Overview – Relationships

This A Level psychology topic looks at the psychology underlying romantic relationships, including:

- Evolutionary explanations of relationships (including differences in male and female reproductive behaviour and partner preferences)

- Factors affecting attraction (including physical attractiveness, self-disclosure, and filter theory)

- Theories of romantic relationships (including social exchange theory, equity theory, Rusbult’s investment model, and Duck’s phase model of relationship breakdown)

- Virtual relationships (including how self-disclosure and the absence of gates make virtual relationships different to face-to-face ones)

- Parasocial relationships (including the absorption-addiction model and the attachment theory explanation)

Evolutionary explanations

Evolution is the process by which species adapt to their environment. Over time, random mutations in genes that are advantageous to the animal become more widespread. This can occur in two ways:

- The mutation increases the animal’s chances of survival (which increases the likelihood the animal will live long enough to reproduce and pass on its genes)

- The mutation increases the animal’s attractiveness to potential mates (which also increases the likelihood the animal will reproduce and pass on its genes)

This second way is known as sexual selection. Evolutionary (socio-biological) explanations of relationships look at the different sexual selection pressures between men and women to provide psychological explanations of relationships.

Anisogamy

Anisogamy refers to the differences between male sex cells (sperm) and female sex cells (ova, or eggs).

These differences between male and female sex cells give rise to different reproductive behaviours:

| Women | Men |

| Finite number of eggs | Continuously produce sperm |

| Approximately 25 years of fertility after puberty | Continuously fertile after puberty even into old age |

| Fewer reproductive opportunities (~300 monthly ovulations over reproductive life) | Greater reproductive opportunities (~100,000,000 sperm per ejaculation) |

| Each child is a significant investment of resources (e.g. the mother has to bear the child for 9 months during pregnancy) | Little investment of resources (i.e. sperm is reproductively ‘cheap’ – it doesn’t take a lot of time or energy to produce) |

| Can produce at most 1 child every 9 months | Can produce up to 3 children per day (in theory!) |

| Optimal strategy: quality over quantity | Optimal strategy: quantity over quality |

Human reproductive behaviour

Human anisogamy means that the optimal breeding strategy differs between men and women (from an evolutionary standpoint of passing on genes). In general, the optimal strategies are:

- Men: Get as many women pregnant as possible and leave them to raise the kids.

- Women: Find a high-quality man who will produce high-quality kids and who will stick around to help raise them.

These two strategies conflict with each other, which results in different reproductive behaviours between men and women.

Male reproductive behaviour

Men can produce children with very little investment of time and resources – they just need to have sex. For a man, getting as many women pregnant as possible produces the most amount of his children, which increases the amount of his genes that survive. There are several strategies males may use to achieve this:

Signs of fertility: Men value signs of youth and beauty in women as these indicate that the woman is fertile. The more fertile a woman is, the more likely she is to fall pregnant with his child.

Signs of fertility: Men value signs of youth and beauty in women as these indicate that the woman is fertile. The more fertile a woman is, the more likely she is to fall pregnant with his child.- Fighting: Males compete with other males for women. For example, some species of deer use their antlers to fight with each other.

- Sneak copulation: Men may secretly cheat on their partners in order to maximise the number of children they have.

- Mate-guarding: Men stay close to their partners to ensure they are not having sex with other males behind their back. This is to prevent getting cuckolded: Where the man ends up raising a child that is not his own.

Female reproductive behaviour

Each child is a significant investment of time and resources for a woman (e.g. she has to carry the baby for 9 months in her womb). This results in a different optimal strategy for ensuring the survival of her genes compared to men. Rather than trying to have as many children as possible, women focus more on ensuring the children they do have are healthy and provided-for. There are several strategies females may use to achieve this:

Signs of resources: Women value signs of resources and wealth as these indicate that the man is able to provide for and raise the child. Sufficient resources (e.g. food and shelter) increase the likelihood that the child will survive and thrive.

