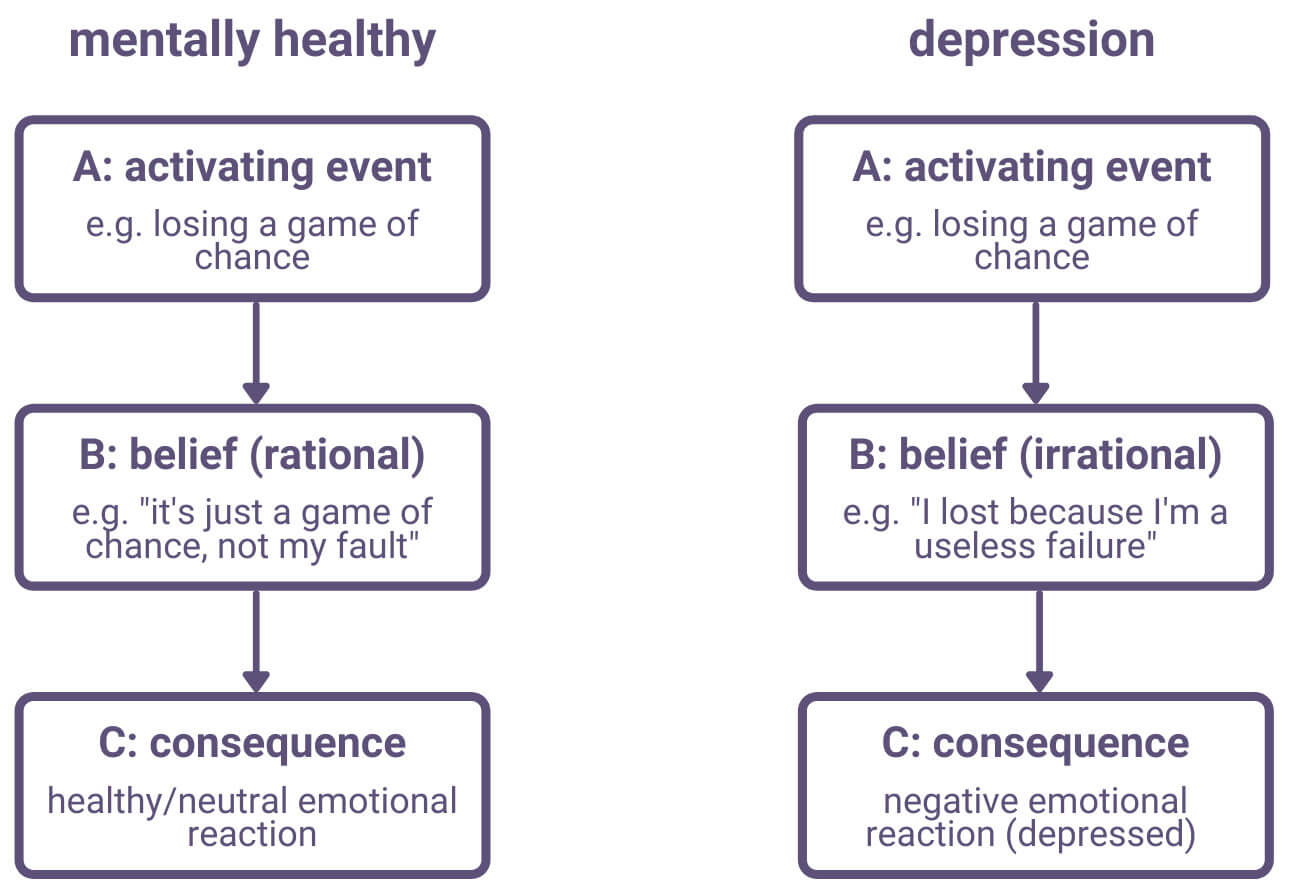

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

The cognitive approach sees depression as caused by negative, irrational, and maladaptive thought patterns. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) seeks to treat depression by identifying these depressed thought patterns and replacing them with alternate ones.

CBT therapists help patients to identify depressed thought patterns. The therapist may then encourage the patient to question these depressed thought patterns and recognise them as unhelpful and not representative of reality. The patient is then encouraged to replace these irrational and unhelpful thoughts with more accurate and helpful thoughts. Replacing the depressed thoughts with more helpful thoughts affects the patient’s mood, which in turn affects the patient’s behaviour.