Signs of resources: Women value signs of resources and wealth as these indicate that the man is able to provide for and raise the child. Sufficient resources (e.g. food and shelter) increase the likelihood that the child will survive and thrive.- Courtship (dating): Women use courtship to get to know a man and work out whether he would be a suitable partner and father. Courtship has the additional benefit of making the man invest time and effort into the woman (and maybe fall in love with her), which makes the man more likely to stick around after she falls pregnant.

- Sneak copulation: Women may also secretly cheat on their partners as this increases the genetic diversity of their children. The risk of this strategy is the woman getting found out and losing access to her partner’s resources. The potential reward, however, is that she can have children with a genetically desirable ‘stud’ while maintaining access to her partner’s resources.

AO3 evaluation points: Evolutionary explanations of relationships

The characterisations of male and female reproductive behaviours above are extreme generalisations. There are obvious exceptions, e.g. highly monogamous men and highly promiscuous women.

Strengths of evolutionary explanations:

- Evidence supporting evolutionary explanations of human reproductive behaviour: There are multiple studies supporting the existence of the different mating strategies suggested by anisogamy. For example, in Clark and Hatfield (1989) student participants were asked to approach other students on campus and ask questions like: “Would you go to bed with me?”. The vast majority of men said yes when women asked them, whereas zero women said yes when the men asked them.

- Evidence supporting evolutionary explanations of partner preferences: Several studies support the evolutionary explanation of male and female partner preferences. For example, Buss (1989) surveyed 10,000+ adults from all over the world on partner preferences. He found that males valued signs of fertility (i.e. physical attractiveness and youth) more than females and that females valued signs of resources (i.e. financial capacity, ambition) more than males. The male preference for signs of fertility is further supported by Singh (2002), which found that men are attracted to women with waist-to-hip ratios that indicate fertility.

Weaknesses of evolutionary explanations:

- Cannot explain all types of relationships: Evolutionary explanations explain male and female relationships on the basis that they are necessary for reproduction and passing on genes. But this explanation is less able to explain other forms of relationships, such as homosexual couples or couples who choose not to have children.

- Ignores social/cultural factors: Partner preferences differ between cultures and change within cultures over time. For example, Bovet and Raymond (2015) looked at depictions of ideal women from over the centuries up to modern day depictions such as those seen in magazines like Playboy. They found the ideal waist-to-hip ratio of women changed significantly over the centuries. These changes occurred too quickly to be explained evolutionarily, suggesting social and cultural influences also play a role in shaping partner preferences.

Factors affecting attraction

Attraction is a key part of romantic relationships. There are several factors that affect attraction such as physical attractiveness, similarity of attitudes, and self-disclosure.

Self-disclosure

Self-disclosure is when you reveal personal and intimate information about yourself to another person. This creates feelings of intimacy and trust in relationships.

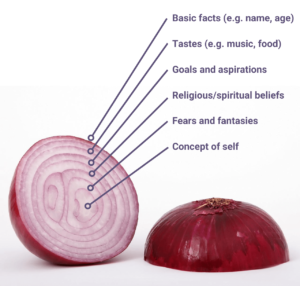

Altman and Taylor’s (1973) social penetration theory describes the process of self-disclosure in relationships. Both the breadth (i.e. the range of topics) and the depth of self-disclosures is important.

Initially, disclosures will cover a narrow range of basic topics in a shallow way – you talk about what you do for a living, your hobbies, etc. As the relationship develops, the breadth of topics and depth of disclosure increases. For example, you talk about more controversial or intimate topics, share painful or embarrassing memories, and maybe reveal some secrets. Altman and Taylor liken this process to peeling away the layers of an onion: You start at the surface and peel away until you get to the core of the person.

Initially, disclosures will cover a narrow range of basic topics in a shallow way – you talk about what you do for a living, your hobbies, etc. As the relationship develops, the breadth of topics and depth of disclosure increases. For example, you talk about more controversial or intimate topics, share painful or embarrassing memories, and maybe reveal some secrets. Altman and Taylor liken this process to peeling away the layers of an onion: You start at the surface and peel away until you get to the core of the person.

Self-disclosure is important in the development of a relationship as it establishes trust and intimacy. However, too much self-disclosure too quickly tends to have the opposite effect: Altman and Taylor found that revealing intimate details too early on (e.g. talking about childhood trauma on a first date) is unattractive.

AO3 evaluation points: Self-disclosure

- Sprecher and Hendrick (2004) found self-disclosure between couples to be strongly correlated with relationship satisfaction, supporting the role of self-disclosure as an important factor in attraction and relationships. However, correlation does not necessarily equal causation – it could be the other way round. For example, it could be that being in a good relationship in the first place causes couples to self-disclose to each other rather than that self-disclosure causes the relationship to be a good one.

- Importance of other factors: Although self-disclosure seems to be a factor in attraction, it is unlikely that self-disclosure alone is enough. Instead, self-disclosure likely interacts with other aspects of attraction, such as physical attractiveness and similarity of attitudes.

- Differences between cultures: Kito (2010) found that for both American and Japanese students self-disclosure was higher in romantic relationships than in friendships, supporting the view that self-disclosure is a universal aspect of romantic attraction. However, Tang et al (2013) found that sexual self-disclosure among US couples was far higher than among Chinese couples, yet relationship satisfaction was equal among both groups. This suggests there may be cultural differences in self-disclosure and attraction.

Physical attractiveness

Physical attractiveness is often the first part of attraction. Getting to know someone’s personality and values takes time, but physical characteristics provide an immediate way to select potential partners.

We covered some evolutionary explanations of physical attractiveness above. According to this explanation, men are attracted to physical characteristics that indicate fertility in females, such as youth and a low waist-to-hip ratio. Although physical attractiveness in partners seems less important to women than men, women are also attracted to physical features that indicate genetic fitness, such as high shoulder-to-hip ratio.

A common physical attribute attractive to both males and females is facial symmetry. Shackelford and Larsen (1997) found that people with symmetrical faces are consistently rated as more attractive than people with asymmetric faces. The evolutionary explanation of this is that symmetry is a reliable indicator of fitness because it requires genetic precision and an environment of abundance during development.

Physical attractiveness often makes us see people as attractive in other ways through the halo effect. The halo effect is a bias where we assume attractive people have attractive personalities too. For example, Dion et al (1972) found that subjects rated physically attractive people as more sociable and more successful in their careers.

Matching hypothesis

Walster et al’s (1966) matching hypothesis says that we choose partners who are similar in physical attractiveness to ourselves. For example, if you rate yourself 7/10, you’ll go for a partner who is also 7/10.

There is an evolutionary element to the matching hypothesis. While it might be desirable to form relationships with the most attractive people, it is not always realistic. If people only went for partners out of their league, they might never find a partner and thus never pass on their genes. So, people assess their own attractiveness and seek out partners who ‘match’ their own level of attractiveness to increase their chances of relationship success.

AO3 evaluation points: Physical attractiveness

- Conflicting evidence on universal standards of female attractiveness: Several studies have found similarities across cultures in what men find physically attractive in women. For example, Cunningham et al (1995) found that White, Asian, and Hispanic males all rated high cheekbones, large eyes, and small noses as attractive in females. Similarly, Singh (2002) found that men find fertile waist-to-hip ratios attractive regardless of culture but Bovet and Raymond (2015) found significant variations in depictions of ideal female waist-to-hip ratios over time.

- Evidence against the matching hypothesis: Walster et al’s own study did not support the matching hypothesis, as the participants preferred partners who were more attractive than them rather than equally attractive. Further evidence against the matching hypothesis is found in Taylor et al (2011), who found that participants using online dating services did not consider their own attractiveness when seeking dates and instead sought partners more attractive than themselves.