There is often also a behavioural component to CBT. For example, therapy may involve scheduled activities, keeping a diary of thoughts, etc.

Albert Ellis developed a form of CBT based on his ABC model, known as rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT).

AO3 evaluation points: Cognitive treatment of depression

Strengths of cognitive treatment approaches for depression:

- Supporting evidence: Many clinical studies have shown that CBT is effective in treating depression. For example, a meta-analysis by Beltman et al (2010) found that CBT significantly reduces depressive symptoms.

Weaknesses of cognitive treatment approaches for depression:

- Variations between patients: Embling (2002) found that CBT is an effective treatment for depression, but that it is more effective for some personality types than others. For example, individuals high in sociotrophy (i.e. people who strongly desire social acceptance) and with an external locus of control benefit less from CBT than those who are low in sociotrophy and have an internal locus of control. Embling’s study also found that CBT + antidepressant drug therapy is more effective than antidepressants alone.

- Other treatments: There is evidence that biological approaches (e.g. drug therapy such as SSRIs) are equally or potentially more effective for treating depression.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is an anxiety disorder characterised by continuous and repeated undesirable thoughts (obsessions) and uncontrollable behaviours and rituals in response to these thoughts (compulsions).

For example, a person may have an obsessive fixation on germs, which leads them to constantly worry that everything is unclean and dirty. These thoughts may lead to compulsive hand-washing behaviour and rituals as the individual tries to alleviate these obsessive worries.

For example, a person may have an obsessive fixation on germs, which leads them to constantly worry that everything is unclean and dirty. These thoughts may lead to compulsive hand-washing behaviour and rituals as the individual tries to alleviate these obsessive worries.

Characteristics of OCD

Emotional characteristics: High levels of anxiety and stress in response to obsessive thoughts and inability to control compulsive behaviours.

Behavioural characteristics: Continuous repetition of rituals and behaviours in response to obsessive thoughts. Both the obsessive thoughts and the compulsive behaviours get in the way of everyday functioning, disrupting normal activities such as work and social interaction.

Cognitive characteristics: OCD sufferers will continually repeat thoughts to do with their obsession and cognitive biases mean they have difficulty focusing on anything else. Many OCD sufferers are aware their obsessive thoughts are inappropriate and exaggerated but are unable to control them.

Biological approach to OCD

There are many competing and complementary approaches to psychology, including behaviourism, the cognitive approach, and the biological approach. The syllabus focuses on the biological approach to OCD, but other approaches can serve as a means to evaluate this approach.

Biological explanations of OCD

Biological approaches analyse OCD in physiological terms, i.e. as a result of abnormal biological processes. The syllabus lists two different biological explanations of OCD: genetics and neural problems.

The genetic explanation of OCD

Genes are inherited biologically from parents. There is evidence that genes contribute to the development of OCD.

Genes are inherited biologically from parents. There is evidence that genes contribute to the development of OCD.

For example, twin studies suggest a genetic component to OCD. Grootheest et al (2005) conducted a review of more than 70 years of studies on twins and OCD using various methods. One of these methods compared the rates of OCD between identical twins and between non-identical twins. The researchers found it was far more likely for both identical twins to have OCD than for both non-identical twins to have OCD. This supports a genetic role in OCD: Identical twins have identical genetics and so if there is a genetic component to OCD it would make sense that both twins would be similarly prone to developing OCD. With non-identical twins, the different genes could explain why one twin was more likely to develop OCD than the other.

Other studies have used gene mapping to identify correlations between certain genes and OCD. For example, Davis et al (2013) compared the genetic profiles of 1500 OCD sufferers with 5500 non-OCD controls. The researchers’ method (genome-wide complex trait analysis) looked for traits across the entire genome (rather than looking for individual genes) and found the OCD sufferers often shared similar genetic elements that were not present in the non-OCD controls.

The neural explanation of OCD

Another biological mechanism for OCD is neural (i.e. brain and nervous system) abnormalities. These abnormalities may be structural and/or neurochemical.