- Evidence supporting halo effect: Palmer and Peterson (2015) looked at American election survey data and found that people rated physically attractive people as more knowledgeable and more persuasive, supporting the existence of the halo effect. Further, a meta-analysis from Eagly et al (1991) found subjects were more likely to ascribe positive personality traits to attractive people than unattractive people, but that the halo effect is not as strong as often thought.

Filter theory

Kerckhoff and Davis’ (1962) filter theory says that we select partners by narrowing down the available options using 3 filters:

- Social demography: These are the basic facts that determine whether a relationship is even practical. For example, if someone lives really far away it is likely to decrease the attractiveness of a relationship with them because you will never see them.

- Examples: Same town, same social class, same religion.

- Similarity of attitudes: People tend to be attracted to people with similar values to them. Within the first 18 months of a relationship, partners self-disclose information that enables them to suss out each others’ values and attitudes. If there are few similarities in attitudes, relationships tend not to last beyond 18 months.

- E.g. Both partners believe family is really important.

- Complementarity: When each partner has traits that the other lacks. This makes couples feel like they ‘complete’ each other, and that they fulfil each other’s needs.

- E.g. One partner has a caring nature, the other likes to be cared for.

AO3 evaluation points: Filter theory

Strengths of filter theory:

- Face validity: Many aspects of filter theory seem to be common-sense reasons for attraction. For example, it seems obvious that a person would pursue a relationship with someone nearby so that they can actually meet up with them. Similarly, common-sense might suggest that pursuing a relationship with someone you disagree with on fundamental values and attitudes is not a good idea.

- Evidence supporting filter theory: Winch (1959) found that similarity of attitudes was important for couples in the early stages of a relationship and that complementarity becomes more important in long-term relationships. This supports two of the three filters (similarity of attitudes and complementarity) of filter theory as factors in attraction.

Weaknesses of filter theory:

- Cause or effect: Some research suggests similarity of attitudes is an effect of being in a relationship, rather than a filter through which we select partners. For example, Davis and Rusbult (2001) found that partners’ attitudes change over time to become more aligned (rather than that partners select each other because their attitudes align).

- Questions of temporal validity: The growth of online dating may have reduced the importance of social demography as a filter. For example, people may be more likely to interact with and date people outside their social class or religion.

Theories of romantic relationships

There are three theories of relationships listed on the syllabus: Social exchange theory, equity theory and Rusbult’s investment model. The syllabus also lists Duck’s phase model, which is a theory of relationship breakdown.

Social exchange theory

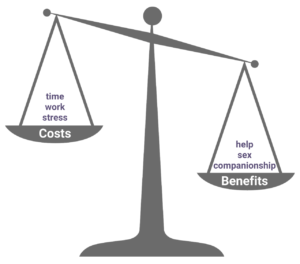

Social exchange theory is the name for a range of theories that view romantic relationships economically in terms of costs vs. benefits.

According to social exchange theories, humans are selfish and so engage in romantic relationships in order to get some benefit. Partners weigh the costs of being in the relationship (e.g. time, effort, loss of freedom, stress) against the benefits (e.g. companionship, help, gifts, sex). If the benefits outweigh the costs, the relationship is ‘profitable’ and there is a desire to maintain it. However, if the costs outweigh the benefits for one of the partners, that partner will break the relationship off as it is no longer profitable to them.

According to social exchange theories, humans are selfish and so engage in romantic relationships in order to get some benefit. Partners weigh the costs of being in the relationship (e.g. time, effort, loss of freedom, stress) against the benefits (e.g. companionship, help, gifts, sex). If the benefits outweigh the costs, the relationship is ‘profitable’ and there is a desire to maintain it. However, if the costs outweigh the benefits for one of the partners, that partner will break the relationship off as it is no longer profitable to them.

In addition to the ‘profitability’ of the current relationship (comparison level), there is the potential profitability of alternative relationships (comparison level for alternatives). If a partner judges an alternative relationship to be more profitable than the current one, they may break off the current relationship – even if it is profitable – to pursue a more profitable alternative relationship.

Thibaut and Kelley (1959) proposed the following model of the various stages of a relationship according to social exchange theory:

- Sampling: Thinking about the costs and benefits of entering into a relationship with someone.

- Bargaining: The relationship is tested out and the partners negotiate costs and benefits to see if the relationship is worth pursuing further.

- Commitment: The relationship is established and the costs and benefits are predictable.

- Institutionalisation: The couple are settled and stable because the norms of the relationship are established.

AO3 evaluation points: Social exchange theory

Strengths of social exchange theory:

- Evidence supporting social exchange theory: Rusbult (1983) conducted a longitudinal study and found that increases in the rewards associated with a relationship led to increased satisfaction with that relationship, supporting social exchange theory. However, Rusbult also found that increases in the costs associated with a relationship did not decrease relationship satisfaction, weakening support for social exchange theory.

- Forms the basis of other theories: Other relationship theories, such as equity theory and Rusbult’s investment model, build on social exchange theory.

Weaknesses of social exchange theory:

- Does not consider other factors: Social exchange theory may miss other factors that are important in relationships. For example, Hatfield et al (1984) found equity to be an important factor in relationship satisfaction – a factor not included in social exchange theory. Similarly, Rusbult (1983) and Lin and Rusbult (1995) found evidence to support investment in a relationship to be an important factor but again this factor is not included in social exchange theory.

- Questions of external validity: Much of the data supporting social exchange theory comes from artificial tasks (e.g. two people are put together for the purposes of the study to see how they act in a game with rewards and costs) and so the findings may not apply to real-life relationships. Further, when studies do use partners in real-life relationships, the results often fail to support social exchange theory.

Equity theory

The equity theory of romantic relationships is about fairness between the partners.

According to equity theory, relationships are successful if each partner equally bears the same amount of costs and benefits. If one partner is benefiting from the relationship more than the other, this is seen as unfair and leads to relationship dissatisfaction on both sides: The underbenefiting partner may feel angry that they are making all this effort and getting little in return, whereas the overbenefiting partner may feel shame and guilt. So, whereas social exchange theory sees people as selfishly trying to maximise their own benefits in a relationship, equity theory sees people as trying to maximise equity (fairness).

Equity theory predicts that inequity (unfairness) is correlated with relationship dissatisfaction.

AO3 evaluation points: Equity theory

Strengths of equity theory:

- Evidence supporting equity theory: Hatfield et al (1984) conducted surveys of newlywed couples to find out the perceived level of equity in the relationship as well as the happiness with and stability of that relationship. They found couples in equitable relationships were more likely to be happy with their relationship and considered their relationship more stable in comparison to couples in inequitable relationships. This supports the prediction of equity theory that equity in relationships is correlated with relationship success and vice-versa.

Weaknesses of equity theory:

- Conflicting evidence: Huseman et al (1987) found that equity is not an important factor in all relationships because some partners are less sensitive to equity than others. This weakens the theory as it provides examples of people who are happy being in inequitable relationships. Further, in a longitudinal study of couples, Berg and McQuinn (1986) found that equity did not increase in many happy relationships (as equity theory would predict) and that factors such as self-disclosure were more important for maintaining a happy relationship than equity.

- Questions of cross-cultural validity: Aumer et al (2007) found different cultures had different attitudes towards the importance of equity in relationships. The researchers found that equity was more important for relationships in individualist cultures than collectivist cultures, and that partners in collectivists cultures were most satisfied in relationships when they were overbenefitting rather than equal.

Rusbult’s investment model

Rusbult’s (1980, 1983) investment model of relationships includes elements of social exchange theory but also considers each partner’s investment in the relationship.

According to Rusbult’s investment model, commitment in a relationship is dependent on three factors:

- Satisfaction level: This is similar to social exchange theory in that it is the weighing of costs vs. benefits of being in the relationship. If benefits outweigh costs and the partner’s needs are being met, then satisfaction is high. Satisfaction increases commitment to the relationship.