Brain structures

Brain scans consistently show that OCD sufferers have increased activity in the orbital frontal cortex area of the brain (e.g. Saxena and Rauch (2000)). The orbital frontal cortex is sometimes called the ‘worry circuit’ and is responsible for high-level decision making and thinking (as opposed to low-level primal instincts). When you have an impulse (e.g. to wash your hands when they are dirty), the orbital frontal cortex translates that impulse into action (e.g. washing your hands), and performing that action reduces the impulse. However, with OCD sufferers, it may be that the overactivity of the orbital frontal cortex means these impulses continue even after performing the behaviour, becoming obsessions and compulsions.

Other studies implicate hyperactivity of the basal ganglia in OCD (e.g. Max et al (1995)).

Neurochemistry

Another possible neural explanation of OCD is neurochemistry. For example, several studies (e.g. Hu et al (2006)) suggest that OCD sufferers have lower levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin compared to controls. Some brain scans also suggest OCD sufferers have higher dopamine levels than healthy controls.

AO3 evaluation points: Biological explanation of OCD

Strengths of biological explanations of OCD:

- Supporting evidence: Various physical diseases appear to cause OCD, which supports the neural explanation of OCD. For example, Fallon and Nields (1994) found that OCD occurs in around 40% of patients who catch Lyme disease (a bacterial infection spread by ticks). Johnco et al (2018) found similar results and suggest this may be a consequence of the physiological effects of Lyme disease. Similarly, some studies have found correlations between bacterial throat infections and OCD symptoms1,2,3, while others question these links1,2. The reality may be a combination of both genetic and neural explanations (e.g. bacterial infections may trigger OCD in those who are genetically susceptible) but in any case this supports biological explanations of OCD.

Weaknesses of biological explanations of OCD:

- Other factors: Although there is evidence for a genetic component to OCD, other factors likely play an important role as well. This can be seen in some of Grootheest et al’s (2005) twin studies, where some identical twins did not develop OCD even when their twin did. Overall, the researchers concluded that genetics are between 45% to 65% responsible for OCD in children and between 27% to 47% responsible for OCD in adults. These percentages leave a large role for other factors in the development of OCD, such as environmental influences.

- Alternative explanations: Whereas the biological approach explains obsessive thoughts as caused by abnormal biological processes, the cognitive explanation sees the thoughts themselves as the cause of OCD. For example, a cognitive explanation of obsessive-compulsive cleaning may see the sufferer as having persistent irrational thoughts that focus on anxiety-generating stimuli (e.g. a thought that germs are everywhere and going to infect and kill them). Behaviours that reduce the anxiety associated with these thoughts (e.g. cleaning) become compulsions through operant conditioning.

Biological treatment of OCD

Biological treatment of OCD aims to address the biological mechanisms that cause OCD. The most common biological treatment for OCD is drug therapy.

The most common drugs prescribed for OCD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as Prozac. SSRIs are also known as antidepressants. SSRIs work by increasing serotonin levels, which often reduces obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours to a level that allows the patient to live a more normal life. The effectiveness of SSRIs fits with the neural explanation of OCD that OCD is caused (at least in part) by low serotonin.

If OCD symptoms do not improve with SSRIs, a doctor may also prescribe antipsychotic drugs such as risperidone. One mechanism of risperidone is to reduce dopamine activity, which supports the neural explanation that high dopamine contributes to OCD.

AO3 evaluation points: Biological treatment of OCD

Strengths of biological treatment approaches to OCD:

- Supporting evidence: Multiple studies (e.g. Pigott and Seay (1999) and Soomro et al (2008)) have found SSRIs to reduce OCD symptoms, which suggests that biological treatment approaches to OCD are effective. This efficacy also supports the neurochemical explanation of OCD that low serotonin causes OCD and is not simply correlated with it. However, some studies contradict these findings.

Weaknesses of biological treatment approaches to OCD:

- Side effects: SSRIs may cause side effects including nausea, headaches, sleep disruption, and loss of libido. Some studies (e.g. Juurlink et al (2006)) even suggest SSRIs increase the risk of suicide, though other studies question these findings. The risk of side effects must be weighed against the benefit of reduced OCD symptoms.

- Other treatments: Cognitive-behavioural therapy has been shown to be highly effective at treating OCD. For example, Jonsson and Hougaard (2009) found CBT to be more effective than drug therapy in some studies. Many other studies (e.g. O’Connor et al (1999) and O’Kearney et al (2006)) have found both CBT and drug treatment to be effective in reducing OCD symptoms, but CBT plus drug therapy appears to be the most effective treatment strategy.