- Comparison with alternatives: Also similar to social exchange theory, this is the weighing of the benefits of the current relationship against the benefits of the best possible alternative relationship. If the benefits of the current relationship are greater than alternatives, comparison with alternatives is high. This also increases commitment to the relationship.

- Investment size: The amount of resources – time, money, effort, etc. – invested into the relationship. Investment also covers things like children, shared friends, shared possessions. These things represent an investment in the relationship that would either suffer or be lost if the relationship were to end. High investment in a relationship also increases commitment to that relationship.

AO3 evaluation points: Rusbult's investment model

Strengths of Rusbult’s investment model:

- Evidence supporting Rusbult’s investment model: A meta-analysis of 52 studies conducted by Le and Agnew (2003) found relationship commitment was positively correlated with all 3 elements of Rusbult’s investment model, supporting the theory.

- Cross-cultural validity: Lin and Rusbult (1995) surveyed 155 American students and 130 Taiwanese students. They found feelings of relationship commitment were strongest among couples with high satisfaction, high comparison with alternatives, and high investment, supporting all 3 elements of Rusbult’s investment model. Van Lange et al (1997) found similar results among Dutch students. These findings suggest Rusbult’s investment model has cross-cultural validity, as students from multiple different countries felt greater commitment to their relationships when the 3 elements of Rusbult’s investment model were present.

- Explanatory power: Rusbult’s model can explain various behaviours in relationships. For example, a person may stay in an abusive relationship – even though satisfaction is low – due to the resources invested in that relationship. Another example is cheating: Rusbult’s model can explain a lack of commitment as a result of low satisfaction and low comparison with alternatives.

Weaknesses of Rusbult’s investment model:

- Methodological concerns: Much of the data supporting Rusbult’s investment model comes from self-report techniques such as questionnaires. These methods may not produce valid findings, as participants may give answers that are socially desirable rather than honest. Further, many of the studies supporting Rusbult’s investment model are correlational and so do not establish that the 3 elements of Rusbult’s investment model cause relationship commitment. For example, it could be that being in a committed relationship causes one to invest more into that relationship, rather than the other way round.

Duck’s phase model

Unlike the other theories above, Duck’s phase model is not a model of relationships but a model of relationship breakdown (dissolution).

According to Duck’s phase model, relationship breakdown is not a one-off event but a process that happens in four stages. Each stage marks a ‘threshold’ at which point the perception of the relationship changes. If the partner does not feel there has been enough change, they may cross the threshold of the next stage, increasing the likelihood of a break-up.

| Phase | Threshold | Description |

| Intrapsychic phase | “I can’t stand this anymore” | Thinking you are dissatisfied with the relationship. Focus on partner’s behaviour. Consider the costs of ending the relationship. Weigh up whether to express the dissatisfaction or repress it. |

| Dyadic phase | “I would be justified in withdrawing” | Discussing your dissatisfaction with the relationship with your partner. Confront them about their behaviour. Possible attempts to resolve the problem and repair the relationship. |

| Social phase | “I mean it” | Discussing the relationship with other people outside the relationship. Seek support from friends, family, etc. Negotiate the terms of the break-up with the partner. |

| Grave-dressing phase | “It is now inevitable” | Break up and move on. Come up with stories/explanations of the break-up to tell other people that place blame on the partner and make you look good. |

AO3 evaluation points: Duck's phase model

Strengths of Duck’s phase model of relationship breakdown:

- Face validity: Duck’s phase model has face validity as many people who have been through a relationship break-up will have experienced the various stages described.

- Practical applications: Rollie and Duck (2006) describe how communication at each of the four stages of the model can revert the relationship to a previous stage and avoid progression towards relationship breakdown. This is a practical application of the model that can produce the positive psychological outcome of avoiding relationship breakdown.

Weaknesses of Duck’s phase model of relationship breakdown:

- Does not explain why relationships break down: Duck’s model only describes what the process of relationship dissolution is, but it does not explain why it happens in the first place. A complete psychological model of relationship breakdown would need to include explanations of why the relationship broke down in the first place.

- Exceptions: Although many relationship breakdowns follow Duck’s model, the four stages are not universal. Some relationship breakdowns skip some of the stages and others may go through them in a different order.

Virtual relationships

Virtual relationships are relationships between people who are connected virtually rather than physically. The internet – social media in particular – enables people to form these relationships, which differ from ordinary physical relationships in terms of self-disclosure and the absence of gating.

Self-disclosure in virtual relationships

Differences between virtual and face-to-face communication may lead to greater levels of self-disclosure in virtual relationships than in face-to-face interactions.

Anonymity

Anonymity in virtual relationships may increase self-disclosure. Unlike face-to-face interactions, virtual relationships may be conducted anonymously (e.g. via anonymous forums and burner accounts). This anonymity may increase self-disclosure compared to real-life, as anonymity protects the individual from potential negative social consequences of self-disclosing private or intimate information.

Lack of non-verbal cues

Unlike face-to-face interactions, many forms of virtual communication (e.g. direct messaging, email) do not include cues such as body language and tone of voice. This may lead to increased self-disclosure.

Sproull and Kiesler (1986) proposed that the reduction in non-verbal cues from virtual interactions may make individuals less likely to self-disclose. However, Walther’s (1996) hyperpersonal model suggests the opposite: Non-verbal cues distract from the content of the communication and so removing them in virtual contexts enables the sender to focus more on how they present themselves, enabling superior (‘hyperpersonal’) communication. The hyperpersonal model is further supported by Jiang et al (2010), who found that disclosure and intimacy were higher in text-based virtual interactions than in face-to-face ones.

AO3 evaluation points: Self-disclosure in virtual relationships

- Importance of different virtual contexts: The level of self-disclosure is likely to be very different depending on the context. For example, a post on a public profile linked to your real name and photos (e.g. Instagram) is likely to be curated in order to present the best version of yourself and not disclose embarrassing or intimate information. In contrast, a post to an anonymous forum is likely to involve more self-disclosure because anonymity protects the person from the negative social effects of self-disclosure. This shows that research into self-disclosure in virtual contexts is not one-size-fits-all and must take account of the different virtual contexts.

- Mixture of face-to-face and virtual interactions: Many relationships have both a virtual and face-to-face dimension to them. For example, you might meet up with a romantic partner for a date (face-to-face) and then message them later that evening (virtual). Explanations that assume only a virtual or a face-to-face dimension may lack ecological validity as both virtual and face-to-face interactions are likely to have an impact on self-disclosure.

Absence of gating

Another difference between virtual and face-to-face interactions is the absence of gating. This means that factors that might have prevented a relationship forming in real life (i.e. gates to that relationship) are not present in the virtual context.

McKenna and Bargh (1999) give several examples of potential ‘gates’ that might prevent a person from forming face-to-face relationships. Such examples include facial disfigurement, a stammer, or extreme shyness of social anxiety. However, in the virtual context, these gates do not exist and so a person may be able to form relationships with people who might otherwise reject them because of these reasons.

Similarly, the social demography filter of filter theory is less likely to serve as a gate in virtual relationships. For example, the internet means people can communicate and maintain relationships over large distances, and with people outside their social class or ethnicity.

AO3 evaluation points: Absence of gating

- Positives of absence of gating: The absence of gating means people are able to overcome barriers that might otherwise prevent them from forming close relationships. For example, McKenna (2002) found that people who are socially anxious in face-to-face settings are better able to express their true selves online, leading to close relationships online. This is further supported by Baker and Oswald (2010), who found that among highly shy people Facebook use was correlated with higher friendship quality. This suggests that shy people are able to use social networks to overcome their shyness, which might otherwise have served as a gate in face-to-face encounters.

- Negatives of absence of gating: However, the absence of gates in virtual settings means people can lie about themselves or create fake personas in order to deceive people into relationships (catfishing).

Parasocial relationships

Parasocial relationships are one-sided relationships where a person gets attached to someone they don’t know in real life. For example, someone might engage in a parasocial relationship with a celebrity or social media star.

McCutcheon et al (2002) devised the celebrity attitude scale, which is a questionnaire designed to identify parasocial relationships. Maltby et al (2006) identified three levels of parasocial relationship using this scale:

- Entertainment-social: The least extreme form of parasocial relationship. The person sees the celebrity as a source of entertainment and something to discuss socially.

- E.g. “Reading the news about celebrity X is fun.”

- Intense-personal: More intense. The person is personally invested in the celebrity’s life and may have obsessive thoughts about them.

- E.g. “If some gave me £1000, I would spend it on a personal possession used by celebrity X.”

- Borderline-pathological: The most extreme form of parasocial relationship. The person has delusional fantasies about a celebrity and may exhibit irrational behaviour that prevents them living a normal life.

- E.g. “Celebrity X is my soulmate, I’m going to marry them.”

The syllabus lists two explanations of parasocial relationships: The absorption-addiction model and the attachment theory explanation.

Absorption-addiction model

McCutcheon et al (2002) proposed the absorption-addiction model of parasocial relationships. According to this model, people engage in parasocial relationships to compensate for deficiencies in their lives.

For example, a person whose life is boring may follow a celebrity’s life in order to ‘absorb‘ some of the fun they experience. Or similarly, a person who feels unsuccessful in their own life may follow a famous person’s life and absorb the feeling of their success.

However, the person may become addicted to these vicarious feelings. When this happens, the person may need to increase the ‘dose’ in a manner similar to physical addiction in order to get the same positive feelings as before. This can lead to the irrational behaviour and delusional fantasies typical of the borderline-pathological level of parasocial relationship.

AO3 evaluation points: Absorption-addiction model of parasocial relationships

- Practical applications: Research into the absorption-addiction model has found that teenagers are particularly likely to form parasocial relationships and that stressful life events (e.g. death of a loved one) can trigger these relationships to become more intense (e.g. the borderline-pathological level). These observations can be used to treat and provide support for those most at-risk of developing dangerous parasocial relationships.

- Methodological concerns: Much of the research into parasocial relationships uses self-report techniques such as questionnaires. These methods may not produce valid findings, as participants may give answers that are socially desirable rather than honest. For example, someone who has thoughts about stalking a celebrity may be embarrassed to admit so in a questionnaire.

Attachment theory

An alternative explanation of parasocial relationships is attachment theory. Whereas the absorption-addiction model explains parasocial relationships as a way to compensate for deficiencies in one’s life, attachment theory explains parasocial relationships as a consequence of issues in early attachment.

If you remember from the attachment topic, Ainsworth identified three infant attachment styles: Secure, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-resistant. According to the attachment explanation of parasocial relationships, individuals with insecure-resistant attachment styles in infancy are most likely to engage in parasocial relationships when they grow up. The reasoning behind this is that insecure-resistant infants still desire to form emotional connections (unlike insecure-avoidant infants) but do not want to risk the possibility of rejection that comes with ordinary social relationships. Parasocial relationships thus provide a way for people with insecure-resistant attachment styles to experience the positive emotions of a relationship without the risk of rejection that comes with typical social relationships.

AO3 evaluation points: Attachment theory of parasocial relationships

- Evidence against the attachment explanation: McCutcheon et al (2006) measured attraction to celebrities and attachment styles in 299 students. Although they found that students with insecure attachment styles were more likely to condone stalking and obsessive behaviours, they found no correlation between insecure attachment styles and attraction to celebrities. This contradicts the prediction of attachment theory that those with insecure attachment styles (particularly insecure-resistant) are more likely to form parasocial relationships.

- Methodological concerns: Much of the research into parasocial relationships uses self-report techniques such as questionnaires. These methods may not produce valid findings, as participants may give answers that are socially desirable rather than honest. For example, someone who has thoughts about stalking a celebrity may be embarrassed to admit so in a questionnaire.

<<<Issues and debates

Schizophrenia>>>

or:

Eating behaviour>>>

or: